By Herbert F. Janick

The eastern seaboard of the United States—blessed with abundant rainfall, relatively mild climate, and few natural calamities—has been hospitable to a large population. But on occasion nature goes berserk and produces a tragedy. Such was the case on September 21, 1938, when a tropical hurricane, the first since 1815 to visit New England, suddenly veered inland, pulverizing Long Island and cutting a swath across Connecticut. The result was what the Hartford Courant called the “most calamitous day” in the state’s history.

It was hard for Americans, absorbed with the Munich Conference and impending war in Europe, to comprehend fully the enormity of the disaster. It is even more difficult for present generations to appreciate what William Manchester termed “one of the forgotten fragments of American history.” Statistics are cold. Six hundred eighty-two people were killed, and 700 were injured in New England alone. With respect to property, 4,500 homes, 2,600 boats, and 26,000 automobiles were destroyed, and the total cost of property lost amounted to $400 million.

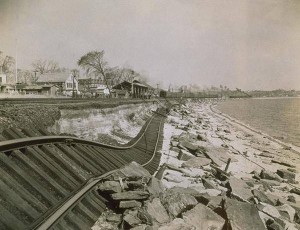

Lighthouse tender Tulip on tracks near dock after the 1938 Hurricane, New London – Archives & Special Collections, University of Connecticut Libraries and Connecticut History Illustrated

The details of the disaster are more graphic. The eastern corner of the Connecticut coastline adjacent to Rhode Island, not buffered by Long Island, was hardest hit. New London was devastated by wind, floods, and fires that raged out of control in the downtown for over seven hours. Ships torn from their moorings slammed around the New London harbor, wrecking wharfs before sinking or beaching themselves. The lighthouse tender Tulip draped its frame across the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad tracks behind the Customs House. When the Port Jefferson-Bridgeport ferry that had spent a harrowing night in Long Island Sound tried to land the next morning in New London, no docks remained. The Shoreline Express, filled with passengers from New York bound for Boston, was marooned outside Stonington on tracks that were underwater. The rest of Connecticut, particularly the Connecticut River Valley, suffered terribly from floods. The river and its tributaries, already swollen by four days of rain, burst their banks. Downtown Hartford was inundated, and WPA (Works Progress Administration) workers built a half-mile dike of sandbags to protect the Colt factory. Tobacco barns were flattened in the valley, and the year’s crop was ruined.

Hurricane of 1938, Niantic – Archives & Special Collections, University of Connecticut Libraries and Connecticut History Illustrated

It is easier to describe what happened that fateful September day than it is to explain why the disaster took place. The hurricane hit at full moon when the tide was its highest. Already powerful, the whirlwind got caught between two high-pressure systems just before it moved inland and instead of dissipating, it became more intense. After almost a week of steady rain, the air over New England was as moist as that over the ocean, a factor that caused the storm to reverse the usual pattern and pick up speed overland. In addition to the natural circumstances, the failure of the Weather Bureau to give any warning of the storm’s potential contributed to the lack of preparation on the part of New England residents. Together the combination of chance and human error produced one of the most destructive hurricane in Connecticut’s history.

By Herbert F. Janick; excerpted from Connecticut History and Culture: an Historical Overview and Resource Guide for Teachers (1985), edited by David Roth.