By Stacey Vairo for Connecticut Explored

A visitor to Connecticut’s suburbs can count on seeing an assortment of typical post-war houses in styles such as the ubiquitous Ranch or ever-present Cape. On rare occasions, if he looks very closely, he may spot a strange little house with a low-slung roof covered in rippling tiles. First, he may think, “Why is that house built with square panels?” Looking closer, he may notice light reflecting off the walls and ask himself, “Is that really made of metal?”

By the end of World War II, America faced a massive housing shortage as GIs returned to rebuild their lives and start families. Innovative technologies, including factory-made housing, were devised to address the crisis. Carl Strandlund stumbled almost unwittingly into what contemporary ad campaigns called “The House America Has Been Waiting For,” the porcelain-enameled, steel-framed, factory-made Lustron house, which took its name from the luster of the steel with which it was made.

Connecticut was only ever home to 42 Lustron houses; today fewer than 30 remain, many altered beyond recognition. If you’ve ever come across one of these odd little homes, you’ll know that you’ve met up with your first Lustron—a house that once embodied the fairy-tale promise of the atomic age but met with an ending that will break your heart.

Turning to Metal

The first steel-framed house with metal sheathing in America was built in 1931 by Albert Frey and Lawrence Kocher for the Allied Arts and Building Products Exhibition in New York. (It currently stands on the campus of the New York Institute of Technology.) Two years later, America was introduced to porcelain-enameled-steel homes at the Chicago Century of Progress Exhibition. According to H. Ward Jandl, in Yesterday’s Houses of Tomorrow: Innovative American Homes 1850-1950 published by the Preservation Press in 1991, “The Homes of Tomorrow Exhibition” in Chicago featured a street lined with 12 futuristic homes including 2 steel houses made by General Houses, Inc. and National Houses, Inc. The only known General Homes metal house in Connecticut is on the campus of Connecticut College at 130 Mohegan Avenue in New London; it is currently undergoing renovation and being considered by the National Park Service for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

Porcelain enamel had been used beginning in the late 1920s for businesses such as restaurants and gas stations because the material provided a sanitary and easy-to-maintain surface. It also provided a desirable sleek and streamlined look that immediately evoked a sense of modernity. According to Thomas Jester, author of Twentieth Century Building Materials published by the US Department of the Interior, the White Castle hamburger chain constructed a store made entirely of porcelain-enameled panels in 1929. These same panels were used to build Standard Oil stations—particularly in the Midwest. The Chicago Vitreous Enamel Products Company was one of the manufacturers of these panels for commercial buildings.

The Birth of an Idea

Carl Strandlund, an engineer by training and a self-made entrepreneur, rose to the position of vice president of the Chicago Vitreous Enamel Products Company and would go on to pioneer the use of porcelain enamel in private homes. During World War II most metals had been in short supply, since all resources went to use in the military. In the post-war period steel remained a commodity regulated by the federal government. Strandlund went to Washington to lobby for more steel for Chicago Vitreous to build gas stations.

In a 1949 Collier’s article, Arthur Bartlett wrote, “Mr. Strandlund … was looking for steel with which to build some filling stations… But …the Civilian Production Administration said the new filling stations were out of the question.” Just when Strandlund was ready to give up, Bartlett writes, “A man he didn’t know, whose name he cannot remember, if indeed he ever heard it, said to him: ‘If this enamel stuff you’ve got can turn steel into filling stations, couldn’t you make a house with it, too?’ Whereupon the man faded back into the misty nothing from which he had come.”

With his new plan to build houses, Strandlund gained a number of powerful supporters in Washington, including Wilson Wyatt, the housing administrator, and Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace. Bolstered by political support and the promise of financial backing, Strandlund hired designers and created the Lustron Corporation, a division of Chicago Vitreous Enamel.

Architects Morris H. Beckman and Roy Burton Blass, both young and talented architects and graduates of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, were hired to design the prototype house. Strandlund returned to Washington with plans in hand and promised the government that he would produce 100 houses within 9 months. Each home could be purchased for an affordable $7,000. One major opponent of the plan was George Allen, head of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), who felt the Lustron house was too great a risk. Strandlund’s new political connections, however, helped secure a letter of support from President Truman dated June 30, 1947, that urged George Allen to provide the loans needed to begin production. Those loans came through that same day, just 15 minutes before the RFC’s emergency lending powers expired, and provided Lustron with $15.5 million.

The Lustron House

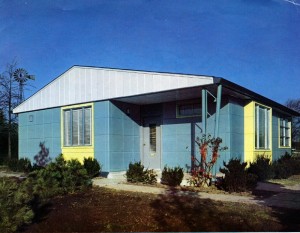

A brochure from the Lustron Corporation described its product: “The all-steel construction makes the Lustron home completely termite proof, vermin proof, and rat proof. It’s also fireproof, decay proof, stain proof, saltwater proof—let’s say it’s almost maintenance proof.” The house was made entirely of porcelain-enameled steel, inside and out, with the exception of asphalt tile floors, a concrete foundation, and aluminum windows. The company offered four models: the Westchester, the Westchester Deluxe, the Newport, and the Meadowbrook. All models were available in two- or three-bedroom plans. Lustron added one-car garages in 1949. The design was sleek, stylish, utilitarian, and compact, with little or no wasted space. The “Deluxe” version featured many built-ins and modern conveniences.

