By Thomas Denenberg

Wallace Nutting, a Congregational minister turned photographer, antiquarian, and entrepreneur, played a profound role in the creation of a historical worldview in the state of Connecticut in the early 20th century. Nutting, a native of central Massachusetts, attended Phillips Exeter Academy and Harvard before matriculating at the Hartford Theological Seminary and Union Theological Seminary. Giving up the pulpit for health reasons in 1904, the erstwhile minister turned to his hobby of photography to earn a living. He settled in Southbury in 1906, purchased a house that he christened “Nuttinghame” and began to expand his photography business into an interconnected series of historically-themed products and experiences that fueled the Colonial Revival in America.

Nation’s Centennial Makes an Impression

Nutting’s rise to national prominence is an unlikely narrative and one that the minister put to good use as he marketed his personality. Left fatherless by the Civil War, Nutting shuttled between relatives in New England and the Midwest and spent much of his teenage years in Maine. In 1876, he attended the Philadelphia Centennial where large-scale displays of national pride in the form of nostalgic tableaux, such as the “New England Kitchen” and exhibitions of Revolutionary-era relics, elicited widespread popular comment.

After college and seminary, Nutting embarked on a life of service to the Congregational church in cities such as Minneapolis, Seattle, and Providence, but he soon developed neurasthenia (a now-obsolete term that described a range of mental and physical symptoms associated overwork or stress). Agitated and exhausted, the minister turned to his hobbies in search of relaxation. Nutting and his wife Mariet Griswold Caswell Nutting, whom he married in 1888, toured the mountains and the coast. They joined the throngs who took up bicycling as a means of taking in fresh air.

Nutting became a dedicated amateur photographer working in a pictorial mode, contributing to magazine competitions, and exhibiting his work in a small print shop. He published ever-larger catalogs of platinum prints for sale in 1906, 1908, and 1912. By 1912 consumer demand was so great that the catalog reached 97 pages in length and contained approximately 900 images with extensive commentary.

Demand and Expansion

To meet demand, Nutting hired a group of young women to hand color his photographs and converted Nuttinghame into a compound that approximated the Arts and Crafts communes then springing up in such places as East Aurora, New York, and Rose Valley, Pennsylvania. Nutting organized his barn into a studio, where black-and-white prints passed from colorists’ work stations on to the framing department. “Nuttings,” as they came to be called, could be had in a number of sizes, from very small 2-by-3-inch prints to large 20-by-30-inch prints.

Production reaped immediate profit. By 1914, Nutting’s operation had outgrown the converted cattle barn. The minister and his colorists relocated to Framingham, Massachusetts, and it was from there that Nutting issued his largest catalog, the so-called “Expansible” edition in 1915. By the time of the Expansible catalog, Nutting claimed to be doing a $1,000 in business a day. Nutting offered an image to fit every aesthetic and a picture to fit every budget. There were views of abbeys and cathedrals, mountains and streams, bridges and blossoms, winding roads and pastoral scenes. In all, he offered 19 categories of domestic art photographs, and these sold for between $1.25 and $20, depending on size and frame option.

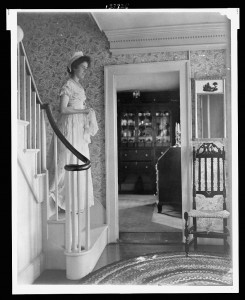

Wallace Nutting, Young woman in colonial dress on steps in Colonial- American home, ca. 1911, photograph – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Representations of Women in Nutting’s Work

Approximately 20% of the 1915 catalog was dedicated to one category: “Colonials.” These costumed tableaux became Nutting’s bread-and-butter product throughout the teens and well into the 1930s. Although Nutting exposed thousands of different colonials, two themes organize the rubric. In a world of “new” women—office girls, suffragettes, and flappers—Nutting’s female models were invariably posed in two extremely conservative modes, “the genteel” and “the productive.” They are “good wives,” spinning like poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Priscilla in “The Courtship of Miles Standish” (1858), or they are 18th-century ladies of leisure, objects set in interior scenes not unlike a chest, chair, stand, or looking glass. They are archetypes of traditional female behavior, and it comes as no surprise to discover that “Colonials” were often given as wedding gifts.

“those who know the pictures, want the chairs”

Concerned about the authenticity of his wildly popular photographs, Nutting moved to secure his own historic interiors by organizing The Wallace Nutting Chain of Colonial Picture Houses. The chain comprised five buildings in three New England states purchased by the minister between 1914 and 1916. With the Chain, Nutting organized a tour of 17th- 18th-century architecture by including structures such as the Joseph Webb House (1752) in Wethersfield, Connecticut, the Wentworth Gardner House (1760) in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the Hazen Garrison (1680) in Haverhill, Massachusetts, the Cutler-Bartlett House (c. 1782) in Newburyport, Massachusetts, and the Ironmaster’s House (c. 1646) in Saugus, Massachusetts. At each property, Nutting undertook extensive and creative restoration work—typified by the introduction of fanciful wall murals into the parlors of the Webb House that literally painted the Chain into a pictorial history of colonial days.

Having gathered a sizable collection of furniture and domestic accessories to use as props in his photographs and to decorate the Chain of Houses, Nutting prototyped them by making full-scale photographs and measured drawings. He then went into the reproduction furniture business. In an early manifesto of integrated marketing, Nutting wrote, “those who know the pictures, want the chairs.” Time and again, Nutting employed a sophisticated pattern of marketing and production with his business lines.

Fan-back Windsor Armchair, Wallace Nutting, ca. 1917-1922 – Yale University Art Gallery

In 1917 he authored a guidebook to American Windsor furniture—one of the first specialty texts on the subject. A year later he issued a mail-order catalog offering dozens of Windsor chairs in a number of historic styles and began to place the line in department stores. All along, tourists could visit the originals in his chain of houses for a 25-cent admission fee. In this way, Nutting organized a market, created demand and filled orders.

Throughout this period of rapid economic growth, Nutting expanded his historically-based conglomerate. His catalogs outgrew the Pilgrim Century aesthetic represented by his reproduction of a Connecticut “Sunflower Chest” to encompass elegant 18th-century forms. In 1921 Nutting published Furniture of the Pilgrim Century, and in 1924 he entered into an agreement with J. P. Morgan Jr. that saw his collection transferred to the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford later that year. In 1928, Nutting published his magnum opus, Furniture Treasury, a tome that remained a standard reference book for generations of collectors.

Travel Books Define New England

Nutting’s stature increased with the publication of the States Beautiful series of travel books in the 1920s. A catchall of the minister’s musings and photographs, the States Beautiful books updated an earlier form of rustic travelogue popular at the turn of the century. They helped define New England and other worthy states, such as Pennsylvania and Virginia, as venerable regions despite the hustle and bustle of modern life. They also solidified Nutting’s image and reputation and made “Old America” what it was, a close ancestor of the biography-based corporations that proved to be so popular in the 20th century.

Wallace Nutting’s images, objects, and texts—from moralizing platinum prints to 17th-century furniture—fed upon one another to create a seamless narrative of colonial forms that made a virtue of the past for the modern era. In this way, Nutting employed the fantasy of Old America to sell an idealized notion of American history to a nation fervently embracing the culture of consumption as an antidote to the worries of modern life. Not only did Nutting provide a “natural, tasteful” picture at little expense, he offered a set of organizing myths for consumers in Connecticut and throughout the United States.

Nutting died in Massachusetts in 1941 and is buried in Maine. The photographs he popularized are widely collected, and the furniture has value and an enthusiastic market among collectors.

Thomas Denenberg, PhD, is Director of Shelburne Museum.