By Doe Boyle

The first multi-lane, limited-access roadway in Connecticut, the Merritt Parkway, was also one of the first scenic parkways in the nation. Characterized by its landscape design as well as by ornamental Art Deco and Art Moderne bridges, the 37.5-mile parkway improved access to New York City and influenced the development of Fairfield County. It cost $21 million and was the largest public works project in Connecticut at the time of its opening from 1938-1940. The parkway linked to New York’s Hutchinson River Parkway (the “Hutch”) and led developers, as well as day-trippers and commuters, to the Connecticut suburbs.

A Better Transportation Route

By the early 1900s, congestion routinely clogged portions of the Boston Post Road (U.S. Highway 1), which connected the Massachusetts capital to New York City. Connecticut State Highway Commissioner John A. MacDonald proposed a solution: a new parallel route that would begin on the New York State border in Greenwich and end at the Housatonic River on the Stratford-Milford town line. The parallel road, MacDonald argued, would improve traffic flow and increase highway safety. In 1926, the State Highway Department hired consultants to study MacDonald’s idea, and, by the end of the decade, the State Legislature approved a bill that authorized him to plan the highway.

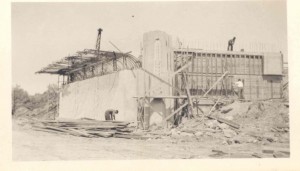

The Darien Road Bridge in New Canaan, Merritt Parkway construction, 1937 – Connecticut State Library, State Archives, RG 069:036, Weld Thayer Chase Collection

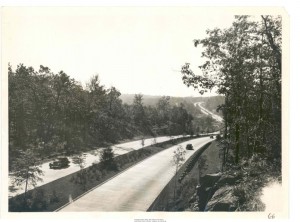

Merritt Parkway looking west toward the Black Rock Turnpike exit in Fairfield, 1934-40 – Connecticut State Library, State Archives, RG 069:036, Weld Thayer Chase Collection

Created during an era when road engineers and landscape architects were designing routes to entice city dwellers into rural areas, the parkway grew out of an idealized philosophy that sought to balance the built environment with the natural landscape. Construction of the “Queen of Parkways,” however, was accompanied by controversy and scandal. Although its construction employed more than 2,000 laborers and met the goals of relieving congestion, preventing accidental loss of life on Route 1, and contributing to Fairfield County’s economic development, the Merritt Parkway did not evolve without problems.

The extension to the Hutchinson River Parkway polarized Fairfield County residents. Wealthy landowners opposed plans that would splice their countryside estates and attract strangers. These landowners and their supporters formed the Fairfield County Planning Association (FCPA) to fight both the proposal of the State Highway Department and the residents and business owners along the Boston Post Road who supported the inland bypass. Led by Republican congressman and Stamford resident Schuyler Merritt, for whom the parkway is named, the planning association argued for a parkway that would maximize the natural features of the landscape and minimize the alterations necessary for construction of a level roadway. Emphasizing recreation over commuting, Merritt lobbied for a parkway that would attract “desirable” residents.

The Parkway’s Problems

From its outset, the parkway encountered financing setbacks, real estate tangles, and land-purchase issues. These problems slowed the project’s progress for years. The State General Assembly proposed a conservative spending doctrine and argued about appropriations. Hopes that New Deal relief agencies, such as the Public Works Administration (PWA) and Works Progress Administration (WPA), might provide needed funds were disappointed. In the meantime, the Fairfield planning association lobbied MacDonald, Governor Wilbur L. Cross, and the General Assembly about the prevention of loss of life on Route 1, the provision of employment for laborers, and the potential for economic development.

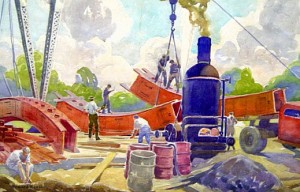

Beginning in 1935 WPA artist Howard Heath created a series of watercolors on the construction of the Merritt Parkway – State Archives, Connecticut State Library

Merritt pressured the General Assembly to allow Fairfield County to issue $15 million in bonds, which would be amortized annually using the highway commission’s funds. The state contributed another $6 million. The federal government added no funds at all. Other provisions reflected planning association concerns: the road would be known as a parkway, not a highway, and commercial vehicles would be prohibited from its roads. Construction began on July 1, 1934—but the controversies had not ended.

Real Estate Scandal

To secure rights of way, McDonald could have used eminent domain; instead, he appointed a state land purchaser, Darien real estate agent G. Leroy Kemp. Because MacDonald kept the parkway’s proposed route a secret, Kemp—charged with acquiring 2,600 acres for parkway rights of way—could share privileged information about desired parcels of land with two real estate contacts, Thomas H. Cooke of Greenwich and Samuel H. Silberman of Stamford. These brokers approached landowners with offers to negotiate sales with the state. In exchange for information from Kemp, the two realtors split their commissions fifty-fifty with Kemp and engineered the deals so that the state paid exorbitant prices—that is, until parkway project engineer Warren Creamer reviewed the purchases. He reported that Kemp’s tactics had inflated the parkway’s cost through sales that were many times over the market value of the assessed properties.

