By Tara M. Cantore

The Hall of Flags in the Connecticut State Capitol is filled with the history of the state’s military past. The building’s west wing contains the battle flags of the state’s military from the Civil War to the War on Terror. A vast majority of the flags in the oak and glass cabinets come from the Civil War era, installed in the capitol shortly after the building opened in 1879.

In 1865 the Connecticut General Assembly declared battle flags to be sacred. They announced, “the battle-torn and battle-hallowed flags of our brave regiments be most sacredly and tenderly preserved, and used only on public occasions of great solemnity and importance.” Prior to 1879, the flags were stored at the State Arsenal. The new capitol building opened in January 1879. During the January session of the General Assembly, legislators passed House Joint Resolution No. 141 that stated: “Resolved by this Assembly. That the comptroller, adjutant-general, and quartermaster-general shall be a board to have charge of the battle flags of the State, now stored at the state arsenal, and they are directed to cause suitable cases to be erected in the Capitol, and the flags placed therein.” With the resolution approved on March 11, 1879, officials placed a total of 80 flags in the capitol in 1879 as part of a grand parade. Today, 55 Civil War flags are on display in the Hall of Flags.

Carrying the Regiment’s Colors

The battle flags, also known as “the colors,” were a rallying point for troops during the Civil War. Carrying the colors into battle was an honor and privilege, as well as a dangerous job. Those that carried the colors needed to be courageous. The flags also symbolized national and regional pride for the soldiers as they went into battle.

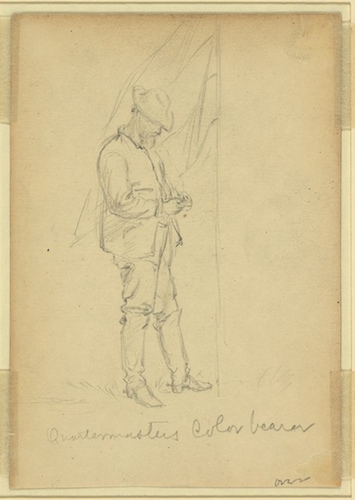

A sketch of a color-bearer from the Civil War era by Alfred Waud, ca. 1860-65. It was considered an honor and privilege to carry the colors into battle – Alfred R. Waud. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Used through Public Domain.

There were practical reasons for the flags as well, as the regimental flags marked the position of the unit during battle. The smoke and confusion of battle often scattered participants across the field. The flag served as a visual rallying point for soldiers and also marked the area where to attack the enemy.

Each unit had two flag or color-bearers. One carried the state flag and the other carried the national flag. It was an honor to carry your unit’s colors, and it was an honor to capture the colors from the enemy. Each national flag indicated the unit to whom it belonged, that way, if the enemy captured the national colors, dishonor fell only on the individual unit, rather than the entire Union. In order to protect the colors from capture, in addition to having two color-bearers, each unit had two color guards. Tremendous acclaim fell upon the soldier who saved his unit’s colors or captured the colors of the enemy.

The colors were considered so sacred that, even when wounded and close to death, Col. John L. Chatfield of the 6th Connecticut Regiment showed greater concern for the regiment’s colors than for himself. On July 18, 1862, Chatfield’s leg shattered below his knee and he received a wound in his right hand. When comrades carried him to the back of his regiment and gave him transportation to head home, he asked about the colors. After learning they were safe, he replied, “Thank God for that! I am so glad they are safe! Keep them, keep them, as long as there is a thread left.”

Sergeant David Kittler carried the state flag of the 11th Connecticut at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. When he received an order to charge forward he refused because he did not have the support of a full color guard. A Connecticut officer immediately slashed him with a sword for being a coward. Corporal Henry A. Eastman had no issue with charging forward, and felt honored to carry the state colors. Eastman said, “Give me the colors!” He grabbed them from Kittler and moved forward while the regiment cheered him on.

Connecticut’s Flag Creators

Hartford sign painter and artist, Frederick F. Rice, made the first national flags purchased for Connecticut’s troops during the Civil War. Connecticut Adjutant General Joseph Williams and Quartermaster General John M. Hathaway asked him to make the flags. Each flag that Rice created was hand-painted and unique. The national flags he created had eagles in their cantons. The eagles appear to be protecting the federal shield from attack on the flag.

During the early part of the war, Rice painted the majority of Connecticut’s regimental flags. These flags had a split shield that included the Connecticut seal on it. The last flags ordered from Rice were for the 14th, 17th, 19th, and 20th regiments.

