By Jessica D. Jenkins

During the 19th century Henry Barnard actively served his home state of Connecticut in the field of education and later became a notable reformer on the national level.

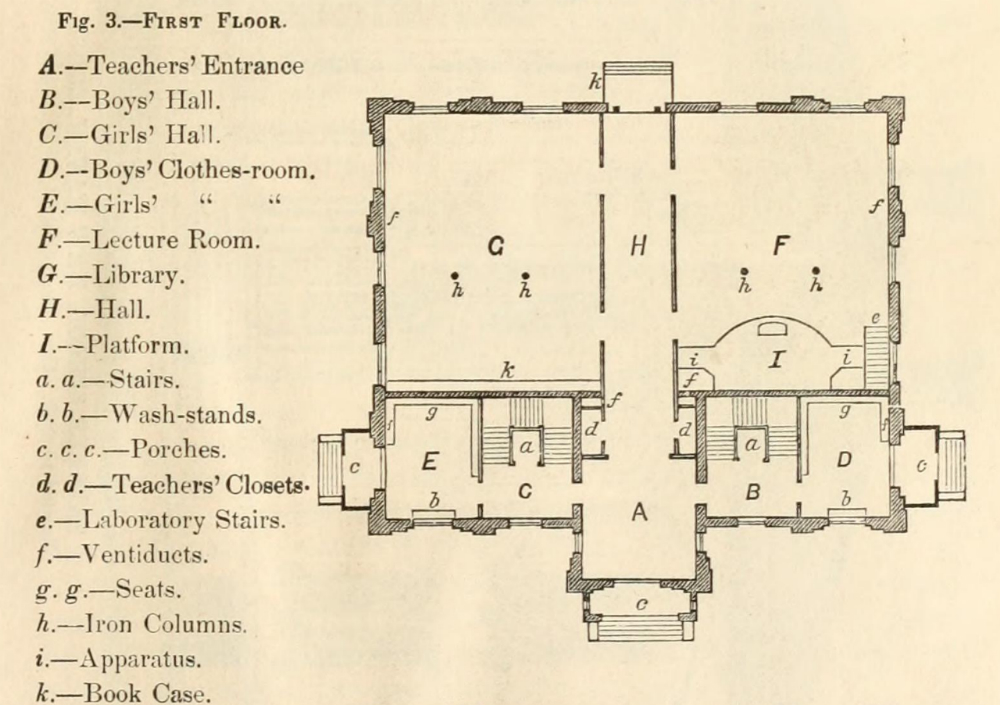

Barnard’s substantial career included service as the first secretary of the Connecticut Board of Education, principal of the New Britain Normal School (the predecessor of Central Connecticut State University), Commissioner of Schools in Rhode Island, chancellor of the University of Wisconsin, president of St. John’s College in Maryland, the first commissioner of Education for the United States, and publisher of the American Journal of Education. Through his work, Barnard played a major role in 19th-century school reform in the US, and the public school system today reflects his theories and practices.

Experiences as a Student and Teacher Shape Bernard’s Mission

Henry Barnard was born on January 24, 1811, in Hartford. His father, Chauncey Barnard, a well-to-do farmer, provided a comfortable life for his family. The advantages of their social class included access to an advanced education and the opportunity to travel. Young Henry did not enjoy his years in public school. (He later remarked that his instructors seemed more like jailors than educators wishing to share captivating information with their students.) Responding to Henry’s many pleading attempts to leave school, the senior Barnard offered his son the opportunity to attend Monson Academy, a private school in Massachusetts.

Henry Barnard

– Connecticut Historical Society

At Monson Academy Barnard began to understand and enjoy the value of education and acquired a lifelong passion for books. As his studies steadily progressed, Barnard became an exceptional student and studied advanced Greek at Hopkins Grammar School in New Haven for a year in preparation for college. In 1826, at the age of 15, Barnard entered Yale University.

At Yale, Barnard earned a reputation for independent thinking and dedication to his course work. He won prizes in English, Latin, and Oratory and became a member of the national honor society, Phi Beta Kappa. During his studies at Yale, Barnard discovered Johann Pestalozzi’s theory of education, which encouraged harmonious intellectual, moral, and physical development. Barnard became a strong proponent of this model and, like Pestalozzi, envisioned schools that were home-like institutions in which teachers actively engaged students in learning by sensory experience.

When Barnard graduated from college in 1830, the president of Yale advised him to teach school for a year and put his theories into practice. Following this advice, Barnard taught public school for one year in Wellsboro, Pennsylvania. The experience reminded him of his own miserable school experiences as a young boy, and he found that neither he nor his students enjoyed the way the public district functioned. Barnard found that the dismal physical environment of the school did not promote enthusiastic learning by his pupils. He also believed that a set of uniform standards, including the incorporation of more varied subjects and better trained teachers, would improve the educational experience of students.

Political Career

Beginning in 1834, after leaving his teaching position in Pennsylvania, Barnard returned to Yale to study law and in 1835 was admitted to the Bar. At this time he decided to spend a year traveling abroad in Europe, though his concern was not sightseeing but meeting influential educators and school reformers in order to expand his own ideas for revising traditional approaches in the US. During his trip he studied the social and educational conditions of the countries he visited and compared them with his own.

