By Nancy Finlay

They called it the “White Plague.” It was one of the leading causes of death in the United States during the early years of the 20th century. Few communities were untouched by it, and fear of contagion was widespread. Although, like cancer, tuberculosis affected different parts of the human body, the most frequent and most familiar form attacked the lungs and became known as “consumption.” This form of the disease produced fever, a racking cough, and increasing fatigue as the infection spread and the body consumed itself from within.

Because the progress of the disease was often slow and it was possible to be infected without showing any overt symptoms, many initially believed that tuberculosis (TB) was not contagious. It was only in 1882 that a German doctor, Robert Koch, succeeded in identifying the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis and proving that it caused the disease. Koch developed a vaccine (which he called “tuberculin”) made from an inactive form of the bacterium.

Dr. J. H. Kent of Putnam spent four months in Koch’s laboratory in Berlin and was one of the first to bring tuberculin to the United States. After using it to treat several cases, however, he realized that it was not effective and abandoned its use. Tuberculin subsequently proved to be an effective test for tuberculosis but not the long-sought cure.

Treating Tuberculosis in Connecticut

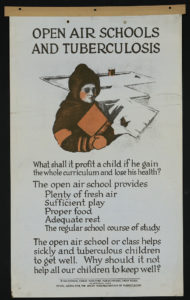

Open Air Schools and Tuberculosis – Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

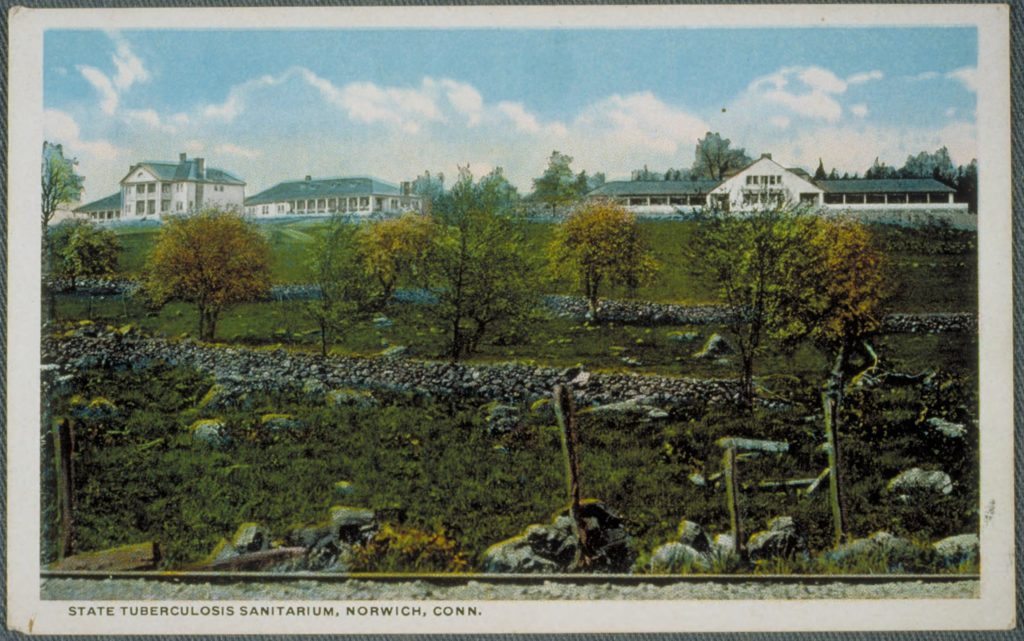

Without a cure, treatment focused on isolating infected people to prevent them from spreading the disease. Wealthy and middle-class sufferers sought relief in warmer or colder climates, such as Florida, the American Southwest, or Switzerland, while the poorer victims relied on a statewide system of sanatoriums. Hartford County Sanatorium in Newington, the New Haven County Sanatorium in Meriden, and the Fairfield County Sanatorium in Shelton were all established in 1910; the New London County Sanatorium in Norwich opened in 1913.

Hartford Hospital operated Wildwood Sanatorium on Cedar Mountain and the New Haven County Anti-Tuberculosis League operated Gaylord Farm Sanatorium in Wallingford. The Seaside Sanatorium in Waterford, a state-run facility for tubercular children, opened in 1934 after years of effort to find a suitable site. In addition, other treatment facilities appeared throughout the state.

Treatment at all of the facilities focused on fresh air and wholesome food. Doctors advised patients to stay outdoors as much as possible. In its 1905 annual report, Gaylord Farms stated that most of its patients slept outdoors all winter.

Other efforts to combat the disease focused on improving living conditions in the slums of Connecticut’s cities and offering “fresh air excursions” to the cities’ children. An outdoor school for children considered at special risk for tuberculosis, such as children of tubercular parents, opened in Hartford in 1909. Officials ordered the slaughter of hundreds of dairy cows that tested positive for tuberculosis in an attempt to prevent the spread of the disease through infected milk. Visiting Nurses Associations appeared in many towns and cities, in part, to help identify cases of tuberculosis and refer them for treatment.

Wildwood Sanatorium, Hartford, Conn. – Hartford Public Library and Connecticut History Illustrated

Beginning in 1907, the sale of Christmas seals supported both the efforts of the National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis and also local charitable organizations such as the Hartford Tuberculosis Society. But despite all efforts, tuberculosis continued to ravage the state and fear of the disease remained widespread. An article that appeared in the Hartford Courant in 1930 described “victims of tuberculosis . . . wandering the streets of Connecticut towns and cities, spreading the germs of their malady and infecting their loved ones at home.”

Streptomycin Changes TB Treatment

Tuberculosis proved immune to the earliest antibiotics, but in the 1940s, streptomycin, a mold that, like penicillin, produced antibacterial by-products, proved effective in halting the disease. Patients improved dramatically within weeks and with continued treatment became free of the bacteria within a year.

With their patients largely cured, most of the sanatoriums closed. Gaylord Farm reinvented itself as a rehabilitation center specializing first in other pulmonary diseases, then in injuries to the brain and spinal cord. Today, it remains one of the finest long-term acute care hospitals in the state.

Tuberculosis also survives. Drug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis have continued to emerge despite the development of newer and stronger antibiotics. TB is still a serious threat in developing nations and to patients with compromised immune systems, and it appears to be on the rise in the general population. It remains one of the top ten causes of death worldwide. Doctors reported 52 cases in Connecticut as recently as 2016.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.