By Paige Durgin for Connecticut Explored

County government operated in Connecticut in one form or another for nearly 300 years before the state abolished it in 1960. According to the National Association of Counties, New England states such as Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Massachusetts have not followed the rest of the nation in embracing county government; Vermont’s county system is quite weak, and Massachusetts has in the past 10 to 15 years done away with 7 of its counties. Today, the counties in Rhode Island and Connecticut serve no purpose other than to delineate geographical regions. By the time the state eliminated county government, its major function was to operate jails. The counties’ other responsibilities included maintenance of courthouse buildings, inspection of weights and measures, adjustment of road disputes, administration of certain trust funds (such as cemetery trust funds), appropriation of funds for agricultural extension services, and fighting forest fires. Perhaps the last vestige of county government in Connecticut was the elected office of county high sheriff, which was abolished by constitutional referendum in 2000. The institution of county government may be long gone, but its legacy lives on in the form of courthouse buildings such as the strikingly beautiful Norwich County Courthouse (now Norwich City Hall) and the Windham Courthouse and town hall.

County Government in Connecticut

In May 1666, the Connecticut Colony adopted county government and established four counties: Fairfield, Hartford, New Haven, and New London. By 1785, Windham, Litchfield, Middlesex, and Tolland completed the state’s county system. According to Rosaline Levenson in County Government in Connecticut: Its History and Demise, the General Court, later known as the General Assembly, believed subdividing the state would help by shortening distances people had to travel to conduct business with the colony and by allowing jails and courts to operate with greater efficiency. Meeting twice a year, the county governments operated jails and courts (which handled probate and minor civil suits and criminal cases only; the state court handled more complicated and serious cases), gave out liquor licenses, and dealt with highway and boundary disagreements between towns. County courts were abolished by 1855, and the state assumed all legal duties. Thereafter, the county was only responsible for providing space for the state courts to operate. Henry J. Faeth, in The Connecticut County, notes that in the early 1880s counties also became responsible for the care and protection of neglected or abused children. The counties were authorized to levy taxes to fund their operations. At the turn of the 20th century, the power of the county government system was at its peak, according to Levenson. By the mid-20th century, however, the state had taken over most official functions, leaving little need for county government. Public Act 152 abolished county government in Connecticut on October 1, 1960.

Norwich County Courthouse and City Hall

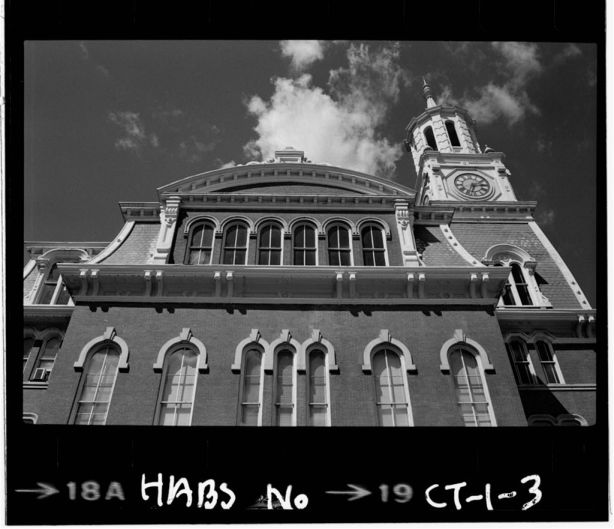

On April 24, 1865, inhabitants of New London County met to talk about where to rebuild their courthouse after the old one burned down earlier that month. It was important to the people of Norwich to erect a building that would function as both a town hall and courthouse—and that symbolized the town’s pride as the seat of an independent, fully functioning Connecticut county. The Connecticut General Assembly granted New London County and the Town of Norwich permission to combine resources and begin construction in 1869. The architectural firm of Burdick and Arnold of Norwich designed the Second Empire courthouse and local contractor John W. Murphy built it. The basement story is granite block, and the main body is made of pressed brick adorned with granite trim. The building housed the jail (in the basement), the police department, and the police court. The superior court, town hall offices, sheriff’s office, and library were on the second floor. At its completion and including its magnificent clock tower, the courthouse stood 87 feet tall. The courthouse was completed in late 1873 at a cost of $315,000, which according to The Norwich Weekly Courier was a “staggering” sum. Within 25 years, the court facilities were considered inadequate, and an addition was finished in 1909.

Windham Courthouse and Town Hall

Willimantic grew rapidly after the Civil War. Early on, the town, which served as county seat, was more concerned with fulfilling the county’s basic needs than with building a town hall, according to the Willimantic Chronicle. When Willimantic became a city in 1893, however, desire to construct a building in the city that could serve as a courthouse for Windham County and a town hall grew. A building committee was formed, and several members visited the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893-1894), where they drew inspiration from that city’s advanced architectural styles. Bridgeport native Warren Richard Briggs designed the Connecticut Building at the Chicago fair, and his proposal for Windham’s courthouse was chosen from among nine designs submitted. Briggs infused his design with colonial, classical, and renaissance features.

In April 1895, the United States experienced a major economic depression, which severely affected Willimantic. In that climate, many opposed the construction of a new town hall and combined courthouse. Despite the controversy, Briggs and Irish contractor Jeremiah O’Sullivan moved forward with the project, and construction began on June 12. They fabricated the first story with sandstone from Portland, Connecticut, and granite from Munson, Massachusetts. Inside the building were offices, a police station, police courts, a superior court, a Grand Army of the Republic (Civil War veterans association) hall, and a library. The total cost was $73,000. On September 16, 1896, the courthouse was complete, and at 6 pm, the tower’s clock dial was illuminated for the first time—by electric light! Today, the building serves as Windham’s town hall, and it stands as a prominent historic landmark. In most states, county government continues to thrive. The National Association of Counties’ Web site suggests that Connecticut’s counties never were as strong here as they were elsewhere because, in our early Puritan settlements, all residents were required to live close to the local church. That tradition turned towns into the dominant political structures as church-centered communities grew into larger towns and cities. Of course, New England states, especially Connecticut and Rhode Island, are so small that dividing the state into counties to provide more-local access to government services isn’t as necessary here as in many larger states. Though efforts to regionalize some municipal functions have popped up in Connecticut, there appears to be no political will to revive formal county government.

Paige Durgin, a 2012 graduate of Trinity College, interned with Connecticut Explored in spring of that same year. © Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 10/ No. 4, FALL 2012.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.