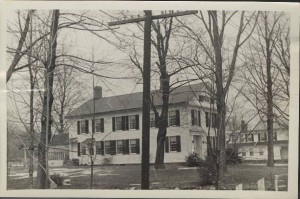

On Marion Avenue in the southwest corner of Southington sits a white clapboard, two-story house decorated in the Greek Revival style. Known as the Levi B. Frost House (or the Asa Barnes Tavern), the home represents over two centuries of Southington history. Appearing twice on the National Register of Historic Places, once as an individual structure and once as a part of the Marion Historic District, the home is significant both architecturally and historically for the insight it provides into early New England history.

Revolutionary War Hero Among Barnes Tavern Guests

Around 1765, Asa Barns began operating a tavern out of his home on the Marion road—a thoroughfare important for connecting Bristol to New Haven. Known as the Barnes Tavern (the “e” in Barnes first appearing in land records in 1825), the inn hosted numerous weary travelers who braved the crude and rocky Connecticut roads. Among these guests was a famous French general who played a vital role in helping the colonies during the Revolutionary War.

Asa Barnes Tavern, Southington c. 1935-1942. – Connecticut State Library, State Archives, WPA Records, Architectural Survey. Used through Public Domain.

On his way to meet George Washington in North Castle, New York, the French general Jean-Baptiste-Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, arrived at what is now “French Hill” near Barns’s tavern on June 26, 1781. Rochambeau used the tavern as his headquarters for 4 days while his troops camped across the street. The following year, on his victorious march from Yorktown, Virginia, back to Rhode Island where he’d first landed, Rochambeau returned to Barnes Tavern on October 27th.

From Inn to Site of Manufacturing Innovation

Asa Barns lived in the house until his death in 1819. The house then went to his son, Philo. Philo was a prosperous land owner whose son, Seth, raced West in search of gold in the 1840s (ultimately dying in a prison camp in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1863) and whose grandson, Edwin, went on to become general manager of the nearby Clark Brothers Bolt Company. Philo leased the house to bolt manufacturing pioneers Micah Rugg and Levi B. Frost.

Frost, a blacksmith who specialized in shoeing oxen and selling farming supplies, eventually purchased the home in 1820. Frost used the home to launch his own successful bolt-making enterprise (which lasted into the 20th century). When a fire badly damaged the home in 1836, Frost had it rebuilt in the Greek Revival style—a very popular architectural mode of the period.

Frost died in 1865, but the home stayed in his family into the 1920s. It remained a private residence afterward, and in 1987, came under the protection of the National Park Service.