By Steve Thornton

On a warm summer day in 1955, 15 domestic workers—maids, cooks, and chauffeurs—packed into a small apartment in a Hartford public housing project. It was a Thursday, the one day of the week their employers granted them time off. They came to hear a trim young man, 30 years old, dressed in a coat and tie. He was Malcolm X, formerly Malcolm Little, a small-time criminal who remade himself into a minister for the Nation of Islam (NOI). Malcolm had just established a house of worship in Springfield, Massachusetts. He was about to do the same in Atlanta, Georgia. But he stopped in Hartford because a woman who traveled to hear Malcolm speak in Springfield was so impressed that she invited him to speak in her city. This he did, talking to working-class members of the black community who made up the majority of the NOI around the country.

Romero, Rachael, Designer, and Wilfred Owen Brigade. Malcolm X, poster, 1976 – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The Nation of Islam Organizes in Hartford

The Hartford NOI group soon grew to 40 people, and by 1956, Malcolm X founded Temple No. 14 in the city’s north end at 2118 Main Street. He spoke to new recruits about the religious tenets of the NOI, but his topics also extended to the international stage and the organic links between black populations everywhere: “The Black man is rising up all over the world and now countries are starting to think before starting a war,” he told the mosque crowd.

Many of the uprisings about which he spoke took place in Africa, in places such as Ethiopia, Kenya, and Algeria. Malcolm wove the stories of black struggles against white racism at home with the fight against white colonialism abroad.

He returned to Hartford at least twice in January 1957. By this time, the FBI and its local office in New Haven tracked and recorded his every move.

Temple 14 moved to 1097 Main Street, where Malcolm spoke again in August, 1959: “We do not advocate violence but we do not turn the other cheek either,” he told his listeners. “When you kill a snake, that is not hate. You are merely protecting yourself.” The next month he narrated a home movie about his first trip to Africa for the Hartford temple members.

All during this period police and federal agents tailed Malcolm, and Malcolm knew it. In answer to a question about the Vietnam draft, the controversial leader replied that he would not tell anyone to become a conscientious objector because he knew the government was listening. He would, however, personally refuse to be drafted.

Malcolm X Tours Connecticut Universities

Although Malcolm X spent a lot of time in Hartford, he also accepted invitations to speak at Connecticut college campuses. He addressed Wesleyan University in February of 1962. An informant reported “there was no disorder whatsoever and he was well-received by the students.” He also received an invitation to speak at the University of Bridgeport.

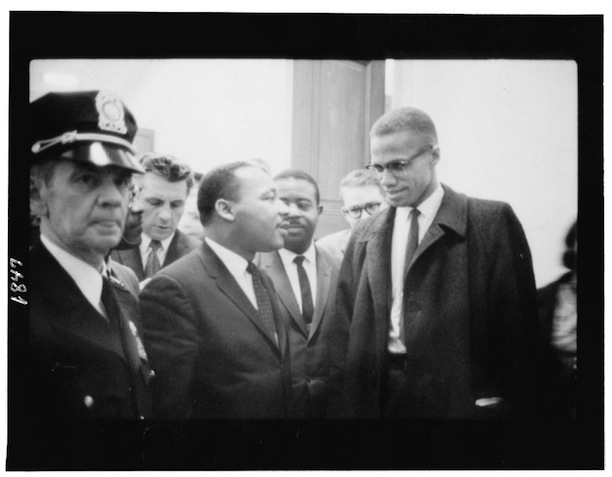

Listening to Malcolm X was often a transforming moment for African Americans, and sometimes for whites as well. It was on June 5, 1963, that Malcolm spoke to his largest Hartford crowd, 800 people at the Bushnell Memorial Hall. The University of Hartford sponsored the event. According to African American writer J. K. Obatala, the speech inspired him to travel to Ghana, his ancestral homeland. “It takes a trip to Africa to realize how American we are,” Obatala wrote.

For this trip Malcolm stayed at the home of Thomas J. X., leader of the Hartford mosque. Newspaper reporter Don Noel spoke to Malcolm by phone at the local minister’s home. Noel later wrote that he preferred Dr. Martin Luther King’s approach to end racism, “but social change is often made meaningful because firebrands insist that problems not be swept under a rug of good feelings.” (Noel’s liberal view contrasted with a newspaper’s obituary for Malcolm in 1965, which called him “the prophet of race war and violence.”)

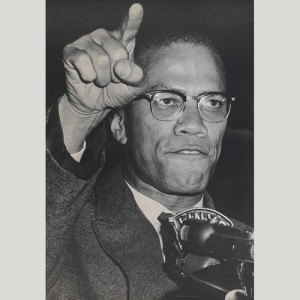

Halftone poster of Malcolm X by Personality Posters, ca. 1967 – National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Only four months later, on October 29, Malcolm X spoke to 700 at the University of Hartford. The speech was moved outside to accommodate the overflow crowd. It was a chilly autumn afternoon, which inspired Malcolm to quip “maybe what I say will make you hot.” In contrast, a representative of Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conferene (SCLC) gave a talk that same day which attracted only 30 people.

In 1963 the freedom struggle was indeed burning hot; racist forces in the South carried on a terror campaign of intimidation and violence. Hartford reporters, however, seemed more interested at the time in Malcolm’s disagreements with other national black leaders. Malcolm warned of “racial bloodshed” that was coming to America. He was assassinated in Harlem on February 21, 1965, three months before his 40th birthday.

Most of white America did not know what to make of Malcolm X during his rise to prominence, except often to fear him. During his short life, he challenged the racist political, economic, and cultural institutions of the United States. Like Nat Turner before him and the Black Panthers after his death, Malcolm defied all the stereotypes of how oppressed people behaved in the quest for liberation.

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project