By Steve Thornton

In 1899, the John Farris Music store in Hartford received an unusual request. It was a letter, relayed from Australia, asking for information on Hosea Easton, a Hartford man who had recently died in Sydney. A notice was placed in the Hartford Courant requesting information from local residents. No one could identify him, the newspaper reported.

In fact, Hosea Easton was the son of Sampson Easton, a respected citizen, and the grandson of the well-known intellectual and abolitionist Reverend Hosea Easton, the original pastor of Hartford’s first black church.

Reverend Hosea Easton (September 1, 1798 – July 6, 1837) Intellectual and Activist

The Eastons were one of New England’s most notable 19th-century African American families. Their lineage can be traced back to the 1690s after taking their surname from Nicholas Easton, a slaveholder and a founder of Newport, Rhode Island. Nicholas Easton’s relatives emancipated their slaves in the Quaker faith. Caesar Easton became a landowner who fought off a series of challenges by white men attempting to claim his property as their own. His son James Easton moved the family to Eastern Massachusetts and worked actively in the early movement for black freedom.

James was a veteran of the American Revolutionary War and possessed Native American (Wampanoag) heritage. He was a blacksmith and iron worker who sold industrial iron to big Boston construction projects and later opened an academic and trade school for black youth, which his son Hosea attended in 1816.

Hosea learned courage and activism as a child. The Congregational church attended by the Easton family built a “negro porch” in the back of the church and required all black members of the congregation to sit there during services. James and Sarah Easton refused. The family continued to sit on the main floor of the church until being physically removed.

This same struggle took place in a number of churches the Eastons attempted to join. As a child, the Reverend Hosea Easton engaged in at least five acts of civil disobedience, until he was a teenager. He and his family were the first African Americans known to have engaged in sit-ins for racial justice.

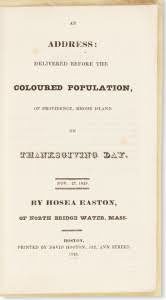

Copy of the 1828 Thanksgiving Day Address by Reverend Hosea Easton – The Shoeleather History Project

Hosea, married Louisa Matrick in the 1820s and became a minister and effective abolitionist agitator. Reverend Hosea first came to public attention in 1828 with a Thanksgiving Day Address in Providence, Rhode Island, attacking racism and slavery. It was a frank, explicit, angry condemnation of the brutalities of slavery, mixed with the call for spiritual uplift of black people. In this sermon he also criticized the African Colonization Society, a movement led by whites to remove all American blacks from the country. This was a “diabolical pursuit, Reverend Hosea preached, “where they will steal the sons of Africa . . . bring them to America, keep them in bondage for centuries . . . then transport them back to Africa by which means America gets all her drudgery done at little expense.”

In 1833 Rev. Hosea and Louisa Easton moved from Massachusetts to Hartford with their son, Sampson. Hosea became the first pastor of Talcott Street Congregational Church, and established the first school for black youth. He later established the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church in Hartford.

As free northern blacks formed their own institutions and communities, racist violence against them dramatically increased. Across the North in the 1830s there were deadly riots in Cincinnati, Boston, New York, and Pittsburgh.

For a three day period starting June 8, 1835, white crowds harassed and beat African Americans in Hartford’s Front and Talcott Street area and destroyed a number of black dwellings. In 1836 the Methodist Episcopal Church was burned down. One apparent cause of these attacks was an organized effort for black men’s suffrage led by James Mars, a church deacon and former enslaved man born in Connecticut.

Rev. Hosea Easton died on July 6, 1837, at 38 years of age. The cause of his death is not known. Yet he might have written his own terminal diagnosis in his Treatise: “The effect of these discouragements are everywhere manifest among the colored people. I will venture to say, from my own experience and observation, that hundreds of them come to an untimely grave, by no other disease than . . . oppression.”

Sampson Easton (1829 – ?) A Courageous and Honorable Life

Sampson Easton was the son of Hosea and Louisa, born in 1829, who moved to Hartford with them. He was named after his great-grandfather on his mother’s side, Sampson Dunbar of Massachusetts.

Sampson Easton was an entrepreneur. He was listed as a livery driver and a hack driver during 1858 and 1859. He also owned the Easton Academy of Music on Commerce Street in 1860, where he crafted, repaired, and played banjos, fiddles, and possibly other musical instruments. That may have been where his dance hall was also located. He was not a famous man, unlike his father and other relatives (or, indeed, his own son); but there are three incidents that show the same courage and anti-slavery politics that Sampson learned from his parents.

