The brownstone quarries in Portland, Connecticut, owe their existence to millions of years of prehistoric sediments accumulating in the Connecticut River. Quarried as far back as the 17th century, the brownstone around Portland proved soft enough to allow for carving and polishing, making it one of the most desirable materials for gravestone markers and building construction for nearly three centuries. Portland’s location along the Connecticut River allowed for easy transport throughout the state and, later, the world.

During the height of America’s fascination with brownstone in the late 19th century, quarrying around Portland employed roughly 1,500 men and required a fleet of no less than 25 ships for transporting the material to market. In Portland, brownstone constituted the foundation of schools, churches, and public buildings (such as the Town Hall built in 1894). Some local residences even featured mantels and other brownstone fixtures embedded with the footprints of dinosaurs.

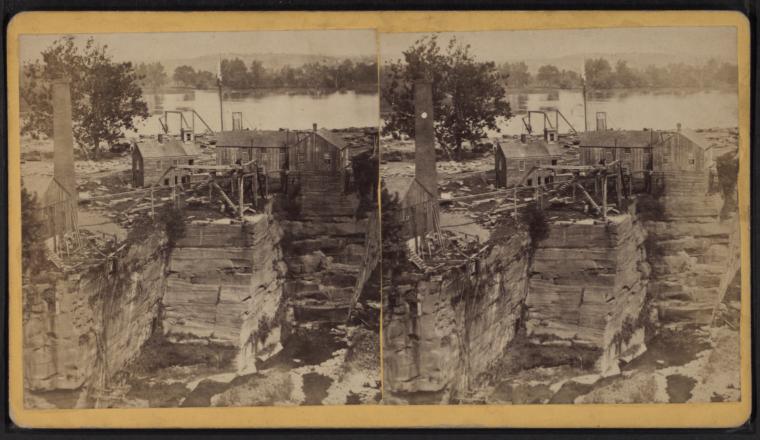

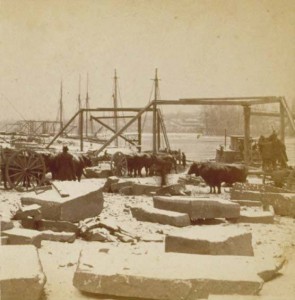

Photograph of the quarry works dock from the early 1900s, Portland – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

Demand Peaks During Brownstone Era

Brownstone quarrying shaped the evolution of the town as numerous shipbuilding and transportation companies, mills, and blacksmith shops arose in support of the industry. In addition, the labor required for quarrying the rock brought in immigrants from Ireland, Sweden, Italy, and elsewhere—changing the demography of Portland. The brownstone quarries even helped name the town, as Portland was a famous quarrying region in England.

The demand for brownstone did not end in Portland, however. In Connecticut, Hartford’s Old State House and numerous buildings on the campus of Wesleyan University utilized brownstone from the area, as did the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch, dedicated in Bushnell Park in Hartford on September 17, 1886.

The great brownstone building era, that lasted into the early 20th century, saw entire rows of houses in New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia constructed out of Connecticut brownstone. The material proved useful in building churches, monuments, and housing for the tremendous waves of immigrants arriving on US shores during this period. Additionally, such ornate structures as the mansions of Senator James Flood in San Francisco, William H. Vanderbilt in New York, and George Pullman in Chicago, demanded large quantities of Portland’s most famous export.

Portland Quarries Designated a National Historic Resource

The end of the brownstone era came about largely through the increased popularity of concrete in the early 20th century. Whereas Portland produced $575,000 worth of brownstone in 1890, that amount dwindled to a mere $55,949 by 1908. The ultimate demise of the industry came in 1936 when the Connecticut River overflowed its banks and filled the nearby quarries with water. While brownstone quarrying carried on for an additional year in small areas above the waterline, attempts to remove the water proved costly and ineffective and operations came to a halt.

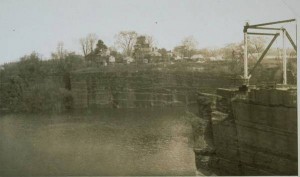

Quarry pit full of water, Portland, 1928 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

For decades after the flood, the quarries remained a fixture of life in Portland, as stories circulated through town of mysterious fish living there and of stolen vehicles, slot machines, and various other items being disposed of in its watery abyss. A renewed appreciation for the importance of the quarries, however, led to a preservation movement that resulted in the National Park Service designating the quarries as a National Historic Resource in May of 2000. Today, in addition to preservation efforts, investors developed a portion of the quarry area into the Brownstone Exploration and Discovery Park, where visitors can come to hike, swim, bike, rock climb, and wake board.