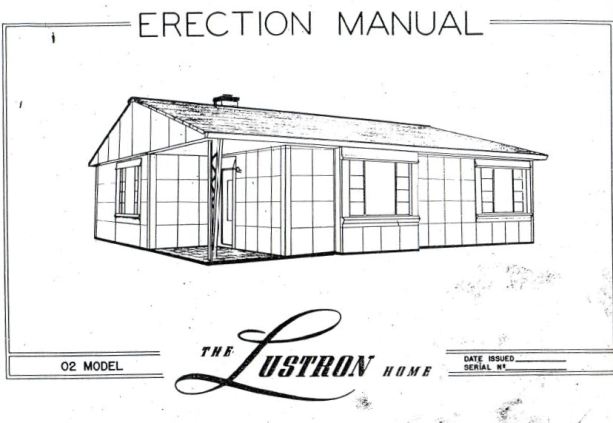

But executing Strandlund’s vision became problematic almost from the start. Although the homes were designed by architects, many of Lustron’s industrial designers were auto-industry veterans. They did not think like builders, and the house ultimately was composed of more than 3,000 parts weighing a total of 12 tons. Lustron offered an “Erection Manual” as a builder’s guide, but building a Lustron was akin to the worst Christmas morning spent assembling children’s toys—though on a much larger scale!

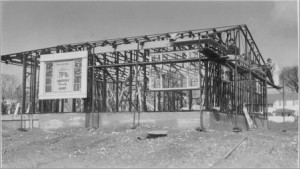

Assembly began with the pouring of a concrete slab. Pre-welded portions of the steel framing were attached to threaded studs embedded in the concrete. Two-by-two-foot panels covered the home’s exterior. A polyvinyl chloride gasket was set between each set of panels to ensure a tight seal. Advertisements boasted that the entire house could be put up in three days or less, but in reality many builders said it took closer to 1,000 man-hours to complete an assembly.

Lustron panels originally were manufactured in four colors: Dove Grey, Surf Blue, Desert Tan, and Maize Yellow. After 1948, the company also offered pink, aqua, green, and white options in the kitchen and bathroom. New buyers were urged to choose their interior wall colors carefully, since they were permanent and unchangeable. In the living, dining, and bedrooms, the flooring was brown asphalt tile, while a gray asphalt tile covered the floors of the bathroom, utility room, and kitchen spaces. Each home’s individual character was meant to be expressed by the carpets, draperies, and furnishings the owners chose.

Heat was provided by an overhead radiant unit that forced hot air into chambers. An early advertisement urged the reader to “Visualize the way the sun’s rays heat the surface of the Earth.” The master bedroom featured a built-in vanity and plenty of closet space. The bathroom contained a built-in medicine cabinet and an extra-long, stamped-steel tub and shower. The kitchen included metal enamel cabinetry and light fixtures and offered a pass-through that allowed for easy serving into the dining area. One of the strangest features was a combination clothes washer and dishwasher called the Automagic, which resided in the utility closet.

An aggressive advertising campaign targeted young families with the idea that a young couple could start in a small, two-bedroom model and move to a larger or more deluxe three-bedroom model as their needs changed. More than 100 demonstration models were built on the East Coast and in the Midwest. These included a South Pacific-themed Lustron displayed on the fifth floor of Bamberger’s department store in Newark, New Jersey.

More Trouble

Issues with production, marketing, and meeting local building codes soon began to tarnish Strandlund’s dream. To sell the homes, a network of carefully selected builder-dealers took orders and constructed the houses on site. Despite more than 10,000 requests for franchises, by May 1949 only 143 dealers were chosen to represent the eastern two-thirds of the country. The builder-dealer network was slow to develop because dealers were required to lay out huge sums of money in order to purchase homes from the factory. Building codes in many states, created to deal with standard wood-frame housing, made building Lustrons nearly impossible in certain areas.

According to the May 1949 edition of Architectural Forum magazine, there was only one Lustron dealer in Connecticut, C-B Homes, Inc., a firm organized in New Haven and run by civil engineer Stanley Chute. Gregory Bardacke served as vice president and was a former consultant to Wilson Wyatt on industrialized housing. Bardacke was not a novice to factory-built homes, the article notes, as he had previously been vice president of the Fuller Corporation, which attempted to mass-market Buckminster Fuller’s famed Dymaxion house. According to the article,

Over the winter, C-B Homes put in foundations and by last month they had erected and sold 17 houses at prices between $9,300 and $9,900, not counting land and land improvement. They currently have six erection crews at work, 12 houses under construction, and a backlog of 61 firm orders.

