By Maya Lopez-Ichikawa

Its lush, open landscape, mini-neighborhoods, and original barns and silos set Wesleyan Hills apart from repetitious blocks of homes that shaped traditional suburbs from the 1940s through the 1970s. Started in 1968, Wesleyan Hills, situated along South Main Street in Middletown, Connecticut, contrasts sharply with the farmland that stood just prior to the creation of its neighborhoods. This story of farmland-to-suburbs reflects the incorporation of open spaces, community, and character as a response to the suburban sprawl that followed World War II.

Suburbanization and the Demand for Open Spaces

Post-WWII suburbanization was a response to an extreme housing shortage, as well as the “great American home ownership” dream of the time. As soldiers returned from the fronts and wartime manufacturing slowed, Americans wanted to find homes outside of overcrowded cities. Additionally, the increased wartime production pulled the country out of the Great Depression and more people had the means to purchase homes.

To meet this demand, enterprising developers like William Levitt applied the principles of mass production to homebuilding. The resulting communities, like Levittown, were tracts of uniform homes on rectangular lots with minimal landscaping. These affordable homes gave the middle class access to the American Dream, though they left some dissatisfied.

Large-scale residential suburban development, Levittown, PA – John William Reps, Cornell University

In the 1950s, a new group of environmental activists emerged and protested the destruction of natural landscapes in the creation of suburbs. Residents of tract communities also began objecting to the poor aesthetics and lack of parks and open landscapes. Scott, a seven-year-old boy from California, even sent a letter to President Kennedy in 1962 pleading for open space: “We have no place to go when we want to go out in the canyon because [they] ar[e] going to build houses so could you set aside some land where we could play?” Open spaces disappeared at an alarming rate as developers rapidly built out the landscape.

The Hill Development Corporation planned Wesleyan Hills in collaboration with Wesleyan University. It responded to the growing dissatisfaction found in repetitious suburbs by setting aside 90 acres of open space on the 288-acre Middletown property. On the southern perimeter, developers left a 10-acre tract of woods and 50 acres of rolling fields. Hill Development built communal parks and smaller “common greens” in neighborhoods as a place to relax, play, and congregate with neighbors.

Emil Hanslin, the development’s planner and landscape designer, saw the social and mental importance of preserving the natural environment within housing developments. He took the unusual approach of hiring a sociologist to help him design a development that was attractive and promoted good health. Hanslin saw the economic advantages of preserving the landscape because of the increasing demand for aesthetic communities with open areas. Wesleyan Hills shifted away from the unappealing monotony of the typical sprawl of that era, and moved towards neighborhoods where parks and landscaping were a central part of the site plan rather than an afterthought.

Cul-de-sac and Community

Mass-produced suburban communities were often laid out on a grid with rectangular lots on rectangular blocks offering homogeneous houses. The authors of Wesleyan Hills’s promotional materials referred to this type of community as “elsewhereville.” The terminology highlighted how Wesleyan Hills differentiated itself from the suburbs of the time by creating cul-de-sacs—dead-end streets with circular turnarounds. This type of layout decreased traffic and made the areas suitable for neighbors to socialize and for children to play. By promoting neighbor relationships, these small, defined communities created a feeling of belonging.

