By Todd Jones

Between 1934 and 1943, the federal government placed murals in twenty-three Connecticut post offices. Taking the form of both paintings and sculptures, these murals were intended to be of high quality and depicted subject matter that was quaint and comforting. The government wanted these murals to spark an interest in art and offer people an uplifting distraction from the troubles of the Great Depression. Unlike works of art created by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which the post office art is often confused with, these government murals had nothing to do with providing jobs for unemployed artists. Connecticut’s post office murals represent a time when the federal government invested in art for art’s sake.

The Section of Painting and Sculpture

The federal government program responsible for the post office murals was the Section of Painting and Sculpture (later called the Section of Fine Arts). It was under the tutelage of the United States Treasury Department in Washington, DC. During the 1930s, the Great Depression caused rampant unemployment, hunger, and anxiety across the United States and Connecticut. President Franklin Roosevelt, to show citizens that the federal government could still get things done, built hundreds of new post offices. Seeing a new government building constructed in the center of town helped boost the morale of local citizens and showed that the distant federal government had not forgotten about them. The Section of Painting and Sculpture decided which of those post offices got artwork inside.

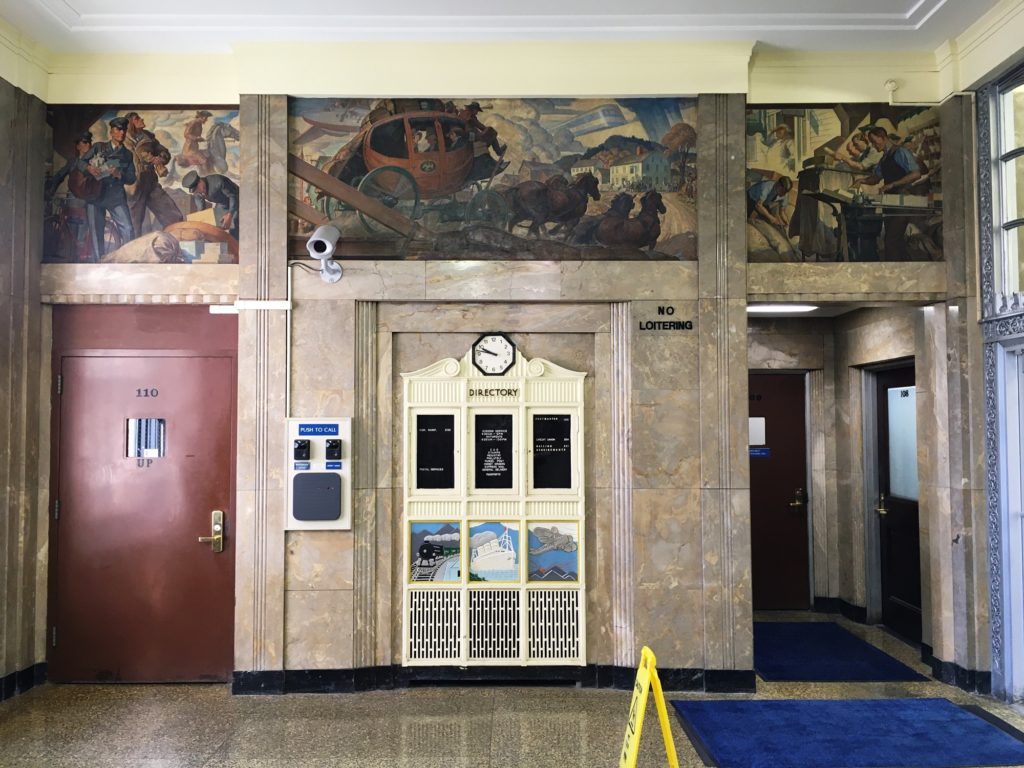

The murals were most often situated above the postmaster’s office door, in view of patrons using the main lobby. In an era before email and cell phones, almost everyone regularly visited the post office to keep in touch with the outside world. The buildings were a perfect place to expose average citizens to art. Not everyone at the time could see fine art in a museum, so the Section brought the fine art to them. The painted murals typically measured ten feet in length and five feet in height. Larger post offices, such as in Bridgeport and New London, had more than one mural.

The Section only picked trained and established artists, since the goal was to create fine quality, lasting artwork. As a result, most of the artists were not from Connecticut, which often upset communities. Most of the artists were appointed, though the Section occasionally held blind competitions.

The Murals

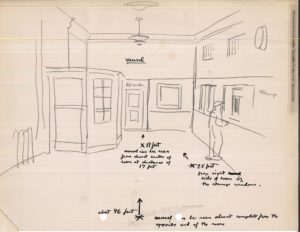

Drawing by artist Frede Vidar depicting mural placement for the interior of the Shelton Post Office. Folder Shelton, Box 12, Entry 133, Record Group 121, National Archives and Records Administration.

Once an artist was chosen, he or she was paid through a contract and typically had one year to complete the mural. During that year, the artist had to send regular updates to the Section staff in Washington, including letters, sketches, and photographs of progress.

The Section took a very active role in the process and controlled specifically how the final mural looked. The Section staff, who were trying very hard to keep their project alive as a permanent government arts program, feared the possibility of offending or upsetting people and causing controversy. As a result, the murals often featured optimistic scenes, especially with historical themes. The colonial past was especially popular in Connecticut. Landscapes were also common since they rarely proved offensive. There were no hints about contemporary problems, such as unemployment, labor strikes, or racial segregation. Mass-production was rarely shown, with the Section preferring depictions of skilled craftsman working by hand or simply showing farming. In a landscape for the Thompsonville mural, the artist replaced the village’s carpet factory with a farm and tobacco barns, which angered many residents. Because of the Section’s stern control over the process, neither residents nor artists had much say in the creation of the artwork.

Post Office Murals vs. WPA Murals

Southington Post Office mural. Photography by Todd Jones. Used with the permission of the United States Postal Service®. All rights reserved.

The WPA, through its Federal Art Project, also made artwork in public buildings at the same time as the Section. The Section and WPA could not have been more dissimilar, however. Unlike the Section, the WPA gave its artists more range to be creative and gave local residents a voice in the creation of artwork. The WPA had an office in New Haven, with Connecticut art experts on staff. By stipulation, the WPA only used Connecticut artists. Not all the artists had extensive art school training like the Section artists, but the WPA’s primary goal was to put unemployed artists to work on government projects. The WPA was by design a jobs program while the Section was an arts program. The Section also had complete jurisdiction over federal government buildings (like post offices), so the WPA only worked in state and local government buildings, such as schools, city halls, and courthouses.

Many of these murals still hang today. All are remnants of the desperate times of the Great Depression and the different strategies used to survive it. The Section’s post office murals represent the government’s attempt to promote the arts while the WPA art represents the government’s attempt to provide employment. One boosted paychecks, the other boosted morale: both provided hope.

Todd Jones is a historian and preservationist. He holds a master of arts degree in public history from Central Connecticut State University.