By Steve Thornton

Ann Dunn and Caroline McElroy were unceremoniously escorted to the police station where they were charged with prostitution. The arrest of the two Hartford women came in the summer of 1864 after a raid on two North Main Street brothels. The owners and their families were not treated so harshly: Lyman Waters was released on a bond and a promise to “keep the peace,” and Martha Ford received a suspended sentence. Ford’s daughters got warnings. The four male customers picked up in the raid (whose names were not given to the press) were released with some words of warning but without charge. Dunn and McElroy were sentenced to 45 days in jail. So much for victimless crimes.

The world’s oldest profession thrived in 19th-century Hartford. As in other US cities, prostitution has both prospered and declined, depending the moral and economic climate in which women, primarily, have found themselves. Social reformers have used a variety of methods to rid Hartford of its brothels, but none of them got to the root of the problem. It took radical women like Emma Goldman and Hartford union organizer Rebecca Weiner to identify and propose a cure for the sex trade, the same social and economic conditions that gave rise to prostitution and exist to this day.

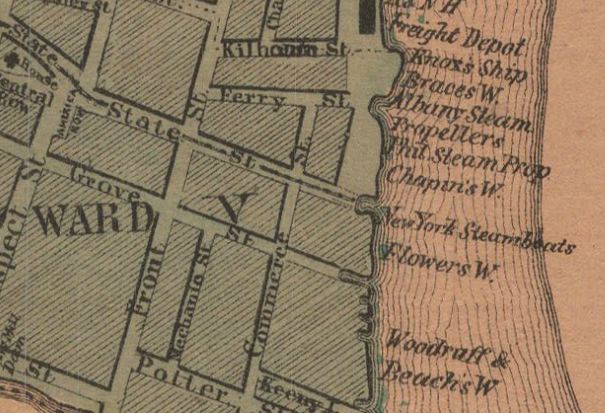

Detail of the Front Street area from the map, Hartford, 1869, published by Baker & Tilden – Connecticut Historical Society

The Tide of Immorality

“Houses of ill fame” were well known to the Hartford public. With names like Kate Pratt’s, Hub Smith’s, and Hunter’s place, these brothels existed mostly in the Front Street neighborhood, but not exclusively. Cadwell’s was located on Woodland Street in Asylum Hill, not far from the respectable homes of Mark Twain and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

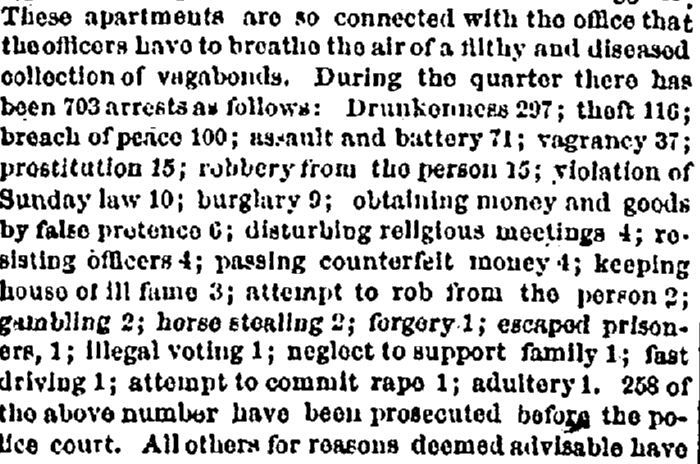

In 1851, Hartford’s Freemen created a Police Court to provide a more effective method of dealing with the rapidly growing vice problem. Up until that time, “inmates of a house of ill fame are arrested, tried and sentenced to the workhouse for thirty days, and yet in less than a week’s time, the same individuals are again in the city pursuing their old avocations,” complained the Hartford Courant. “All the police force in the world cannot suppress the tide of immorality that is setting upon us” without the new court powers, the newspaper argued.