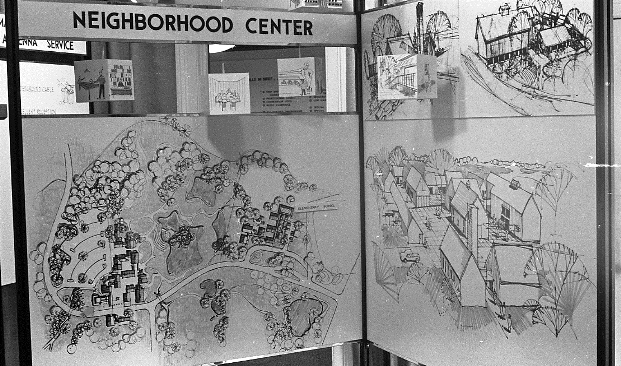

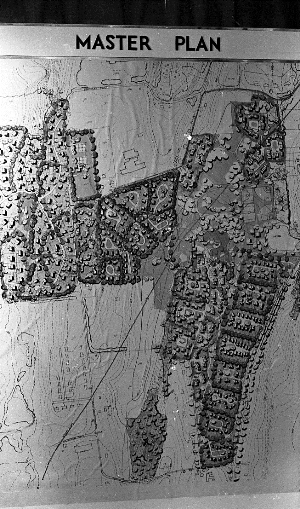

Photograph of the Wesleyan Hills Housing Development Master Plan, Wesleyan Argus ca. 1968-70 – Courtesy of Charles Spurgeon

Mini-neighborhoods were central to the “sense of place” that Emil Hanslin aimed to create. Designers grouped houses of similar architectural style and price into mini-neighborhoods of seven to ten houses in each cul-de-sac. Each mini-neighborhood had a “common green” or “hub,” where children played and neighbors gathered. Dense hedges separated adjacent neighborhoods from each other, which reinforced the feeling of belonging to one’s mini-neighborhood.

Unlike many other suburbs, Wesleyan Hills featured a wide range of housing options intended to accommodate people’s varying needs and budgets. Planners accomplished this through a mix of apartments, condominiums, townhouses, garden apartments, single-family houses, and high-end, custom-built homes. Designers divided neighborhoods by housing style, and even lower-cost apartments benefited from open areas and meeting spaces. Assorted housing options and communal areas created a sense of community and diversity that was lacking in unvaried, mass-produced suburbs.

Looking at the built-out landscape of Wesleyan Hills today, it is clear that the developers took great care to preserve the feel of the land’s agrarian roots. The most notable landmarks are the original barns, silos, and farmhouse. Hill Development refurbished the farmhouse and barns, maintaining the distinctive features, character, and charm of the original structures. James Lash, the first president of Wesleyan Hills, discussed his vision of a town center featuring the existing barns as well as new barn structures. Though this miniature village center never materialized, the barns remain and retain the connection between the community and its rural past.

The barns and farmhouse serve practical uses for events and galleries. The silos, however, are not functional. Developers most likely left these silos in the “hub” of a mini-neighborhood to preserve the character of the land’s agricultural past. Promotional materials reinforce this by depicting a quaint, relaxed suburban development that retained its rural charm.

A Different Kind of Suburb

The story of suburbanization in Wesleyan Hills is one of many in American history. Planned suburbs date back to the time when horse-drawn streetcars made commutes into cities possible. In addition, a wave of suburbs spread in the 1920s after Henry Ford mass-produced automobiles and made owning them a reality for middle-class families. This enabled people to live farther from work and marked a shift to a slower-paced, relaxed suburban lifestyle. After WWII, the great demand for homes sparked the most dramatic suburban growth, producing largely homogeneous developments like Levittown. Wesleyan Hills, though built during this period, stood in stark contrast to characterless suburbs.

Photograph of the Wesleyan Hills Housing Development, Wesleyan Argus ca. 1968-70 – Courtesy of Charles Spurgeon

Wesleyan Hills captures a moment during post-WWII suburbanization when the public resisted monotonous tract homes. Hill Development appealed to this demand by creating a suburb that balanced urban access with rural charm by preserving local agricultural icons. To retain some open space while still providing homes, Hill Development left the forests and created large landscaped areas and parks. The curves of the cul-de-sacs created distinct neighborhoods and the common greens lent themselves to a greater sense of community than the rectangular blocks of traditional suburbs. Wesleyan Hills was a product of its time and reveals a rich story about the open, rural landscape so often romanticized in America.

Maya Lopez-Ichikawa wrote this piece while a freshman at Wesleyan University during the 2014-2015 academic year as a prospective Molecular Biology and Biochemistry major and a resident of California.