Sales are moving briskly, the partners say, and Lustron buyers become their best salesmen. Satisfied customers include a White Tower chain executive, who liked the porcelain enamel steel finish of his hamburger stands, and the son of the leading banker. Crute would like to erect 30 houses a month, but, like many Lustron dealers, can’t raise the construction money, which would amount to… $180,000.

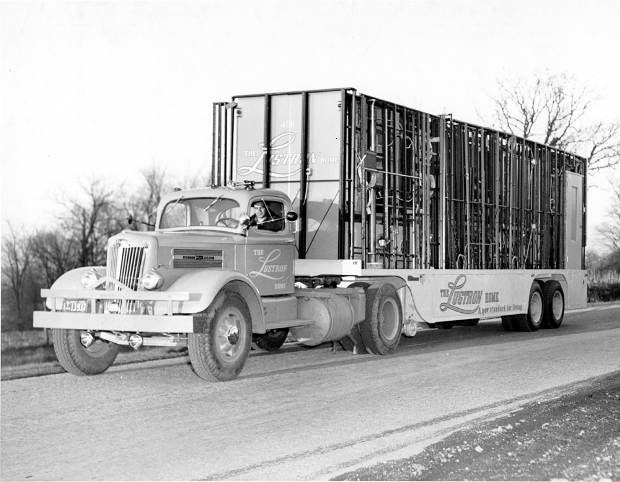

In one sense, Lustron production mimicked the auto industry: Vast amounts of raw materials went into one end of the factory, and a Lustron home emerged at the other—though, unlike a car, the homes came out unassembled. They were made in a factory in Columbus, Ohio, that was larger than one million square feet and, when in full operation, used as much electricity as the city of Columbus. It soon became evident that the $15.5-million start-up loan from the government would not prove adequate to cover the complicated machinery and 12 tons of steel required to produce just one Lustron home.

The windows were installed in the wall sections at the Lustron Factory – National Trust for Historic Preservation

Strandlund had promised the government that he could build 100 houses a day, but production peaked at only 26. Despite efficiency problems, the Lustron Company continued to grow and by mid-1949 had more than 3,000 employees at the factory. Prices for the homes quickly rose an average of $3,000 above the expected sale price. This higher price—about $11,000 including land in Connecticut—put them out of reach for much of the targeted clientele. Even so, production could not keep up with orders.

Long delays in delivery to dealers did not help to bolster the reputation of the company in the eyes of the government. In July 1949, Lustron’s most productive month on record, only 270 homes were built (not the approximately 3,000 per month Strandlund had promised). Loans continued to arrive from the RFC in 1949, but skepticism was growing, and by the end of that year Lustron owed the government more than $32,000,000 in loan repayments.

The press, which once touted Lustron as the house “America has been waiting for,” began to turn hostile. Fortune, Time, and Newsweek all featured articles with damning headlines such as “What’s Stalling Lustron?” and “Whither Lustron?” Strandlund needed time to retool the production line, but the government wasn’t going to give him any more time or money. In February 1950 the government called in Lustron’s loans. In the following months Strandlund and his officials were removed from the factory by a court-appointed receiver, and by June the plant was closed and production ceased. Strandlund lived in obscurity for nearly two decades before moving to Minneapolis in 1973. He died on Christmas Eve in 1974. Thomas Fetters, in his book Lustron Homes: The History of a Postwar Prefabricated Housing Experiment, interviewed former Lustron Vice President Joe Tucker, who said, “[The government foreclosure] broke everybody’s heart. It broke Carl’s. He lived until some years later, but never recovered from the disappointment.” The ‘Top of the Mark’ Motel in Canton, Ohio, was built from the factory’s leftover tiles and stands as a sad reminder of what could have been.

Lustrons Today

The past decade has brought renewed interest in Lustron houses. As the housing stock of the 1950s begins to qualify as historic, books, Web sites, and documentaries have been created to study and celebrate post-war housing. The Lustron Preservation Web site created by the Midwest Office of the National Trust for Historic Preservation is perhaps the most comprehensive resource available and serves as a repository and resource for Lustron owners and enthusiasts. It includes an interactive plan called the “Visual Guide to the Lustron” that allows readers to click on different parts of the structure, change colors, and learn more about the construction of the home.

Fetters documents 42 Lustrons built in Connecticut. According to the Lustron Locator on the Lustron Preservation Web site, Connecticut currently has only 30 remaining. Many (approximately 40 %) of these have been altered beyond recognition, sided with clapboards or sheathed within a larger box of a house. A recent field survey indicated that three of those on the Lustron Registry are gone. Yet, those that remain are a joy to discover. Most are to be found in the southwestern part of the state in Fairfield and New Haven counties.

Stacey Vairo is an architectural historian with the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 8/ No. 1, Winter 2009/2010.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.