By Shirley T. Wajda

Reverend Thomas Robbins may have thought he had seen it all. After all, a decade earlier he, as a Congregational missionary, traveled to the frontier lands of New Connecticut in northeastern Ohio, where he endured torrential summer downpours, deep winter freezes, and a variety of temperamental fevers and chills. That experience—a long three years—broke his health, and he returned to Connecticut to recuperate. Now, in 1816, he lived in East (now South) Windsor, where he enjoyed a comfortable house, an enviable collection of books (which became the core of the Connecticut Historical Society), and the busy schedule of a minister.

As he had done since 1796, Robbins recorded in his diary the weather and, if not the weather, his activities that revealed the weather. In the first days of March 1816, Robbins planted peas. A week later he noted that the day was “quite warm.” Three days later, on March 12, he noted that it was “cold and wet.” It snowed, and two days later the ground was “considerably frozen.” He would not attempt to replant peas until the end of April.

Chauncey Jerome from Captains of Industry by James Parton, 1884

This was the pattern for the rest of 1816, a year in which famine occurred in New England, remembered for years as “the year without a summer,” “eighteen-hundred-and-froze-to-death,” and the “poverty year.” In April, Robbins cleared his asparagus beds, “but the weather is so cold that vegetation does not appear to advance at all.” In May, the fruit trees bloomed, a hopeful sign, but three weeks into the month several great frosts occurred, threatening the fruit and ruining planted crops. Cold winds blew in June, so much so that “most people that are out wear great coats” and “a steady fire is required.” (The clockmaker Chauncey Jerome, then living in Plymouth, wrote years later, “I well remember the 7th of June. While on my way to work, about a mile from home, dressed throughout with thick woolen clothes and an overcoat on, my hands got so cold that I was obliged to lay down my tools and put on a pair of mittens which I had in my pocket.”) On June 9, Robbins observed that “the cold and wind still continue. The last three days have been extraordinary. It is said that there was snow at the northward last Thursday.” Confirmation of that snow appears in a later entry. On June 10, Chauncey Jerome’s wife “brought in some clothes that had been spread on the ground the night before, which were frozen stiff as in winter.”

Snow in the northwestern part of the state and frost in the southeastern part of the state were ruinous. Williams College professor Chester Dewey observed that “the trees on the side of the hills, whose young leaves were killed by the frost, presented for miles the appearance of having been burned or scorched. The same appearance was visible through the country—in parts, at least, of Connecticut—and also, on many parts of Long Island.”

July, August, and September brought a contrary mix of snow, drought, and oppressive heat. On August 22 Robbins arose to find frost on the ground. The next day he observed that “the ground gets no relief from its drought.” On August 24 it was “warm” but “things grow very little.” The next day he and his congregation “had a very moderate and very refreshing rain,” but three days later Robbins noted “this morning there was considerable frost. It is a melancholy time. There was a fast here yesterday on account of the season.”

At the height of harvest season, on September 5, Robbins confided to his diary, “I presume no person living has known so poor a crop of corn in New England, at this season, as now.” By the end of the month frost had killed much of the corn crop. The low temperatures of the summer months of 1816 spelled disaster for Connecticuters. Farmers had little wheat and corn to take to market. Animals had little to eat. Prices for staples such as flour and meat rose for consumers and the drought caused forest fires, filling the skies with smoke.

Volcanoes, Eclipses, and Sunspots

The year 1816 was not the coldest of the “cold years” between 1812 and 1818: 1817’s winter was colder. As far north as Montreal, as far west as Ohio, and as far south as South Carolina, Americans noted unprecedented cold and drought. So, too, did northern Europe. Several American newspapers published a letter from Paris in October 1816: “All accounts agree that in the memory of no man living, has a season been so cold—they observe there has been no summer.”

At the time, individuals pointed to the increasing size and numbers of sunspots (visible to the naked eye), an eclipse of the moon occurring on June 9, and the vast clear-cutting of forests and cultivation of the soil as reasons. The sunspots, many believed, reduced the sun’s rays and cooled the atmosphere. The moon’s eclipse interfered with the moon’s gravitation pull, resulting in changed wind patterns. (The impact of high winds on plants being clearly visible.) Others theorized the diminishment of forests and the constant turning of topsoil allowed the earth’s heat to escape into the atmosphere and caused the cooler weather.

Today, scientists point to volcanic eruptions as the reason for “the year without a summer.” Four volcanoes erupted in these years, but the fifth, Tambora, on Sumbawa, Indonesia, which erupted between April 7 and April 12, 1815, was the largest. Over 10,000 persons died as a result. The sound of the eruption was heard one thousand miles away. The ashes and cinders created darkness for three days for hundreds of miles around the volcano, and the winds carried these ashes and cinders around the earth.

Scientists also confirm that, during increased sunspot activity, the earth’s temperature is reduced. The combination of increased sunspot activity, heightened volcanic activity, and cooler water temperatures (ice on the Great Lakes and in the Atlantic Ocean) in these years combined to create an agricultural disaster, especially in New England and northern Europe.

The Effects of the Disastrous Harvest

The winter chills from 1812 to 1815, 1816’s ruinous harvest, and the end of the War of 1812 combined to cause “Ohio fever” among the hungry and financially straitened in New England. As Connecticut author and publisher Samuel Griswold Goodrich recalled, “Ohio—with its rich soil, its mild climate, its inviting prairies—was opened fully upon the alarmed and anxious vision. As was natural under the circumstances, a sort of stampede took place from cold, desolate, worn-out New England, to this land of promise.” From his office in Hartford he watched wagons and ox-carts and hand-carts piled high with household goods pass through the streets. Although Connecticut was not as hard-hit as the states of northern New England, like its neighboring states, it experienced slower population growth as its citizens headed westward.

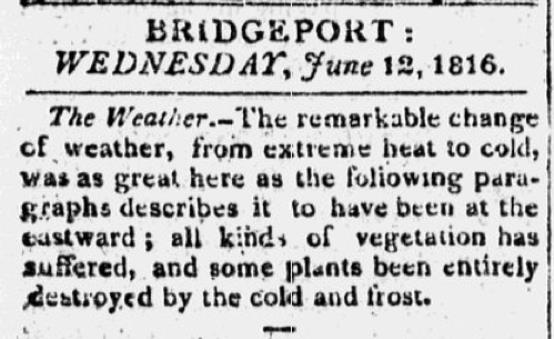

Shirley T. Wajda is the Curator of History at the Michigan State University Museum