By John Mooney

Throughout the years of the Civil War, Gideon Welles overcame numerous challenges in his position as secretary of the navy. As a Connecticut-born former Democrat, Welles had been appointed to his cabinet position to conciliate northeastern Republicans of similar origins. Nicknamed by Lincoln as “Father Neptune,” Welles soon proved himself more than a political figurehead. During the war he developed the Union navy from a fledgling force into a cutting-edge, world-class fleet. Welles also promoted the development of new naval technologies—the most prominent being ironclad ships—which revolutionized the field of naval warfare. Welles not only faced the strategic and logistical challenges involved in maintaining a blockade of the Southern coast, but also faced vocal attacks from his political rivals and critics. Despite these attacks, Lincoln trusted Welles’s judgment, granting him great independence in deciding naval matters. One of Welles’s fiercest rivals throughout the war was his fellow cabinet member, Secretary of State William H. Seward. On many different occasions Seward attempted to countermand and undermine Welles’s orders and authority. Ironically, Welles and Seward stood together as the only members of Lincoln’s cabinet to serve for the entirety of the Civil War. Although the naval theater of the Civil War has often been portrayed as negligible in comparison to the war’s land campaigns, it is important to discern the undeniable role Welles and the navy played in securing Union victory.

Criticisms and Accusations

Secretary of State William Henry Seward. Seward disapproved of Gideon Welles, regarding him as simplistic and brash. – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

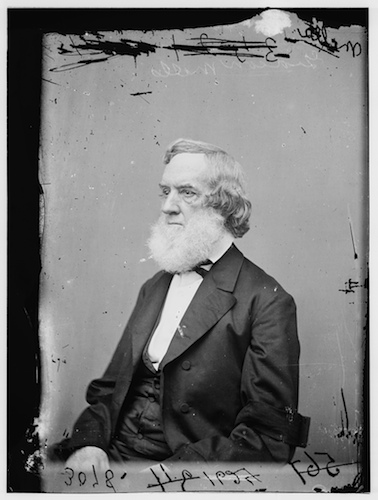

When Gideon Welles was appointed to Lincoln’s cabinet as secretary of the navy in March of 1861, he faced significant criticism from within the cabinet as well as outside of it. Secretary of State William Seward, a scheming member of Lincoln’s cabinet, was unimpressed with Lincoln’s choice in Welles. Indeed, the two secretaries were nearly polar opposites in both physical appearance and personality. Welles was an unpretentious man of strict morals whose unkempt appearance was often the subject of ridicule. The reserved Secretary Seward portrayed himself as a man of sophistication and dignity, yet often engaged in clandestine plans to subvert the power of his rivals.

Seward’s opposition to Welles became apparent even before the start of the war. In the months leading up to the Battle of Fort Sumter, Seward attempted to undermine Welles’s role in overseeing the navy as part of a plan to redirect military resupply efforts away from Fort Sumter and towards Fort Pickens in Florida. Captain M. C. Meigs and Officer David Dixon Porter, under the direction of Seward, wrote an order to transfer Commodore Silas Stringham, head of the Bureau of Detail, into the command of a secret resupply of Fort Pickens. In their orders, they replaced Stringham with Commodore Samuel Barron and invested him with several powers equal to those of the secretary of the navy. Seward subsequently had Lincoln sign the order during a busy period where the president did not have time to review its contents thoroughly. The signed order soon found its way to Welles, who immediately confronted the president. Lincoln, surprised to find his own signature on the document, rescinded the order. This proved to be a critical decision. Stringham had been appointed to the new bureau by Welles with the directive to ascertain the loyalty of naval officers of Southern heritage. Unbeknownst to both Meigs and Porter, Barron was a Southern officer and a close friend of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Mere weeks after Lincoln had canceled the order, Barren left the navy to join the rebelling Confederates in Richmond, Virginia.

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, ca. 1855-1866. Welles was well known for his disheveled appearance. Long after his beard had grown white, Welles continued to wear his mismatched brown wig – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Brady-Handy Collection

Welles not only endured the schemes of Steward, but also faced criticism from the senate. Early in the war, Welles attempted to hasten the acquisition of naval vessels for the Union by hiring his brother-in-law, George D. Morgan, as a purchasing agent for the navy. Morgan’s role was to purchase merchant vessels for use by the navy, receiving a two-and-a-half-percent fee on each sale. Unfortunately for Welles, Senator John P. Hale, the head of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee, publicly expressed that such an arrangement was sheer nepotism and launched a public investigation into the purchasing agreement. In reality, Hale was outraged that Welles had not sought to contract purchases through some of his own close associates and hoped to force Welles to resign through the pressure of the investigation. The lack of any evidence of misuse of government funds, combined with Lincoln’s support and approval of Welles, brought an end to the investigation. Throughout his career as secretary, Welles faced continuous disapproval from Seward, Hale, and other critics, yet not once during the war did Lincoln ever lose trust in his “Father Neptune.” Lincoln realized that the outspoken Welles was prone to making political enemies but also saw immense value in his superb ability to organize and manage the navy.