Pictured is a scene from Main Street in Hartford during the historic Battle Flag Parade on September 17, 1879 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

In January of 1862, Connecticut’s Governor William A. Buckingham appointed his son-in-law, William Aiken, quartermaster general for the state. In the summer of 1862 it became Aiken’s job to purchase the colors for the state’s military. John Almy lobbied Aiken to use Tiffany & Co. for all future flag purchases. The Almy family was close friends with the Tiffany family, and Almy was therefore able to purchase flags from Tiffany at a less expensive price than other states paid. The first flags ordered from Tiffany & Co. were for the 18th, 21st, 19th, and 20th regiments.

The Connecticut troops found that flags painted on silk split easily in the wind, especially during the winter months. Aiken then began ordering embroidered flags from Tiffany. Aiken told Tiffany the design he wanted embroidered on the flag, and Tiffany created a pattern. The flag contained the Connecticut crest of a small eagle on a wreath mounted on the shield. A gold border surrounded the shield. The embroidered flags had a three-dimensional eagle and lettering. The final cost for the embroidered flags ranged from $100–$160 each. With inflation today, the cost equates to approximately $2,266–$3,626.

Battle Flag Day—September 17, 1879

In 1879 the Connecticut General Assembly decided to transfer the Civil War battle flags from the state arsenal into cabinets in the new state capitol building. A committee decided to have a removal ceremony on Wednesday, September 17, 1879, the 17th anniversary of the Battle of Antietam. Invitations to attend and escort their old colors went out to all of the soldiers and sailors that served in the war. General Joseph R. Hawley proved a unanimous selection as the grand marshal for the Battle Flag Day Parade.

The planned festivities quickly turned into a tremendous celebration. The Hartford Office of the Board of School Visitors closed schools that day. Officials solicited individuals and businesses to help finance the festivities. A committee created to report on the condition of the flags found some flags still in good condition, but others almost completely destroyed. A committee of ladies worked diligently to prepare the flags for the celebration.

Battle Flag Day on Main Street, September 1879, Hartford – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

Over 10,000 veterans participated in the parade. Each corps met up in East Park in Hartford where they placed tents for the headquarters of each organization and where each unit chose officers and color-bearers for the day, as well as reported on the number of men present. According to reports, it was a beautiful clear day. Visitors began to arrive in Hartford at 7:00 am and people filled the streets throughout the day. Hartford received more than 100,000 visitors that day.

The parade started around 12:30 pm and made its way from Ford Street towards the state arsenal. Throughout the march, the on-lookers greeted veterans, cheering and waving handkerchiefs. Beautiful patriotic decorations filled the streets. In addition to the veterans marching, there were bands and music, state and city officials comprised 14 carriages, and even the disabled veterans participated, occupying two large four-horse omnibuses and several decorated carriages.

After arriving at the capitol, the veteran battalion formed a line that faced the north front of the building, with the color-bearers in the center. Once assembled a mass of veterans reached from the capitol all the way to the terrace. The bands played “Marching Through Georgia.” General Hawley made a formal presentation of the battle flags to Governor Charles B. Andrews on a platform raised in front of the building. Hawley addressed the crowd and the governor. In his speech he stated, “We come in obedience to an invitation to our beloved Commonwealth, to bring these eighty flags from their temporary resting place to their final home, in this new and beautiful Capitol.” Governor Andrews went to formerly accept the flags. He said:

For more than four years of conflict wherever the camp was the hardest, wherever the siege was the fiercest, wherever the march was the longest, wherever the fight was the sorest, they were always to be seen. . . . They come back to use riddled by shot, tattered and torn, blackened and grimed with the smoke and powder of battle, but they bring us no word of flight or dishonor. They speak to us of the many displays of manly and heroic virtues which amid the duties of war have illustrated the character of the sons of Connecticut.

After the speeches, one at a time, the color-bearers brought their battle-torn flags forward. Various reports state that many had tear-filled eyes during this solemn ceremony. When the ceremony finished, all the veterans made their way to dining tents at Bushnell Park.

A call went out to the women of Hartford to cook and bake for the veterans for the celebration. The women donated an abundance of food. Businesses also made donations. Years later reports stated that Battle Flag Day was one of the greatest days for the city of Hartford.

Restoring Connecticut’s War-Torn Battle Flags

The first effort to restore the Civil War battle flags was in 1939, 60 years after their arrival in the Hall of Flags. According to an article in the Hartford Courant, Mrs. Katherine F. Richey, known at the time for her remarkable flag restoration skills, took on the restoration of 20 flags. Originally asked to fund the project in 1939 for $5,000, the General Assembly refused, but eventually appropriated $1,000 for the work. In 1939, each flag’s estimated restoration costs were $50 to $60— approximately $840 to $1,008 today.

