By Anthony Roy

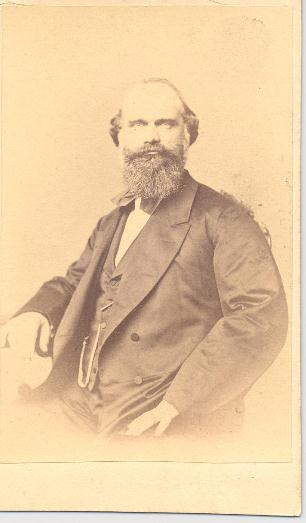

James Goodwin Batterson was the son of a stoneworker. Following his birth in Windsor, Connecticut, in 1823, Batterson moved to the town of New Preston where his father started a marble stone yard in an area known as Marble Valley. At an early age, James Batterson ventured to work in a print shop in Ithaca, New York. Upon his return to Connecticut, the twenty-three year old established himself as the proprietor of a cemetery monument business in Hartford. Although the business’s name changed over the years, Batterson’s central office remained on Hartford’s Main Street for over five decades. In addition to selling stone monuments, Batterson also established himself as a stone dealer and building contractor, as well as an inventor; he created a lathe that produced round, polished stone columns. All of these ventures created opportunities for expansion throughout New England and, ultimately, around the nation.

Batterson was not merely a businessman and inventor. He was an artist, historian, and scientist, as well as a lover of languages. A true Renaissance man, Batterson became remarkably active in his community, especially during the Civil War. He was a man who was both well educated and accomplished. Among the founders of the Hartford Arts Union, he was also a trustee of the Wadsworth Atheneum for 40 years. In addition, he served as a member of the committee that created Hartford’s Bushnell Park. Historian William Hosley noted that Batterson “was the rare individual to have excelled to such a degree in divergent fields. He devoted his life to Hartford . . . and did more than anyone else to burnish Hartford’s national reputation.”

Batterson’s 1901 New York Times obituary captured his depth; he studied art in Europe, wrote poetry, was proficient in Greek and Latin, and spent several years studying and exploring Egypt. The Times noted, “Mr. Batterson passed several years as a geological explorer in the valley of the Nile, becoming honorary Secretary of the Egyptian Exploration Fund and an acknowledged authority on Egyptology. . . . His first winter in Egypt was that of 1858–1859.”

Appreciating the Importance of Monuments

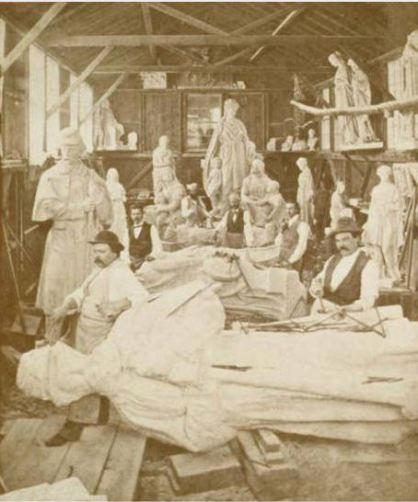

Batterson’s extensive background and artistic interests, combined with his business acumen, guided his foray into the monument business. He desired to re-create in America the lasting monumental tributes he admired throughout Europe and Africa. Early examples of his work include the 1854 statue contracted by the American School for the Deaf and the 1857 General William Jenkins Worth Monument at Broadway and Fifth Street in New York City. Just a few short years later, the Civil War provided Batterson and the nation with the ultimate chronicle worthy of lasting tribute.

When the Civil War erupted, Batterson turned his talents to aiding the Union. In the early weeks of the conflict he helped organize the mobilization of troops. He became an outspoken advocate of Governor William A. Buckingham and President Abraham Lincoln by, among other things, serving as the chairman for the Republican State Central Committee, also known as the “War Committee.” Speaking at a public memorial service held several years after Batterson’s death, William F. Henney announced, “During the war of the Rebellion [Batterson] was of invaluable aid to Connecticut’s Governor Buckingham and the state,” and that Connecticut filled its soldier quotas due to “his untiring energy and genius for organization.” Henney insisted that “Mr. Batterson was a fighter: but he fought with the courage and skill of a trained warrior, with the courtesy of a true knight, with the magnanimity of a gentleman.”

It was during the Civil War that Batterson entered another field of business, one that continues to call Hartford its home. In 1864, he created the Travelers Insurance Company, which pioneered the accident insurance market in the United States, a business model Batterson observed while traveling in Europe.

By the time the Civil War ended, with the sort of carnage that no one in the nation ever imagined, the need for remembrance became paramount. With some 750,000 killed in a mere four years, monuments became one way to memorialize self-sacrifice and duty to the nation.

Anthony Roy is a regional historian and social studies teacher at Connecticut River Academy whose work related to the Forlorn Soldier was completed as a part of his candidacy for a master’s in public history from Central Connecticut State University and as a part of the Connecticut Civil War Commemoration Commission’s efforts to study and inspire awareness of the American Civil War and Connecticut’s involvement in it.

<< Previous – Home – Next >>