The Blockade

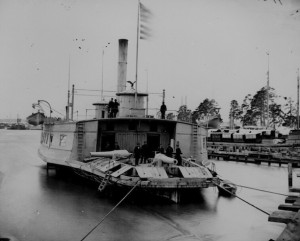

Gideon Welles’s primary duty at the beginning of the Civil War was to implement and secure a full blockade of Confederate ports to prevent trade and communication between the South and Europe. This proved to be a monumental task as the Union had only a small, outdated fleet of 76 ships. Many of these ships were sailing vessels which proved useless as blockade vessels in the rising age of fast, steam-powered ships. Welles took immediate action by ordering the creation of the well-known “ninety day gunboats.” These versatile small steamer vessels were highly maneuverable and proved to be indispensable for the blockade. Welles also hired purchasing agents to acquire merchant vessels for the navy’s use. Although Welles’s hiring of his own brother-in-law brought about a scandal, it had also been a boon for the navy. Morgan, alone, was able to purchase 89 ships for the navy at a total cost of $3.5 million—a well-priced deal for the time. At the end of the first year of the war, about half of the navy’s 264 ships were comprised of purchased and converted merchant ships.

The USS Commodore Perry, a former ferry, was one of the countless civilian ships bought by the Navy and converted for use in the war. – National Archives

The blockade not only required a massive naval force but also needed to be well coordinated. Duty schedules had to be enacted and local refueling stations needed to be created to resupply the ships manning the coast. Welles ordered the creation of a Naval Strategy Board, the first of its kind, to calculate the logistics of the blockade. The creation of this board was a precursor to the development of the military staff officer positions that exist today. The Blockade Strategy Board was comprised of two naval officers, Samuel Francis DuPont and Charles Henry Davis, as well as Major John Gross Bernard of the army, and a civilian, Alexander Dallas Bache. This eclectic collective met throughout the summer of 1861, ensuring successful implementation of the blockade.

The New Ironclads

One of the greatest technological developments during the Civil War was the creation of ironclad warships which were used extensively in battles throughout the war. In 1861, when Virginia seceded, Union forces abandoned the Norfolk naval shipyard, sinking and burning the ships at the base to prevent their capture. Soon after, Confederate forces captured the shipyard and began working to restore a scuttled Union ship, the USS Merrimack. The Southerners renamed the ship, the Virginia, and began to transform it by removing its mast and sails and fitting its hull with iron plating.

Welles received vague intelligence concerning the Confederacy’s ironclad project and in response began organizing a similar Union undertaking. Welles formed a board of three officers, known as the Ironclad Board, to review 17 different submissions of possible ironclad designs. Cornelius Bushnell had already received the President’s approval of his design when he submitted it to the Ironclad Board. Bushnell’s schematics illustrated a flat-bottomed iron vessel with a single rotating turret on its deck. Bushnell’s ironclad represented a radical shift from popular ship designs of the period. Although initially skeptical of its merits, the Ironclad Board, prompted by Welles’s and Lincoln’s approval of the design, decided to fund construction of Bushnell’s ship. On March 3, 1862, Bushnell’s ironclad, named the Monitor, was completed and provided to the navy, perfectly timed for its first engagement.

The engagement between the Monitor and the Merrimack, which later became known as the Battle of Hampton Roads, did not result in a decisive victory for either the Union or the Confederacy – National Archives

On March 8, 1862, President Lincoln received a telegram from the Union navy’s Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia, which stated that the Confederate’s ironclad had been completed and had subsequently sunk, captured, or disabled the ships of an entire Union squadron. This telegram spread panic throughout Lincoln’s cabinet. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton was particularly fearful of the Merrimack’s abilities. Stanton believed it possible that the Merrimack would be able to approach and bombard any northern coastal city with impunity. Welles countered Stanton’s fears calmly, trusting in Bushnell’s newly completed Monitor. Welles was also fully aware that the shallow basin of the Potomac would prevent the Merrimack from reaching Washington. Stanton, however, persisted in his belief that Washington would be attacked and ordered the sinking of barges and other private boats along the width of the Potomac to create an impassable barrier. Before Stanton’s order could be enacted, another telegram reached Washington declaring that the Merrimack and the Monitor had engaged each other with the battle ending in the Merrimack’s withdrawal to the Norfolk shipyard. Upon hearing the news, Welles, realizing that a barrier in the Potomac would cut off supplies and communication between the Capitol and the military, immediately rescinded Stanton’s prior order.

A marble statue of Gideon Welles was placed on the Connecticut State Capitol building’s facade ca. 1933 to commemorate his achievements both within the state and as Secretary of the Navy – Courtesy of Stacey Renee

Despite instilling ongoing fear in the North, the Merrimack faced the Union navy only once more, in a similarly indecisive battle against the Monitor and a large paddle steamer, the USS Vanderbilt. On May 11, 1862, the day after the Norfolk shipyard had been recaptured by Union forces, the Merrimack was blown up by its own crew to prevent its capture. The ship had become trapped on the James River between the Union navy at Norfolk and the shallow waters that prevented it from escaping to Richmond. Both the Union and the Confederacy would continue to build and use ironclads throughout the war, but the Union’s Monitor design would prove more effective. Gideon Welles, confident in these new ships’ abilities, was a strong supporter of their use in the war. Indeed, Welles supported the creation of many other nontraditional naval designs, including ramming ships and mortar rafts. It was his focus on technology, combined with his efforts to enlarge the navy, which made Welles such a significant Civil War figure. Through his war efforts, Gideon Welles revolutionized the American navy, transforming a pitiful collection of mostly outdated sailing ships into one of the strongest naval fleets in the world.

John Mooney lives in Bristol, Connecticut, with his ever-helpful girlfriend he met while working towards a bachelor of arts degree in history from Green Mountain College in Poultney, Vermont, which he received in 2013. He is currently continuing his education at Central Connecticut State University in the public history degree program.

This article was published as part of a semester-long graduate student project at Central Connecticut State University that examined Civil War monuments and their histories in and around the State Capitol in Hartford, Connecticut.

<< Previous – Home – Next >>