By Rachele Merliss

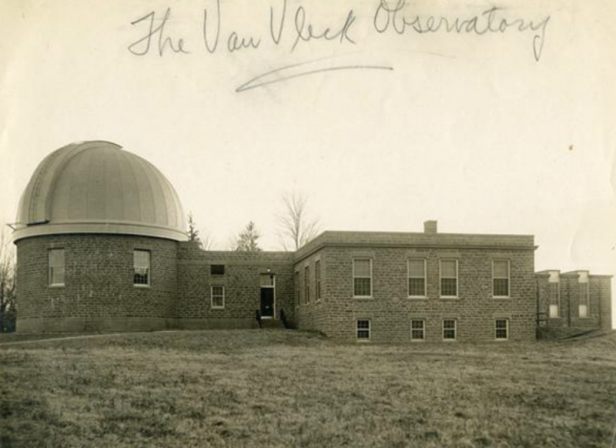

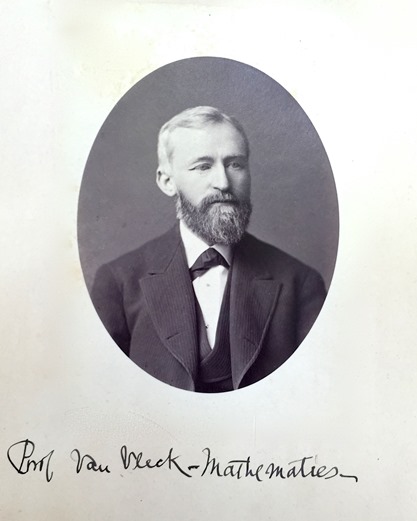

Until 1916, the Wesleyan University observatory was a tower mounted on a dormitory with few instruments and little research capability. Before that, the Middletown, Connecticut, university’s astronomy building was little more than a shed. Professor John Van Vleck, who taught astronomy at Wesleyan for 50 years, believed the university capable of better. He envisioned an observatory with the facilities necessary to make an impact on the world’s understanding of the universe.

John Monroe Van Vleck, American mathematician and astronomer, ca. 1875.

In 1903 Van Vleck’s family donated more than $25,000 to the university for a new observatory and planning began, but Professor Van Vleck passed away before his vision came to life. In his stead, Wesleyan’s president, Stephen H. Olin, entrusted Frederick Slocum, the new astronomy professor, with supervising the observatory’s design. Slocum began a detailed correspondence with Henry Bacon, the architect charged with designing the observatory, to recommend the location, design, and technology of the building.

Slocum proved as determined as Van Vleck to see the Wesleyan observatory contribute valuable research to the scientific community. He knew that it would not be easy, as New England’s cold, wet, and changeable climate is not ideal for astronomical observations. Slocum used a number of means—geographical, architectural, and technological—to overcome the challenges of doing astronomy in the relatively poor observational environment of New England.

Overcoming Connecticut’s Geography

Professor Slocum sought to use local geography to overcome the environmental obstacles to observation. In the 19th century, many of the world’s most successful observatories resided on mountaintops—free from visual obstructions. This need for height was a reflection of the limited technology available at the time. Telescopes did not have the enormous magnifying power they do today, so it was all the more important for an observatory’s location to provide a clear view. This was especially true of New England, where the atmosphere was rarely steady or clear enough for accurate readings. Rainfall, cyclonic storms, and cloud cover often prevented observation.

Wesleyan’s previous observatory relied on its height to grant a good view in these unfavorable conditions. Slocum, however, resolved the problem not with a tall building but with a modest building on a tall hill. Slocum recommended that Bacon place the observatory on the crest of Foss Hill, the highest point on the Wesleyan campus. The advantages of the location were not fleeting. Though Middletown and the Wesleyan campus continued to develop throughout the 20th century, Foss Hill still elevated the observatory above the new buildings.

The Architectural Strategy for Van Vleck

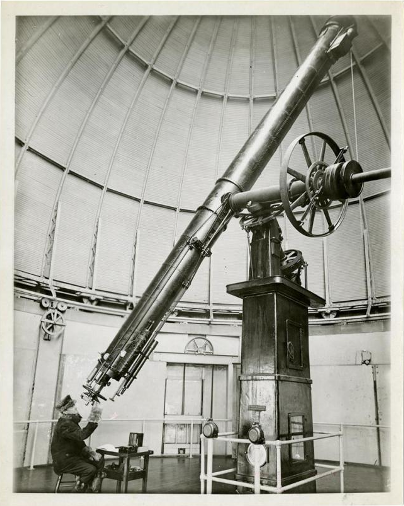

Frederick Slocum sits at the 20-inch refracting telescope around which the observatory dome was designed – Wesleyan University, Olin Library, Special Collections & Archives, Vertical Files Collection, Van Vleck Observatory folder

Having successfully employed the local geography to benefit the observatory, Slocum turned to architectural means to adapt it to New England’s uncertain stargazing climate. The professor looked to observatories in the same climate region as Wesleyan for designs to emulate. He noted that despite the problematic temperature fluctuation, humidity, and cloudiness of the Northeast, the observatories at Harvard and Brown had been highly successful. Slocum attributed a large part of this success to the buildings’ designs. The two observatories each boasted a dome adjoining a flat-roofed building.

Domes were frequently used for observatories because they neutralized the surrounding climate to make visual conditions more favorable. They also improved visibility and allowed airflow that regulated temperature and humidity, keeping instruments safe from the cold, wet New England weather. The velocity of wind must change when it encounters an obstruction, creating layers that distort light, but wind passes by a dome much more easily than it does a wall. A dome can allow visibility of celestial bodies a full magnitude fainter than can be viewed in a flat-roofed building with the same instrument.

But a flat roof is not without its merits. Slocum desired that Wesleyan’s astronomy building have a section of flat roof like the observatories at Brown and Harvard, to allow scientists to step out of the dome for a panoramic view of the heavens. In addition, a rectangular section gave the space necessary for astronomers to analyze the observations made in the dome.

Observatory Technology

The Van Vleck Dome on Foss Hill. Photo by Rachele Merliss, October 2015

Slocum then turned to technology to adapt the Wesleyan observatory to environmental conditions. He determined that the university, constrained by a small budget, faced two options in purchasing instruments—either buying a few small instruments or, instead, use all the money allotted on one enormous telescope. Slocum believed that small instruments did not have the capacity to pierce the thick, murky atmosphere of New England. To afford the mammoth instrument, Slocum and Bacon cut the budget in other areas and asked for more donations. Thanks to these efforts, in May 1914, they were able to afford a telescope with an 18 1/2-inch lens. Due to a mistake from the manufacturers, the lens arrived even bigger than promised, at 20 inches.

Henry Bacon incorporated each of Slocum’s recommendations into the observatory. When workers finished it in 1916, some citizens of Middletown complained that it looked like a beehive and stood out too much from the surrounding landscape. But every aspect of the building was purposeful, planned by Slocum and implemented by Bacon’s design.

In a climate too wet, windy, and changeable to easily produce clear astronomy readings, Professor Frederick Slocum found creative solutions. He used geography, architecture, and technology to adapt to the environmental conditions of the region and period, creating an observatory that, in 1916, brought John Van Vleck’s dream to life. The Van Vleck Observatory continues to do so one hundred years later.

Rachele Merliss authored this piece while a student at Wesleyan University as part of a class project in environmental history.