On March 18, 1938, a Grand Jury indicted Kemp, Cooke, and Silberman for conspiracy to divide real estate commissions. The Grand Jury’s final report recommended that the Merritt Parkway Commission be abolished and called for MacDonald’s resignation, which the commissioner submitted on April 29. Governor Cross then appointed Yale professor William J. Cox as the new commissioner.

Parkway Design Brings Beauty to Built Environment

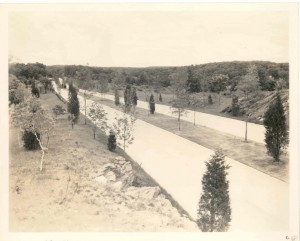

Workmen planting cedars in Stamford, Merritt Parkway landscaping, 1937 – Connecticut State Library, State Archives, RG 069:036, Weld Thayer Chase Collection

The Merritt Parkway’s “Ripple’s Cut,” Greenwich, 1939 – Connecticut State Library, State Archives, RG 069:036, Weld Thayer Chase Collection

Despite these many challenges, not everything about the project was contentious. The beautification of the landscape was a matter upon which all agreed. Engineer for roadside development A. Earl Wood and landscape architect Weld Thayer Chase both admired the approach of 19th-century landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted, who had championed the use of native flora. From 1935 to 1942, Chase planned and supervised the planting of 22,000 trees and 40,000 shrubs. He also protected as many native trees as possible, instructing engineers to create gently graded slopes to reshape ragged construction cuts.

Even more famed than the landscaping were the bridges designed by architect George Dunkelberger, who created 69 unique overpass and underpass bridges. These were built primarily of reinforced concrete or with steel frames and stone fascia (or bands). Constructed with wing walls that integrated with the landscape, the bridges added distinctive visual interest. Despite concerns about their safety, they were highly admired and widely associated with the roadway’s appeal.

Opening Day

On Wednesday, June 29, 1938, in Norwalk, hundreds of spectators watched the opening ceremonies for the parkway’s first 17.5 miles. Governor Cross sheared a white ribbon with a pair of golden scissors in the presence of guests Schuyler Merritt, Attorney General Homer S. Cummings, Public Works Commissioner Hurley, Commissioner Cox, and former Commissioner MacDonald.

After the ceremony, nearly 100 cars drove onto the parkway, led by Cross in the first automobile. Ribbon-cutting ceremonies were repeated in New Canaan, Stamford, and Greenwich and at the New York state line, where representatives from New York met the procession.

Preserving the Parkway

In the 1950s and 1960s, threats came to the original forms of the Merritt Parkway as other new highways, such as the Connecticut Turnpike (Interstate Highway 95), led to traffic increases that funneled into the parkway. In the 1970s, Connecticut built State Routes 8 and 25 to allow commuters and travelers to avoid urban surface streets. Both highways intersected with the Merritt Parkway, so the State Department of Transportation planned two multi-level interchanges that would include widening a five-mile stretch of the roadway. In response, preservationists and concerned citizens formed the Save the Merritt Association, which called for a halt to widening plans and a redesign of the proposed interchanges. In the end, the state added entrance and exit ramps at points where heavy traffic was anticipated, leaving the rest of the parkway unaltered.

Merritt Parkway to New Haven, 1941 – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

In the early 1990s, the transportation department considered plans to increase the roadway to eight lanes—a move that would force the alteration of its famous bridges and artistic landscaping. Local grass-roots and state organizations, including the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation, came to the parkway’s defense. In 1991 and 1993, their efforts placed the Merritt Parkway on the National Register of Historic Places and earned it a designation as a state scenic road. The latter victory ensured that a committee would have to review proposed changes or improvements to the road.

In the mid-1990s, Emil Frankel, commissioner of the State Department of Transportation, created the Merritt Parkway Working Group, which advises the department on matters of preservation and enhancements that allow the parkway to survive as both a major transportation artery and as a cultural and historic resource.

Concerns about the roadway’s safety paved the way for at least one important modernization: In 2006, engineers replaced the original steel-deck Igor I. Sikorsky Memorial Bridge, which spans the Housatonic River. The new bridge, complete with concrete deck and blacktop surface, features a walkway for pedestrians and cyclists, wrought-iron railing, and period lighting. Concrete fenders on its piers protect the bridge from ship collisions.

In the 21st century, the Merritt Parkway Conservancy serves as a public-private partnership that implements the findings of the Merritt Parkway Working Group. A small museum dedicated to the history of the parkway opened in 2006 in Ryder’s Landing Shopping Center in Stratford, not far from the bike-and-pedestrian path near the Sikorsky Bridge. Operated by the parkway conservancy, the Merritt Parkway Museum features archival materials, a video presentation that describes the challenges of the parkway’s construction, and a wall-mounted version of the conservancy guide, which showcases points of interest on this venerable roadway.

Doe Boyle, a Connecticut Office of the Arts Master Teaching Artist of creative and expository writing, is an editor, a widely published freelance writer, and the author of 11 children’s books and 2 travel guides to Connecticut, her home state.