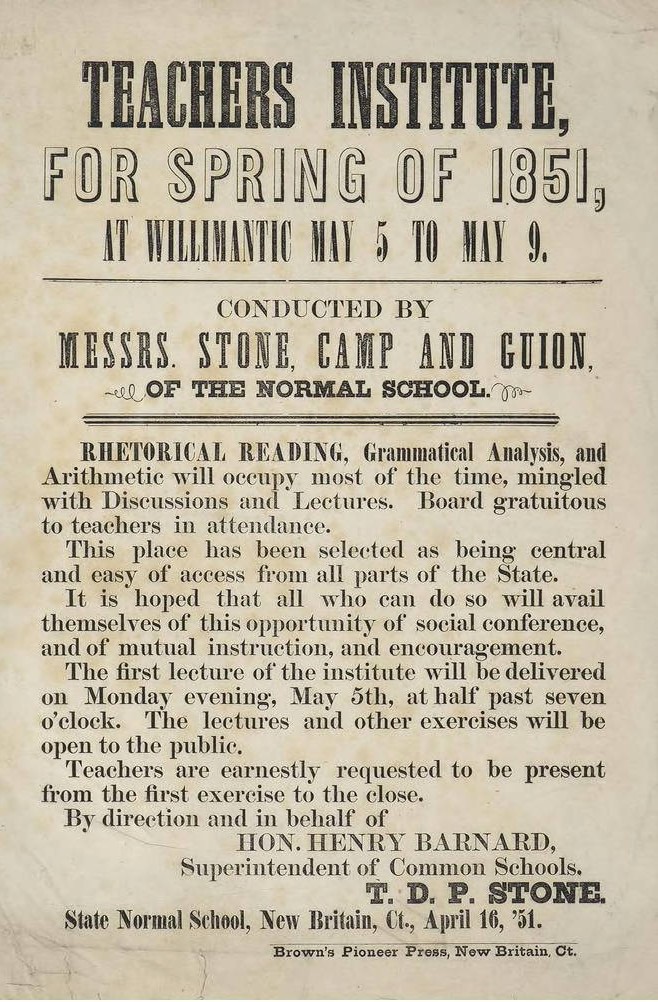

Teachers Institute, 1851, Willimantic, Superintendent of Common Schools, Hon. Henry Barnard – Connecticut Historical Society

In 1837, he was elected to the General Assembly in Hartford where he promoted such philanthropic causes as the incorporation of libraries and care for the mentally ill. As a member of the Connecticut Legislature, he also supported the improvement of the state’s district schools and in 1838 succeeded in passing an act to provide better supervision of those institutions. Later that year Barnard became the first Secretary of the Connecticut Board of Commissioners of Common Schools; he served until 1842 when a political reversal in the state abolished the office and the entire program.

As secretary, he pioneered work in school inspection, recommended textbooks, organized both teachers’ institutes and associations of parents, and pushed for additional legislative measures on education. In assessing Barnard’s life’s work, scholars associate him with a generation of school reformers, largely from privileged backgrounds, who sought to promote harmonious social and civic behavior by instilling moral values in school-age children. For example, by applying principles of the Pestalozzian educational theory as well as the ideas of other reformers, Barnard created and implemented a new model for the common school system in the state that distinguished between primary and secondary school education.

Intended for children under the age of eight, primary schools were to emphasize moral education, something Barnard believed could best be delivered by a female teaching staff. Secondary schools were aimed at children between the ages of 8 and 12, who, Barnard believed, needed professionally trained teachers, both male and female, who could address moral education and the formation of manners. High schools would be broken into two departments: a classical one devoted to traditional subjects and one focused on preparing students to pursue work in commerce, trade, manufacture, and the mechanical arts.

Barnard also advocated for universal education (as defined within the race, gender, and class prejudices of his day). He called for separate departments in district schools for “colored” children and evening schools for working children. All schools would have libraries and a variety of equipment, such as maps and globes, so that teachers could provide instruction on a range of subjects, and students would be empowered to learn beyond what the teacher or their assigned textbooks presented. The entire school system would be overseen by a superintendent, supported by an elected board and annual taxation. Over time many of the ideas of Barnard and other education reformers, such as Horace Mann, were integrated into schools around the country.

Later Years and Initiatives

In 1843, Barnard accepted the offer to survey the common school system of Rhode Island and served as the State Superintendent of Schools until 1849. He instituted similar reforms in Rhode Island as he had in Connecticut and revised the examination methods used by the district schools. After returning to Connecticut following his resignation, Barnard accepted the position of State Superintendent of Schools in Connecticut and continued work on the reform measures he had begun as Secretary of the Board of Commissioners.

In 1858 Barnard accepted the chancellorship of the University of Wisconsin and during the next two years significantly aided the state’s common school system. He became president of St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1866 but resigned in 1867 to become the first US Commissioner of Education. Barnard had long advocated for the establishment of a federal agency to gather and distribute educational information and statistics. As commissioner he planned and organized the work of this agency and prepared extensive reports on education and school legislation.

At age 59, Barnard retired from public office and returned to Hartford to continue his work through the publication of the American Journal of Education. The journal communicated his ideas on education reform to a wide audience. Topics concerning the provision of schooling, administration, training of teachers, school texts, school buildings, and school apparatus expanded under his editorial supervision.

Education had always meant more than district schools, academies, and colleges to Barnard. He felt that community-wide agencies encompassed education as well, and his work with the Connecticut Historical Society demonstrates his convictions. He served as corresponding secretary for the historical society from 1839 to 1846, president from 1854 to 1860, and vice-president from 1863 to 1874. Throughout his life Barnard viewed the Connecticut Historical Society as an educational instrument with the potential to raise the general level of culture and knowledge in the state. He worked to make the society a state-wide organization and encouraged the recruitment of active members from each county. He also supported the publication of a popular magazine of history and genealogy and pushed for the creation of a team of effective speakers on historical subjects who could represent the historical society to local groups.

In 1900 at the age of 89, Henry Barnard died in his hometown of Hartford. He saw himself as the educator of those concerned with the guidance of the younger generations and of the teachers who nurtured them. Highly regarded by his contemporaries, Barnard made a mark on public education in both Connecticut and the nation.

Jessica D. Jenkins is Curator of Collections at the Litchfield Historical Society.