By Diana Dominguez

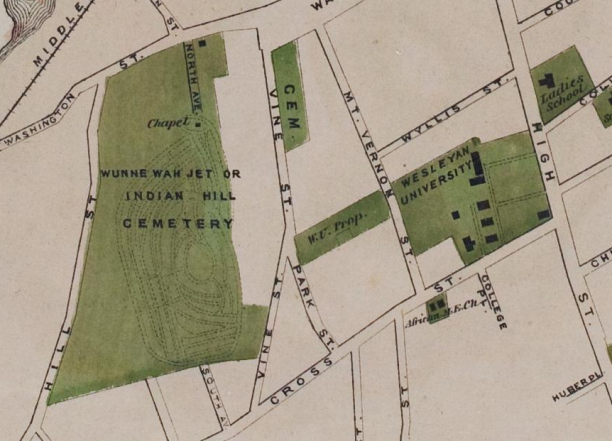

Many names originally given to the land by indigenous peoples are no longer prevalent. Historians often attribute this to the lack of common language between early settlers and Native Americans that resulted in difficulty pronouncing, translating, and remembering names. Evolving views towards indigenous cultures during the 19th century, however, brought about a revival in Native American name usage—a practice supposedly initiated out of respect for the Native American way of life. The Indian Hill Cemetery, in Middletown, Connecticut, provides insight into the culture and ideals behind these naming practices.

Did Americans really seek to commemorate indigenous peoples? What can the founding documents of Indian Hill Cemetery tell us about late 19th-century American views on Native Americans and the use of indigenous names? Understanding the motives behind these choices provides a deeper understanding of common views important to the rural cemetery movement in America. It can be argued that the founders of Indian Hill Cemetery merely sought to promote the cemetery by portraying Middletown’s interactions with Native Americans as friendly—thereby separating themselves from a history that often portrayed whites in troubling and unflattering terms.

The Chapel at Indian Hill Cemetery – Indian Hill Cemetery Association

Romanticizing the Past

The rural cemetery movement emerged from a desire to go back to a time when nature dominated the landscape and indigenous peoples occupied the land. It associated Native American culture with innocence, simplicity, and an intimate relationship with the environment. This movement centered around the idea of constructing cemeteries where both the dead and the living resided—places where death met beauty and nature. Consequently, designers began to surround cemeteries with pleasant visuals such as flowers and nature-themed graphics (images usually associated with peace and tranquility) that invoked a desire for, and romanticizing of, the past.

The Indian Hill Cemetery dedication on September 30, 1850, emphasized popular ideals of the time, glorifying romanticized landscapes and Native American features prevalent in earlier times. The keynote speaker, Reverend Frederic J. Goodwin, invoked the indigenous past, and linked it to American life at the time. He drew upon the “red man of the forest[’s]” choice to stay on the land and his belief that the cemetery was previously a Native American burial ground. He drew parallels between indigenous peoples and Americans by stating that given the choice, Americans would pick the same location to lay their loved ones to rest as the indigenous peoples had, and that whites ultimately seemed destined to suffer the same fate as Native Americans, “the people who perished.”

Eliminating Cultural Differences

Attempts by Indian Hill Cemetery’s founders to separate themselves from narratives of Native American-white hostility come through in the Articles of Association booklet used at Indian Hill Cemetery’s dedication. It featured a list of Native American proprietors that included names of indigenous peoples along with their special roles or duties. By referring to Native American leaders as “proprietors,” Indian Hill Cemetery founders stripped away obvious distinctions between Native Americans and whites. (Many Native Americans, however, did not traditionally classify themselves as property owners.) The indigenous names are also translated to common Anglicized names: for example, Sassepequin to James, or Muckchese to Jacob. The adding of name translations takes away from indigenous identity and merges it with the white, American identity of the cemetery’s founders.

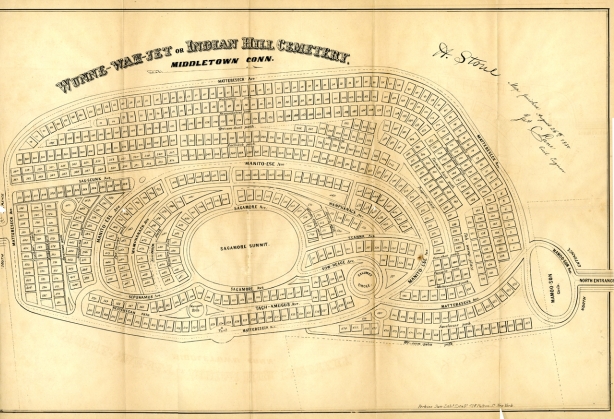

Map of Indian Hill Cemetery, 1850, Special Collections and Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University

In addition, Indian Hill Cemetery documents tell a story that avoids depictions of hostility between Native Americans and whites. Out of respect for indigenous peoples, the cemetery’s founders named pathways and avenues after the “Indian Proprietors.” Most names chosen belonged to Native Americans of important rank, such as Sow-Heage, known as the Great Sachem, or chief; his son Sau-Seunk, who was the Sachem presiding over the sale of the town; and Manitowese, nephew of Sow-Heage, who gave up the deed of New Haven. By commemorating Native Americans who signed deeds of land transference, they portray peaceful interactions between whites and indigenous peoples in the past.

Promoting a Clean, Uncomplicated History

During this period of the 19th century, when Americans romanticized indigenous cultures, Indian Hill Cemetery’s founders looked to increase their business by portraying the cemetery as a peaceful and harmonious resting place. To do this meant stripping away differences used to forge Native American and white identity. By choosing to eliminate many of the distinctions between whites and indigenous people, these men sought to promote a clean, uncomplicated history, free from conflict.

Diana Dominguez wrote this as a freshman at Wesleyan University during the 2014-2015 academic year while also a prospective Neuroscience and Behavior and Dance double major on the Pre-Med track, and a resident of New York City, New York.