By Colin O’Keeffe

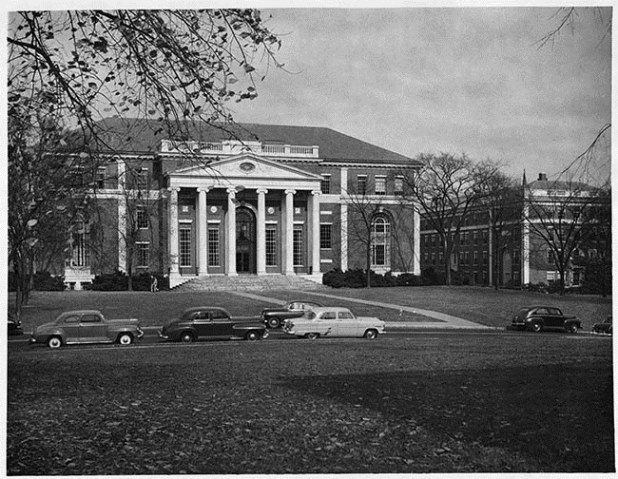

Few buildings in Middletown, Connecticut, are as picturesque as Wesleyan University’s Olin Library. Defined by six monumental pillars, the library’s main entrance, facing Church Street, beckons students and Middletown residents to its front doors. Around back, on the building’s northern side, large glass windows provide an expansive view of Wesleyan’s Denison Terrace and Andrus Field. The history of the university’s library system includes three different locations, two renovations to the current Olin structure, and a debate that reveals how values associated with the environment in the early 1900s helped shape the campus’s development.

Library First Housed in South College, then Rich Hall

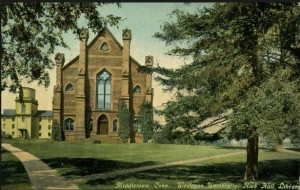

Since Wesleyan’s inception in 1831, the school has always designated a location to hold its book collection. For the first 37 years, this location was simply a room in the building known as the Lyceum (present-day South College). The Lyceum was one structure in a line of buildings, known as College Row, which faced High Street looking eastward toward downtown Middletown and the Connecticut River. As the college expanded and its faculty increased, it constructed Rich Hall (now the Patricelli ‘92 Theater) in 1868 for the exclusive purpose of housing its growing collection of 17,000 volumes. Wesleyan chose to construct this new building in line with College Row so that the courtyard of open grass between the buildings and High Street would be preserved.

The construction of Rich Hall was well received by the Wesleyan community not only because a new library building was needed but also because its location minimized changes to the campus landscape. At this point in time, the core campus of Wesleyan consisted of the buildings on College Row, a few on the opposite side of High Street, and the space between. The open space in front of College Row was complemented by untouched acres behind the buildings, creating a sense of closeness to nature that many at Wesleyan saw as conducive to scholarship and the education of students.

Architect Henry Bacon Designs Campus Expansion and New Library

By 1913, Rich Hall proved too small for Wesleyan’s burgeoning collection, which now totaled some 93,000 volumes. This increase paralleled rising student enrollments. Talk of expansion began anew. By this time, residential properties lined the east, north, and south boundaries of the College Row-High Street rectangle. The only logical direction in which to expand was to the west. Understanding these concerns, the Board of Trustees commissioned architect Henry Bacon to design a full campus expansion, including a new library.

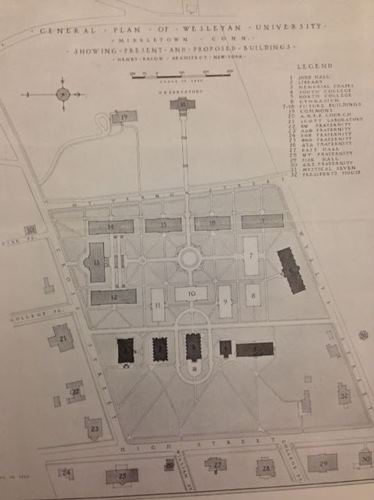

Above is the proposed campus expansion plan by Henry Bacon from 1913. The buildings colored dark grey (College Row) were present before the plan began to be implemented. Central Plan of Wesleyan University from November 10, 1913 – Campus Planning Vertical Files, Special Collections and Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University

Bacon envisioned his 1913 design as a rectangle of separate, unique buildings situated to the west of the existing campus structures. The new library appears as number 13 on his “Central Plan of Wesleyan University” dated November 10, 1913 and shown here.

Bacon, who would later earn national recognition as the architect of the Lincoln Memorial, had some experience with the Wesleyan campus; he had earlier designed the house of the Eclectic Society, a co-ed fraternity founded at Wesleyan. Bacon’s expansion plan for Wesleyan extended beyond designing the buildings; it considered how the land around them would be configured as well. In Bacon’s time nature and unaltered spaces represented creative thought and were believed to help foster an open-mindedness suited to learning. This ideal clashed, however, with the need to expand Wesleyan’s facilities—and the fact that the area behind College Row was the only plausible location for new buildings. To accommodate these conflicting needs, Bacon’s plan not only added the necessary buildings it also used them as a boundary around an open, or green, area.

