Last Updated: July 10, 2024

By Emily Clark

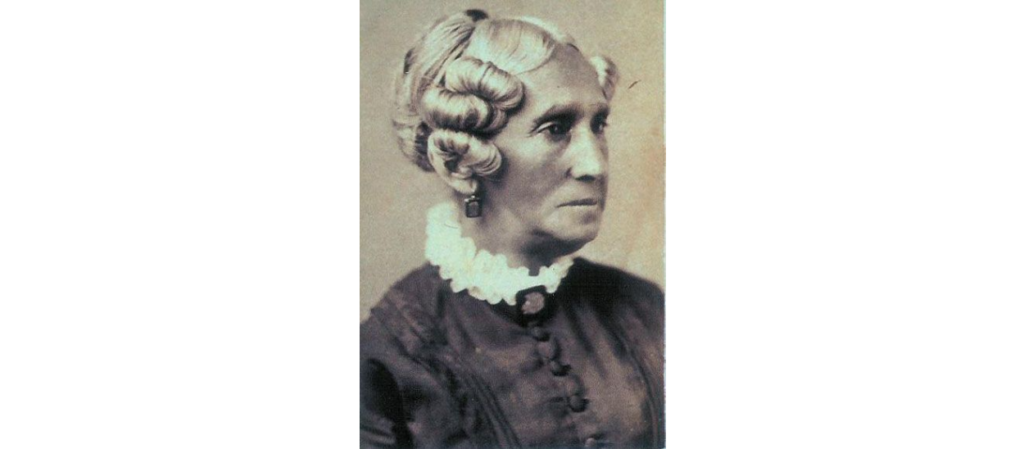

Sarah Harris Fayerweather was a Black activist and abolitionist who fought for school integration in the early 19th century. While other district schools in Connecticut were integrated, Harris’s admission to the Canterbury Female Boarding School in 1832 instigated a local uproar and led to the passage of the state’s Black Law.

Integrating Canterbury Female Boarding School

Canterbury Female Boarding School (now the Prudence Crandall Museum) – Dennis Oparowski, National Park Service, Wikimedia Commons. Used through Public Domain.

Born in Norwich in 1812 to William Monteflora and Sally Prentice Harris, Sarah grew up with a love of learning, as her parents placed great importance on education. Her father, an early advocate for Black civil rights, felt an education was necessary for Black people to progress socially and economically and he worked to ensure that his 12 children had the opportunity to go to school. They initially began at the local school in Norwich.

In early 1832, the Harris family moved about 15 miles north to Canterbury where they had purchased a farm. In that same town, a Quaker educator named Prudence Crandall had recently opened her Canterbury Female Boarding School, an academy for girls. Harris’s future sister-in-law, Maria Davis, worked for Crandall and began sharing copies of William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper The Liberator with the educator.

In September 1832, Harris approached Crandall to request enrollment at the school. Though both women knew that Connecticut enforced segregated schools, Crandall held liberal views on women’s rights and racial equality. After some thought, Crandall accepted Harris as the first Black student in her otherwise all-white institution.

Immediately, an uproar ensued among the residents of Canterbury. The school was forced to briefly close when parents chose to withdraw their daughters in protest of integration. Crandall soon reopened it, however, stating that she was there to educate “Young Ladies and Little Misses of Color.” Crandall admitted young Black women from New York, Providence, Boston, and Philadelphia, which led to continued harassment for both teacher and students as well as the passage of the state’s Black Law. The law passed by the Connecticut General Assembly prevented the teaching of “any colored person who is not an inhabitant of any town of this state” without the town’s permission. After a local mob attempted to burn down the building, Crandall permanently closed the school in late 1834.

Life After Canterbury

Detail from 1850 map Plan of the city of New London, New London County, Connecticut by Collins & Clark denoting a “G. Fairweather” – J.C. Sidney, American Geographical Society Library, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. Used through Public Domain.

By time of the school’s closure, Sarah Harris had married George Fayerweather, a blacksmith originally from Kingston, Rhode Island. They had eight children during their marriage and moved to New London.

At this time, the nation was embroiled in turmoil over abolition, civil rights, and education. Anti-slavery movements rose up around the country, and many people, including the Fayerweathers, worked to support the emancipation of enslaved people. The Fayerweather family became active in the abolition movement and the Underground Railroad, providing food, clothing, shelter, and medicine to freedom seekers. Sarah Fayerweather attended anti-slavery gatherings, even traveling to New York and Boston for such meetings. Throughout her life, she met and worked with other abolitionists and activists such as William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass.

In 1855, George and Sarah Fayerweather moved to Kingston, Rhode Island, where they continued their support for desegregation and freedom by joining the Kingston Anti-Slavery Society and becoming active in the Kingston Congregational Church. Though Fayerweather never realized her dream of becoming a teacher, her younger sister Mary, also a student of Prudence Crandall, became a noted educator.

Over the years, Fayerweather and Prudence Crandall remained in close contact, corresponding often. In 1878, Fayerweather even journeyed from Rhode Island to Kansas to visit her former mentor and lifelong friend. Shortly after returning home, Sarah Harris Fayerweather died at age 66 and was buried beside her husband, George, in Old Fernwood Cemetery in Kingston. Her headstone reads: “Hers was a living example of obedience to faith, devotion to her children, and a tender loving interest in all.” Fayerweather’s papers are part of the Fayerweather Family Papers collection at the University of Rhode Island Library. The Canterbury Female Boarding School is now the Prudence Crandall Museum.

Emily Clark is a freelance writer and an English and Journalism teacher at Amity Regional High School in Woodbridge.

This article has been updated, learn more about content updating on ConnecticutHistory.org here.