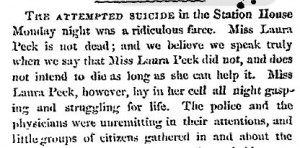

Newspaper account of the attempted suicide by Laura Peck, Hartford Daily Courant, September 12, 1860

Although prostitution was often treated with less severity than other crimes, the consequences of arrest and conviction had grave outcomes for many of the women involved. In September of 1860, Laura Peck was arrested for running a Front Street bordello. Facing humiliation and a criminal record, she tried to hang herself out a window with her shawl. That attempt failed, so Peck tied a rope tightly around her throat. She was found on her jail bunk groaning in pain. The authorities saw her swollen neck and thought she had taken poison. They called in a doctor who treated her with an antidote, but to no avail: her strangulation had been discovered too late.

One young man found himself in a Hartford court in 1850. He was a native of the city who had moved to Buffalo, New York, with his wife and young son. He prospered in business but returned to Hartford to aid his dying mother. The young husband left his family in the care of a male friend. Upon his return he found that his wife had eloped with the friend to a nearby city, abandoning their son. The heart-broken husband’s mental health quickly deteriorated; he started to drink and began to steal to support himself. After a month in jail, he visited a house of prostitution and was astonished to find his wife employed there, sitting “upon the lap of a disgusting ruffian,” according to the news report.

Nelly Adams was arrested by Hartford police for being a “common prostitute” in the summer of 1862. She had apparently dated the son of a well-known Hartford citizen and upon her arrest sent word to have him bail her out. Unfortunately, the messenger gave the note to the young man’s father who showed up at the police station instead. “A scene ensued which we leave to the reader’s imagination,” wrote the Courant.

In the mid 19th-century, the sex trade was so lucrative in the Northeast that it was exported to other parts of the country. An 1866 tragedy at sea underscored this expansion of the sex business. The steamer Evening Star, commanded by Captain Knapp of Stamford, sank off the east coast on its way south from New York. Among the 300 souls who perished were 97 New York prostitutes headed for work in New Orleans.

Solutions: Reform, Raids, and Removal

As the 20th century approached, the Hartford Charity Organization Society reported that there were 12 brothels operating in the city, mostly in immigrant neighborhoods, with a total of at least 400 women. In a city with a population of about 50,000 that equaled one prostitute for every 30 Hartford men.

Attempts to curb the trade varied. In the 1870s moral crusaders tried the personal approach. Seeing prostitution as the function of individual weakness, local charities worked hard to show “degraded girls” the path to redemption. One group opened a public room on the city’s East Side so the women could be uplifted by live music. The efforts solicited only a few customers and were soon closed. The reformers blamed their failure on the influence of rum and the girls’ personal flaws.

In 1898, city reformers used the “ethnic cleansing” approach. Gold Street tenements, some of which housed brothels, were populated by mostly Black and poor Irish families. After a campaign to clean up the neighborhood, the entire street was razed. The demolition succeeded in restoring the historic cemetery nearby, but it did nothing to stop prostitution.

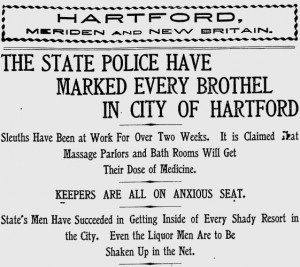

Increased legal scrutiny intensified in the period from 1907 to 1909. Spurred on by the Hartford clergy, the police stormed bordellos in well-publicized raids. As usual, the prostitutes were fined and jailed; the owners got out on bond, and the johns were seldom charged. Hartford police had an ambivalent attitude toward the sex trade, however. Despite the fact that prostitution was clearly illegal, it was also a source of income for local cops. A scandalous trial in 1911 exposed the financial connection between the police and whorehouse owners, but it didn’t take a genius to see that local law enforcement looked the other way when the social reformers weren’t around.

Also in 1911, under pressure by civic groups, Hartford Mayor Edward L. Smith closed all the city’s brothels. Two years later the Vice Commission reported that the closures were successful. But in fact the problem simply moved to the streets and spread throughout the city. One of the first acts of the new police vice squad was a sweep of local restaurants and cafes where streetwalkers would congregate. When the local sex houses closed shop, women were forced out on their own, arguably more independent but also more isolated and vulnerable than when they operated under a common roof.