In 1858 Sam Easton attempted to save “Aunt Mary” Robinson, a longtime friend, from being killed by her husband, Ben. They and others held an impromptu party at the Robinsons’ apartment, playing music and dancing. Ben Robinson was drunk and abusive toward his wife, angered that she was dancing with Sampson. By all accounts, Easton tried to peacefully de-escalate the situation, even after Ben assaulted him. Easton and friends started to leave, when Ben stabbed Mary many times. Easton put himself in the middle of the attack and was wounded. Mary Robinson died; Ben Robinson was sent to prison. Easton was a witness at Ben’s trial.

Two years later, in April, 1861, a Mrs. Thomas Flaherty attempted to commit suicide by jumping off a railroad bridge into the Connecticut River. Easton jumped in the icy water and rescued her. He brought her to shore and she rewarded him with a slap in the face.

The moment for which Sam Easton might best be remembered occurred on December 2, 1859. A dance was held at State House square, sponsored by Engine No. 5 of the Hartford Fire Department. At about 2:00am on Saturday morning, some of the dancers saw a light emanating from the cupola of the State House. They called on police who climbed to the belfry and apprehended Sampson Easton, “a colored citizen of this city,” and his white companion from New Haven, Charles Boyle.

But Easton and Boyle had completed their objective, “draping the figure of Justice upon the cupola with sable fabric, in view of the execution that was to take place in Charlottesville, Virginia during the day,” according to a news report. The condemned man was Connecticut-born John Brown, the white abolitionist who electrified the nation with his October raid on the government arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

The pro-slavery Democrats of the time insisted Easton had been hired by a Republican to perform the symbolic action, but Easton denied it. He was perfectly capable of acting on his own volition, Easton wrote in rebuttal.

Easton and Boyle spent the night in the Hartford jail while authorities tried to figure out how to charge them. It was decided that the two ”could be charged with neither insurrection nor resurrection,” and were released at noon, less than an hour after John Brown died.

Hosea Easton ( March 6, 1849- June 23, 1899) Stage Actor, Musical Virtuoso, “Prince of the Banjoists”

Arguably the most well-known of the Eastons was Sampson’s son (and Rev. Easton’s namesake) Hosea Easton. He was born in 1849.

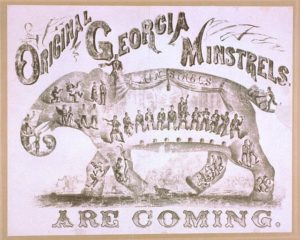

At some point in his youth, Hosea picked up one of the banjos his father, Sampson, made. He later joined the Georgia Minstrels, frequent favorites in Hartford. Minstrel shows and other variety acts often played at the Roberts Opera House and Allyn Hall, both venues that were a short walk from Easton’s neighborhood. It’s likely a young Hosea saw them perform there.

Original Georgia Minstrels are coming (O.V. Schubert, c1876) – Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The Georgia Minstrels featured, among others, “Dick Little, the greatest banjoist living.” What they did not feature was white performers singing and playing in blackface, as virtually all such acts did beginning in the 1830s. White blackface acts perpetuated the offensive stereotype that deliberately corrupted the public image of African Americans among the white population, but the Georgia Minstrels received an endorsement from none other than the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who once said: “No imputation can be brought against them of presenting anything offensive to the eye or ear.”

By the time he was 27 years old, Hosea Easton left Hartford and traveled to Hobart, Australia, as a member of the Georgia Minstrels. The troupe was at the height of their popularity along the Pacific circuit, especially in Australia, New Zealand, and China. A Sydney Mail reviewer singled out Easton when he wrote that “he draws considerably on theology and temperance for his witticisms.”

Easton also performed with groups such as the Mastodon Minstrels in Hong Kong. The various American shows proved popular, but for a variety of reasons (mostly the performers not getting paid, competition between troupes who took the same names, and outright racism of owners and promoters), there was little stability and frequent turnover.

Quickly, Easton became an audience favorite, entertaining with “clever banjo solos riffed on popular airs” which “earned frequent encores.” Crowds flocked, requiring special trains to bring fans into urban venues from the outlying countryside.

Hosea Easton spent the rest of his life in Australia, an extraordinarily beloved figure, until his death. When he required hospitalization in 1899, other performers staged a benefit concert to help pay his medical costs. After Easton succumbed to cancer, his funeral became a parade as hundreds of admirers and musicians marched with his casket down the street to the Waverley Cemetery. His grave is still an attraction there.

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project