During the 1980s the Connecticut State Capitol underwent a major interior restoration. During that restoration, Geraldine (Gerry) Caughman, a member of the League of Women Voters and a League tour guide at the capitol, offered to donate a few hours of her time to move the flags during the renovations. When Gerry opened the display cases, she found that time had taken a toll on the Civil War battle flags. In an article in the Hartford Courant on December 30, 1985, Gerry is quoted saying, “A lot of them had literally fallen right off the staff. . . . We couldn’t touch all of them cause they were too fragile.” The project was only supposed to take up a few hours of Gerry’s time, but it turned into 26-year mission for her. She became the caretaker of the flags, and earned the nickname of the “Flag Lady” at the capitol.

The flags of the 11th, 14th, and 16th Regiments are located in this glass cabinet in the Hall of Flags at the Connecticut State Capitol building – Courtesy of Stacey Renee

Gerry asked Dr. Patricia A. Trautman at the University of Connecticut to examine and estimate the restoration costs. While Trautman was examining the flags, the Connecticut General Assembly team overseeing the capitol restoration walked into the room. They immediately saw the flags were in an extremely delicate and fragile state and from that moment forward displayed a determination to preserve these treasures. UConn received the $110,000 contract to restore the flags. Dr. Trautman, along with a team of eight history and textile experts, took part in the project.

In an article in the New York Times from 1985, Dr. Trautman said that restoring the flags was going to be difficult due to their condition. She added that there had been some previous efforts in the past to preserve and restore some of them.

There are several different methods to restore and preserve textile pieces. During the 1980s UConn restoration, the method used was to sandwich the flags between two layers of a thin and sheer fabric called crepeline. The crepeline fabric is the piece meant to take the brunt of the abuse from the elements while still allowing the flags to be visible.

By 1987 the repair of the flags was put on hold, when officials realized it was too expensive to preserve all 110 flags. UConn finished work on 73 of the flags at the cost of $147,000, and estimated a cost of more than $300,000 to finish the work on the remaining 37 flags. The legislative management committee paid $75,000 towards the work and UConn paid $35,000 of the cost to restore the 73 flags. In an article in the Hartford Courant, Rep. Paul D. Abererombie, R-North Haven, said, “the degree of work has been much more extensive than the team expected when it estimated it would cost about $1,000 each to restore the flags.”

State leaders agreed to let UConn out of the contract to restore all the flags. In 1987 there was no decision made on what to do with the remaining 37.

Future of Connecticut’s Battle Flags

Since the restoration project during the 1980s, a few flags have been restored each year. According to the meeting minutes from the Capitol Preservation and Restoration Commission, the average cost to restore a flag today is approximately $10,000.

In order to preserve the history of the battle flags, Gerry Caughman wrote and published a book in 2006 titled, Qui Transtulit Sustinet: Connecticut Battle Flag Collection. The two volume series describes the history and current state of the battle flags, and provides several illustrations and photographs of the relics.

In 2006, officials appropriated $50,000 for the conservation of the battle flags. An additional $50,000 was approved each year for 2007, 2008, and 2009. The flags of the 18th, 24th, and 28th Regiments were conserved and placed on display in 2008. In 2009, however, the funding was put on hold for the project.

A plaque was dedicated to the “Flag Lady” Gerry Caughman and placed in the Hall of Flags on September 20, 2013, for all her hard work preserving the flags – Courtesy of Stacey Renee

Gerry Caughman, the beloved “Flag Lady” of the capitol building, died on July 7, 2012, at the age of 78. With the passing of Gerry, the “mother” to these old relics, one may wonder the future of the flags. According to Eric Connery, Support Services Administrator for the Joint Committee on Legislative Management for the Connecticut General Assembly, funding was provided to restore five flags over the course of the next two to three years. Due to their fragile nature, some of the flags that still need conservation will not be able to be displayed on their poles in the Hall of Flags, but will be displayed in glass frames.

The flags represent a very important piece of Connecticut’s history. Thousands of men died protecting the Union, and these flags show future generations where we have come from as well as the stories behind these battle-scarred relics.

Tara M. Cantore is an adjunct professor teaching English and public speaking at Paier College of Art, and a graduate student in US history at Central Connecticut State University.

This article was published as part of a semester-long graduate student project at Central Connecticut State University that examined Civil War monuments and their histories in and around the State Capitol in Hartford, Connecticut.

<< Previous – Home – Next >>