“Temptation and Defilement”

On March 20, 1911, five days before the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire that killed 146 workers in New York City, Hartford tailors took to the streets for better wages and safer working conditions. Their strike was triggered by the firing of Rebecca Weiner, a young organizer for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). Rebecca had been organizing a union of the alteration tailors at the Sage Allen department store. When owner Norman Allen found out, Rebecca was sacked. Twenty tailors walked out in protest. Allen shipped the strikers’ unfinished work to G. Fox, Brown Thomson, and other downtown stores. The 200 tailors of those establishments refused to help break the strike and were locked out of their jobs.

Rebecca Weiner did not just target the economic and safety conditions of the tailors; her organizing exposed the socially proscribed options that young working women faced. Rebecca knew that Hartford garment workers worked 57 hours a week, long hours which produced wages that were half of what similar work paid in New York. The six-day-a-week schedule meant there was almost no time for a personal life outside of the workplace. Women workers were often prey for a male supervisor who had the power to fine them or withhold wages if they resisted his sexual advances.

A federal Department of Labor study had already found that nearly half the prostitutes surveyed had previously worked in factories and shops before turning tricks. “No working girl can ply her honest calling for less than $6 a week,” Rebecca reported in the ILGWU newspaper, “and be safe from the temptation and defilement to which she is exposed in the polluting atmosphere that environs her struggle for decent living.”

Norman Allen was a formidable foe, determined to beat Rebecca Weiner’s efforts. Not only was he a wealthy capitalist, Allen served as the head of the State Businessmen’s Association and as a Hartford Police Commissioner. This combination of legal, political, and economic muscle was too much for the tailors in 1911 but, thanks to the growing social awareness and determination of women garment workers, over the next few years the ILGWU organized and won a number of other Hartford shops.

Love, Marriage, and Capitalism

Two years after the strike, 500 people crowded into Hartford’s Columbia Hall to hear “the most dangerous woman in America.” Emma Goldman was an anarchist, a feminist, and a speaker with a provocative message. When she wasn’t in jail for “inciting to riot,” or fundraising for imprisoned members of the militant Industrial Workers of the World (the Wobblies), Goldman was writing and speaking on behalf of true liberation for women. On February 12, 1913, she spoke to the Hartford crowd on “Marriage and Love.” Goldman had been widely condemned as an advocate of “free love,” a notion that captured many intellectuals of the left and playwrights of the time but scandalized proper society. “Free love? As if love is anything but free…it can live in no other atmosphere,” she told the enthusiastic audience. Marriage, on the other hand “incapacitates a woman for life’s struggle, annihilates her social consciousness, paralyzes her imagination.”

Emma Goldman’s ideas were considered so inflammatory that she spent much of her adult life being ostracized, forced at times to find shelter in local parks or whorehouses. Those experiences informed her later thinking on prostitution. The Traffic in Women, published in 1910, was a clear-headed analysis of why women ended up selling their bodies. “What is really the cause of the trade in women?” she wrote. “Exploitation, of course… it is merely a question of degree whether she sells herself to one man, in or out of marriage, or to many men.” Goldman cited the studies of noted sociologists and Dr. William Sanger (husband of birth control advocate Margaret Sanger) to prove her point: society’s dominant social customs forced young women either to marry or to sell their bodies in order to survive.

But it was not just capitalism that forced women into the profession. “I refer to the sex question, the very mention of which causes most people moral spasms,” Goldman declared. Women are reared as a sex commodity, she argued, but were kept in the dark about adult sexual relations. No wonder they fell easy prey to prostitution and similar exploitative relationships. Nothing less than a fundamental upheaval of so-called moral values, Goldman concluded, along with the abolition of industrial slavery, could eradicate prostitution.

Hartford’s city fathers were no more likely to heed Emma Goldman’s theories than they were to listen to the union demands of Rebecca Weiner. But for two centuries women have walked the Capitol City’s streets, and neither moralizing nor legal force has put an end to the sex workers’ trade.

Steve Thornton has been a labor union organizer for 35 years and writes on the history of working people.

This article originally appeared on ShoeLeatherHistoryProject.com