By Steve Thornton

The history of the early Connecticut women’s movement is not complete without the story of militant suffragist, feminist, anti-imperialist, and labor pioneer Josephine Day Bennett (1880-1961). Bennett played a leading role in the federal passage of the 19th Amendment which guaranteed voting rights for women. As an organizer, speaker, and prison inmate (five days in a Washington, D.C. jail), Bennett shed her family’s class privilege and became a model of tireless advocacy.

Working for Women’s Suffrage

Bennett’s suffragist activity centered on transitioning Connecticut’s women’s movement “from philosophical to political work.” She placed special emphasis on recruiting working women and African Americans, as well as forging links with other social movements. Her first public speaking engagement was at the State Capitol on April 5, 1911, where she shared the stage with Dr. Anna Shaw, president of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA).

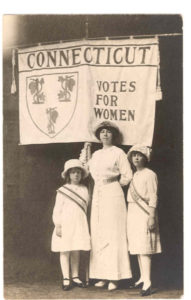

Josephine Bennett with suffrage banner and daughters Tanya and Katherine (ca. 1914) – Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

In 1913 Bennett traveled across Connecticut, organizing the first suffrage group in West Hartford and lecturing at the Killingly Grange. The next year she helped organize the massive suffrage parade of one thousand women through Hartford’s streets, speaking from an open-air car on the corner at Main and Pratt Streets.

At a 1914 congressional committee in Washington D.C., Bennett spoke against the NWSA’s suffrage proposal which required all states to reach a threshold vote before suffrage became law. Instead, Bennett argued for the Susan B. Anthony bill, which required only three-quarters of the states to ratify. This became one of the earliest strategic disagreements between the NWSA and what was to become the National Woman’s Party (NWP).

Greatly affected by the 1917 arrest of Catherine Flanagan (a state woman angered by President Woodrow Wilson’s inaction on promises he made regarding suffrage) Bennett and Katharine Houghton Hepburn quit the Connecticut affiliate of the NWSA and joined the NWP, largely because of its strategic work and militancy. In 1919, Bennett followed in Flanagan’s footsteps, burning a copy of Wilson’s speech and spending five days in jail on a hunger strike.

Bennett campaigned in Maryland in November of that year and returned exhausted after working on behalf of state legislative candidates who would vote for ratification of 19th Amendment. By that time, nineteen states had voted to ratify. Connecticut, however, did not vote to ratify until September 4, 1920.

Josephine Bennett understood that women needed power not only at the ballot box but on the factory floor. As a result, she supported union organizing efforts by garment workers, telephone operators, machinists, typewriter factory strikers, and tobacco workers. She also involved herself with the social and economic impact of trafficking in women. (There were twelve brothels operating in Hartford at the time.)

After the United States entered what became World War I, Josephine turned into an outspoken critic of capitalism’s role in the weapons industry. At one rally she said: “Anyone who profits from war industries at the expense of the United States government is not a patriot but a profiteer. Those who participate in lynchings, mob violence, or petty persecutions are not patriots but ruffians. The true patriot will have interest in the welfare of workers in industries, the negro race, the foreign born, and children.”

Josephine Bennett and the Garment Workers Strike

Josephine in Washington D.C. with a copy of President Wilson’s speech (January 1919) – Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

Bennett’s most significant work may have taken place during the 1919 garment workers strike at Union Place near the train station in Hartford. On the first day of the strike, police protected scabs, roughed up strikers, and had the strikers arrested for violence. Bennett got her brother, George Day, to defend those arrested and she accompanied them to court. She later appeared at a large union support rally, where one speaker dubbed her Hartford’s “City Mother.”

In 1920, Bennett ran for Secretary of State on the Connecticut Farmer-Labor Party slate (an affiliate of the American Labor Party). She was also endorsed by the Socialist Party, and her name appeared on both lines. Following her defeat, she and her husband established the Brookwood Labor College in Katonah, New York. There, she explained, “We teach the truth and we train workers to work in their own movements.”

Bennett counted Katharine Houghton Hepburn and Mary Townsend Seymour among her closest contemporaries. With Hepburn, she led the Connecticut Birth Control League (later Planned Parenthood). With Seymour’s leadership, Bennett became a founding member of the state NAACP in 1917. The initial organizing meeting was held at Seymour’s Hartford home and was attended by such legendary activists as WEB DuBois, James Weldon Johnson, and Mary White Ovington.

But Bennett’s work reached even further still. At a time when an increasing number of women began taking coaches and trains alone, Bennett worked with her sister, Annie Porritt, to help create the Travelers’ Aid Society. She also financially supported her friend Agnes Smedley, the radical journalist and novelist, who aided Indian and Chinese insurgents during their civil wars. By linking disparate social and political movements of the early 20th century, Josephine Bennett was “intersectional” well before the term was invented.

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project