By Steve Thornton

Former Negro League baseball player John “Mule” Miles visited Connecticut some years back. He told an audience that despite the adversity African Americans faced playing segregated ball, many persevered for the love of the game. Mule (who could “hit like a mule kicks”) reflected on his childhood: “When I was young, my mother would call me to come in and do the dishes,” he recalled. “I would ask her, ‘can I do ‘em later? There’s still some sunlight! Please let me play ’til the sun goes down.’”

If baseball is America’s pastime, it has been Connecticut’s passion for more than 150 years. Our state can trace the popularity of the game back before the Civil War. Towns, neighborhoods, factories, and churches all had their own teams, from the Hartford Dark Blues (one of the first major league clubs), to the semi-pro New Britain Aviators, to the pick-up teams of the young store clerks who, in the 19th century, played in the early morning hours before businesses opened.

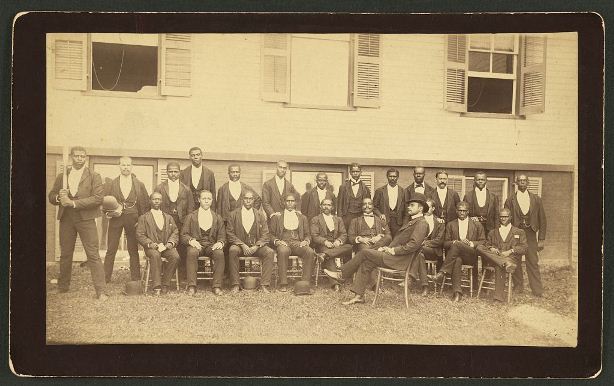

Photograph of the Hartford Dark Blues, taken in 1874–1876 – Connecticut Historical Society, gift of Dr. Austin Kilbourn

The history of this sport, found in a multitude of books and movies, is an important part of American lore. But not that long ago, professional baseball reflected the segregated nature of national life. As the magazine Sporting Life put it in 1891, “Probably in no other business in America is the color line so finely drawn as in baseball.”

Despite demoralizing Jim Crow laws, widespread hostility, and the physical danger of racism, early black ballplayers in this state established a proud tradition of excellence in the game. An understanding of America’s game is not complete until fans know the names of Frank Grant and Moses Fleetwood Walker (black athletes who played for Connecticut integrated teams) as well as they know Ted Williams and Mickey Mantle.

Segregated Baseball in Connecticut

In Connecticut, African Americans played organized baseball as early as 1868, when the Middletown Heroes played in Douglas Park against visiting white teams. In 1886, Moses Walker played for the Waterbury Brassmen, one of eight Eastern League clubs. Walker was born in 1857 “at a way-station on the Underground Railroad,” according to a biographer. He was the first African American to cross over to the major leagues, as a catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings. After baseball, Walker became an author and inventor.

In the Naugatuck Valley, the Ansonia Big Gorhams were part of the short-lived 1891 Connecticut State League. The Gorhams (old English for muddy homestead) also played as one incarnation of the so-called Cuban Giants. None of the players were Cuban, but it was slightly easier to “pass” as Hispanic than black. Ulysses Franklin “Frank” Grant, called the greatest African American ballplayer of the 19th century, was a second baseman and power hitter for Ansonia. Grant is credited with the invention of shin guards—improvised wooden protectors against hostile white players who deliberately slid spikes-first into the black player.

That year the Ansonia team was on the verge of being recruited to Portland, Maine, by the New England League. Opposition grew so strong against the transfer of the “colored chaps” that the Portland team signed nine white players instead. “It became very evident that the place for a club of colored players was a league composed of all colored men, and not in a circuit where all the players were white men,” explained Sporting Life.

Black teams did not often have their own home fields, however, so barnstorming became an important way for them to compete. The semi-pro Corinthians traveled throughout New England before finally settling in Hartford around 1925. Renamed the Hartford Giants, they played their first game against the Manchester Shamrocks. To keep busy they had to advertise in the local newspaper, calling for any and all teams to face them on the field. Hartford hosted the Colored Stars and the Colored Giants from 1925 to 1934, although these teams were probably reorganized under different names with many of the same players.

Johnny “Schoolboy” Taylor

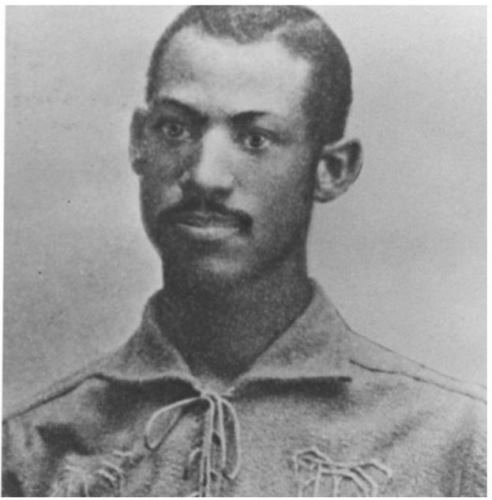

Hartford’s “Schoolboy” Johnny Taylor circa 1936 or 1937, when he played for the New York Cubans – Hartford Courant

In 1920, entrepreneurs formed the National Negro League. From that federation of black clubs came some of baseball’s all-time superstars, notably Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and the young Jackie Robinson. Here again, Connecticut offered its best and brightest to baseball. Johnny “Schoolboy” Taylor was a 1933 graduate of Hartford’s Bulkeley High. Experts considered him a phenomenon on the mound, striking out 22 batters in his last high school game. The New York Yankees expressed interest in signing Taylor until the team recruiter discovered he was an African American. The scout suggested to the pitcher that he join the team as a “real-life” Cuban national, but Taylor refused.

Instead, after his last game with the Bulkeley Maroons, Taylor traveled the semi-pro circuit, pitching for Hartford’s Savitt Gems and the Yantic team of the Norwich State League. He pitched his first no-hitter with the Northwest Athletic Club in Winsted. Taylor’s first big break came when he signed with the New York Cubans. He went on to play with other Negro League teams and then with the Mariano Club in Havana where he became known as “Escolar” Taylor. There, his manager was the legendary Martín Dihigo. Johnny was the student, and Martín was known as “El Maestro.” Dihigo is the only player in history to be inducted into the halls of fame in five countries.

Seemingly mirroring circumstances from Taylor’s life, the award-winning Broadway play Fences by August Wilson tells the tale of Troy Maxson, a former Negro League player too old for the now-integrated major leagues. Angry and bitter, he forbids his son from becoming a college athlete. Fences opened on Broadway in 1987, just three months before Johnny Taylor died.

A sports writer actually posed the Fences dilemma to Taylor in 1976. “What can you do?” Taylor replied. “You can’t live in the past. I’ve always taken things as they come … I like to think that what we did in the 1930s and ’40s by barnstorming with white teams paved the way for the next generation.”

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project