By Richard DeLuca

As the potential of the steam engine became apparent in the late 18th century, men looked for ways to apply steam power to overland transportation. In Connecticut, Apollos Kinsley used a steam engine of his own design to power a makeshift steam-wagon along Main Street in Hartford in 1797. But the weight of early steam engines, their constant need for water, and the rutted roads of the day presented severe obstacles to steam-powered vehicles. Ultimately, it was the perfection of the steam locomotive, and the low rolling friction of running metal wheels over metal rails, that made steam-powered transportation on land possible and unleashed the full power of the Industrial Revolution.

Connecticut chartered its first railroads in 1832, and by the end of the 19th century about two dozen railroad corporations had built approximately 1,000 miles of main line track within the state. At first, construction took place in the state’s well-traveled north-south river valleys, where grades were flat and stream crossings few. The construction of east-west roads followed. These were more difficult to construct because they passed across the state’s hilly uplands, and so, they were often built in smaller increments.

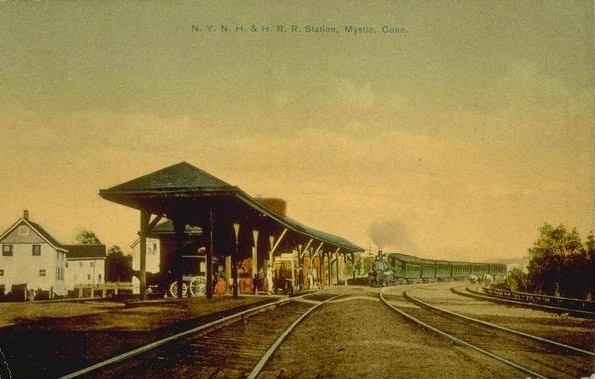

The N.Y. N.H. & H. R.R. Station in Mystic, early 1900s – Mystic Seaport and Connecticut History Illustrated

The most important of these east-west railroads was the New York & New Haven, completed from New York City to New Haven in 1848. Together with the Hartford & New Haven Railroad from Hartford to Springfield and the Boston & Albany Railroad in Massachusetts, the New York & New Haven created the first all-rail route between New York and Boston, along the path of the Upper Post Road. Other New York-to-Boston routes followed, including a shoreline rail through New London and Providence and the famous Air Line route that ran diagonally across eastern Connecticut from New Haven through Middletown and Willimantic.

Perils of Early Railroad Travel

As with many new technologies, the early railroads were primitive compared with what was to follow. Locomotives were designed without enclosed cabs for engineer and crew, and rail cars were simply stagecoach bodies mounted on flanged wheels, their brakes operated from the top of each car by a brakeman using a long, stagecoach-like lever.

Where companies could not afford wrought iron rails, which in the beginning had to be purchased in England, trains ran instead on wooden rails covered with a thin strap of iron. The weight of the train in operation would often cause the iron straps to separate at the joints and curl up into dangerous pieces of raised metal called “snakeheads,” which could pierce railroad car floors and harm passengers. As late as 1844, this condition still existed along the Housatonic Railroad in western Connecticut as several passengers noted in dismay to the Danbury Times on July 3:

… within about three hundred paces of the depot at Newtown, the car in which we were seated was thrown off the track with great violence, and it was only through the interposition of a merciful Providence that we escaped without the loss of life. The railroad is in a most dangerous condition and we counted in a distance of sixty rods over fifty “snake heads” from one to three inches high.

Detail of Locomotive number 14 with workers from the Central New England Railway Co., 1906 – University of Connecticut Libraries, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center and Connecticut History Illustrated

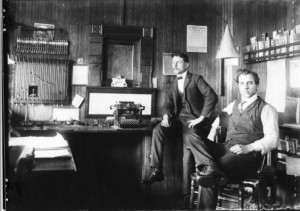

Workers in the Berlin depot office, 1900s – Berlin-Peck Library and the Treasures of Connecticut Libraries

Railroad Conditions Improve

As passenger and freight traffic increased, and revenues were spent improving existing roads, railroad technology dramatically improved. Locomotives became more powerful, rail cars larger, and lines were rebuilt using iron rails. Also, Connecticut created a General Railroad Commission in 1853 to monitor the operations of all railroads in the state, which helped to reduce the number of train accidents. By the time of the Civil War, rail travel in Connecticut had become generally safe, convenient, and reliable.

Because railroad construction required numerous water crossings, bridge building transformed during the railroad decades from a trial-and-error craft into an engineering profession. Many wooden railroad bridges were built as covered spans to increase their useful lives. One of the more unusual was to be seen in Fair Haven, where trains on the Shore Line Railroad crossed the Quinnipiac River on top of a long covered span whose truss was built beneath the tracks. Later, as locomotives became heavier and spans longer, many railroad bridges were built of iron.

Connecticut’s 19th-century rail network also included two notable ferries as an integral part of the Shore Line route from New Haven to New London: one across the Connecticut River from Old Saybrook to Lyme and another across the Thames River from Groton to New London. The two ferry vessels were steam-powered and specifically built to carry rail cars. Once the cars had been loaded aboard, the locomotive remained behind, while another engine stood ready to remove the cars from the ferry on the opposite shore. An iron drawbridge replaced the last of the two ferries, the one that crossed the Thames River, in 1889, by which time Connecticut’s railroad network was essentially complete.

Richard DeLuca is the author of Post Roads & Iron Horses: Transportation in Connecticut from Colonial Times to the Age of Steam, published by Wesleyan University Press, 2011.