Wesleyan Growth Sparks Debate

Once published, the plan met with criticism. Despite Bacon’s efforts, many members of the Wesleyan community argued that he and the trustees had not properly balanced the need to preserve open, unused land with the need to expand. The proposed construction would more than triple the size of the campus. It would also shift the campus center from the front-facing side of College Row on High Street to the new cluster of buildings behind it. Much of the controversy stemmed from a desire on the part of many to keep the land behind College Row, extending up to Foss Hill, free of man-made structures.

The fact that the proposed buildings essentially “walled off” the center of the new campus from Church Street (then called Cross Street), Wyllys Avenue, and the residential neighborhoods beyond them also caused concern. It is apparent from recorded complaints that Wesleyan community members not only wanted open space, but they also wanted their campus to open onto, and be integrated with, the Middletown community. It is unclear whether Bacon disagreed with such views or felt that using the buildings as a rectangular boundary to preserve open space at the proposed heart of the re-designed campus outweighed other considerations.

Wesleyan alumnus Rory Jones (class of 1901) was among those who expressed dissatisfaction. In a letter to Wesleyan officials, he argued that the buildings encroached upon Andrus Field and the Indian Hill cemetery and that the plan had neither the spirit nor understanding of “streets or open space.” The complaints inspired by Bacon’s plan confirm environmental historian William Cronon’s argument that land preservation is about more than the physical environment; it is also about the human values that are attributed to, and become ingrained in, the landscape. The proposed transformation of the campus, with its loss of open land and access, represented, according to early 19th-century values, a move that would threaten the intellectual and creative presence Wesleyan had established due, in part, to its relatively unspoiled setting.

Despite these concerns, the Board of Trustees proceeded. By 1916 Clark Hall, located between Andrus Field and Church Street, as well as the Van Vleck Observatory atop Foss Hill were built. Although Bacon’s original plan was never fully implemented, additional structures were later built on the north end of the rectangle in rough accordance with his designs.

McKim, Mead and White Steps in to Complete Olin Library

The largest, most eye-catching—and most environmentally disruptive—of all the proposed buildings eventually constructed was Olin Library. By 1923 Bacon’s plans for the library’s design were underway but he died in 1924. The firm McKim, Mead & White took over the project and completed construction in 1927. Recognizing the likelihood that the library’s collections would continue to grow, McKim, Mead & White designed the back, or north-end, wall of thinner, unornamented materials—in essence treating it as a temporary wall that could be more easily altered to accommodate future expansion.

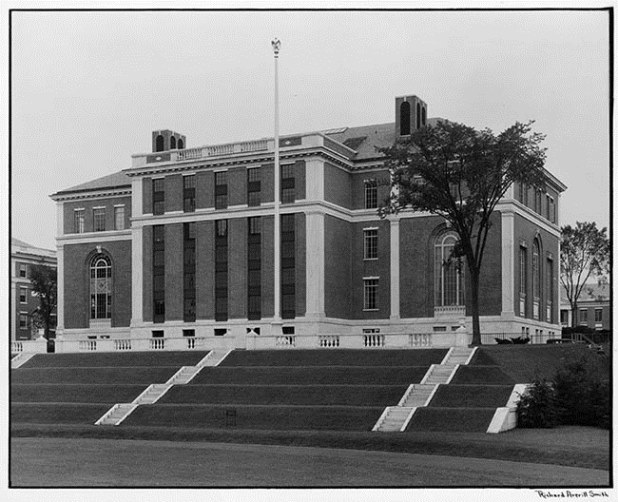

Olin Memorial Library taken from the Hall Laboratory – Wesleyan University Library, Special Collections & Archives

Once built, Olin, along with the buildings on either side of it, created precisely the kind of visual and physical barrier between Church Street and Andrus Field that opponents of Bacon’s plan had lobbied against. However, the town of Middletown and the university did agree to one change that retrieved some of the lost open space and lessened the blockade effect. In 1929, the path of Church Street was shifted diagonally to the South, forming an open courtyard in front of the library for the planting of grass and trees.

The firm’s forethought proved correct when the Board of Trustees opted in 1938 to build on the library’s northern end in order to make room for still-growing number of volumes. Furthermore, by 1984, a second addition was underway which surrounded the 1938 extension. This new northern face of the building, and the one present today, curves outward with seven arched windows overlooking Andrus Field. Compared to the arguments over Bacon’s plan, both renovations went over smoothly within the Wesleyan community. Today, Olin Library, which is also home to Wesleyan’s Special Collections & Archives, stands as more than a symbol of learned academia. Its design, location, and history remind us of how attitudes toward the environment have shaped the man-made structures around us.

Colin O’Keeffe, a freshman at Wesleyan University during the 2013-2014 academic year, is an Economics major and a resident of New Hampshire.