By Eve Galanis

The 1988 murder of Richard Reihl sent waves of shock and fear throughout the state of Connecticut, especially among LGBTQ+ communities. Reihl, a gay man from Wethersfield, was the victim of a hate crime when two teens, Sean Burke and Marcos Perez, brutally murdered him in his home. While activists worked tirelessly to advocate for LGBTQ+ individuals for over a decade prior, the incident galvanized and mobilized people. Already grieving from the AIDS epidemic, the community came together to organize and transform LGBTQ+ civil rights legislation in the state for decades to come.

Two Teens Murder Richard Reihl

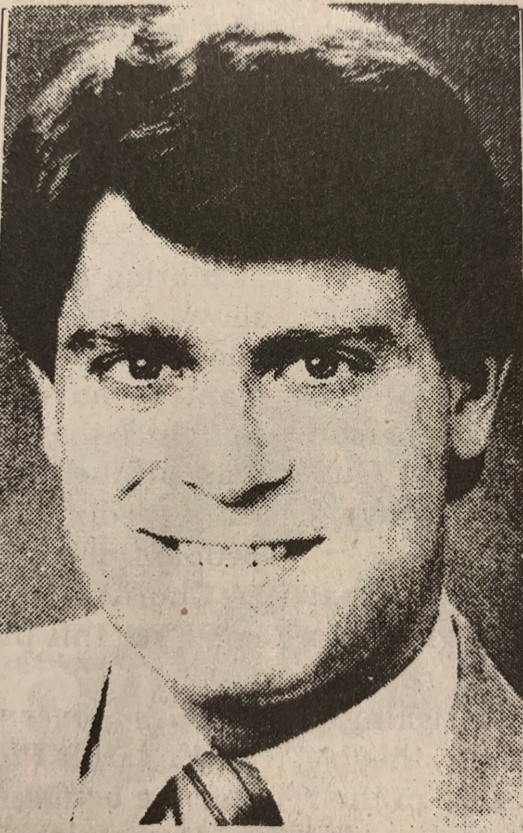

Richard Reihl’s community remembered him as a positive role model. After earning a degree in computers from Boston University, he was working towards a master’s in Business Administration from the University of Hartford at the time of his death. In addition, Reihl worked at Aetna and volunteered teaching economics at Fox Middle School in Hartford. He had a passion for photography and a loving family that was very accepting of his sexuality.

On May 15, 1988, Reihl was leaving Chez Est, a gay bar in Hartford, when he met Sean Burke, 17, and Marcos Perez, 16, in the parking lot. They followed Reihl home to his condominium in Wethersfield. Unbeknown to Reihl, the young men attacked and robbed a man in West Hartford the previous day.

The two teens bound Reihl’s hands and mouth with duct tape and repeatedly struck his head with a log. According to Marcos Perez’s official statement, “Sean went to the fireplace area and picked up a log and we looked at each other, both realizing, this guy’s going to die…I told the guy (Reihl) how I hated fags and how I wanted to kill him.” After the two robbed Reihl, they later returned to his condominium to make sure he was dead; Burke struck him again with the log. Prosecutor Kevin McMahon noted that Burke was implicated in four prior crimes and was involved with a group called the “Reformers,” who targeted and assaulted gay men. Both Burke and Perez pleaded guilty and the court sentenced each to 35-40 years in prison. Perez died of an overdose in 2015, and Burke applied for and received an early release.

Media Portrayed Convicted as “Average Teens”

For those that knew Burke and Perez, the crime took them by surprise. Friends and family of the two teens described them as ambitious, average teenagers. According to his mother, Marcos Perez had an “innate sweetness” and was “a laid-back kid.” Sean Burke was a celebrated athlete at South Catholic High, despite growing up with an incarcerated father, who was in prison for armed robbery and assault. Burke’s defense lawyer, F. Mac Buckley, cited his family’s history and “homophobia amongst most young people,” in an attempt to reduce the sentence to 25 years. As Superior Court Judge Raymond R. Norko imposed the sentence, however, he told Burke he was “a person who has destroyed a wonderful life, a person, Sean, I wish you would have become, who you could have looked up to.”

Watershed Moment for LGBTQ Legislation

Demonstrators protesting in the General Assembly Gallery, February 1990 – GLBTQ Archives, Central Connecticut State University

The murder of Richard Reihl horrified people of Connecticut, sparking vigils, protests, rallies, and meaningful legislation to address bigotry throughout the state. The most immediate result was the foundation of The Anti-Violence Project, an LGBTQ+ civil rights committee founded by Steve Gavron and Shai Cassell. Their mission was to monitor the Reihl case, assist with prosecution, educate the community to protect themselves from bigoted violence, and combat hate crimes in the state. They also worked towards the passage of the Hate Crimes bill by documenting over 250 incidents of anti-gay violence in the state.

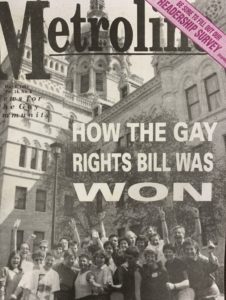

In February 1990, members of the Connecticut Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Civil Rights disrupted the General Assembly meeting and displayed a banner in protest of Governor William O’Neill’s lack of support for the gay rights bill, which legislators had been trying to pass for 17 years. Demonstrators chanted from the visitor’s gallery and eventually the police arrested all twelve protestors.

That same year, Betty Gallo, on behalf of the CT Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Civil Rights, lobbied the General Assembly to enact a second piece of legislation expanding on the Hate Crimes bill; it increased the penalties if the defendant committed the crime due to the victim’s sexual orientation. The General Assembly passed the law, marking the first time the term “sexual orientation” was codified into Connecticut law. (Fourteen years passed before the legislature added the qualifiers “gender identity” and “gender expression” to the law). Finally, in 1991, the General Assembly passed the Gay Rights Bill; a law prohibiting discrimination based on a person’s sexuality in areas of employment, housing, education, and credit. With the Catholic Church historically opposing the various iterations of the bill, legislators modified the language to exempt religious organizations—concessions which still exist in the law today.

Richard Reihl’s Legacy

In 2019, Governor Ned Lamont signed a bill into law that banned LGBTQ+ “panic” defenses in criminal cases—a legal tactic used to excuse a defendant’s violent reaction to a victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity/expression. Despite social and legal progress made over the decades since Reihl’s murder, protecting the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals continues to be an urgent and perpetual matter. While there is still work to be done, the strength of communities coming together to enact change after the Reihl’s tragic death set a standard for LGBTQ+ civil rights across the country.

Eve Galanis is a historian, teacher, and artist based in Connecticut. Her research is primarily centered on historical justice and intersectional critical theory. She currently teaches history and philosophy at Classical Magnet School in Hartford.