By Nancy Finlay

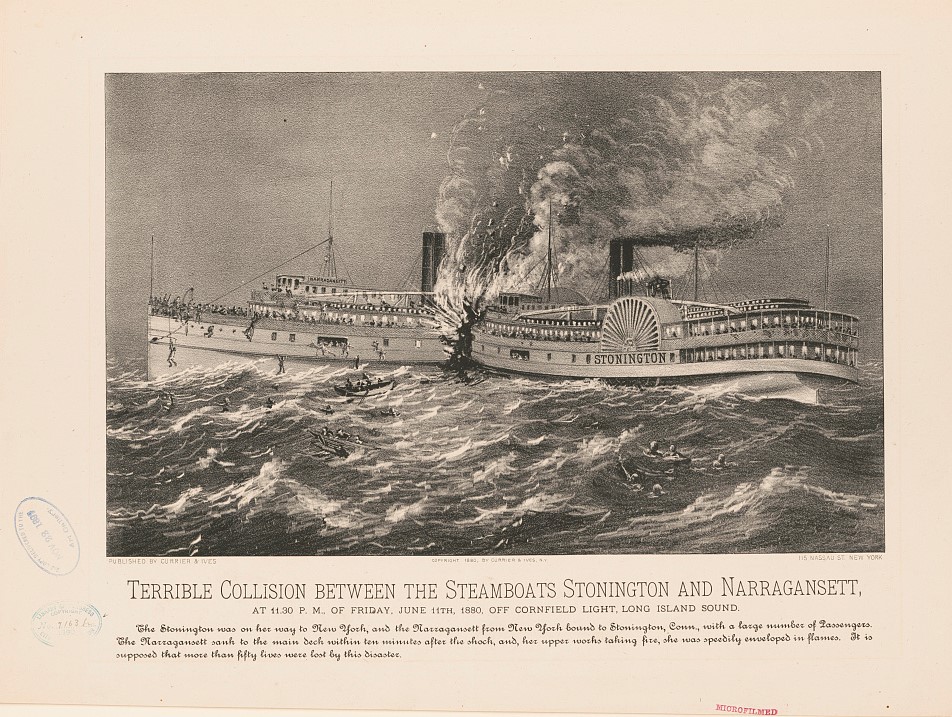

The S.S. Narragansett left the North River pier in New York City at 5:00 p.m. on June 11, 1880, bound for Stonington, Connecticut, and Providence, Rhode Island. Her sister ship, the S.S. Stonington, left the steamboat dock in Stonington shortly after 9:30 p.m., bound for New York. The boats were unknowingly on a collision course. The subsequent tragedy involving the Stonington and the Narragansett resulted in the death of dozens, massive destruction, and a media frenzy.

The Night of the Crash

By 11:30 p.m. on the night of the crash, most of the passengers on both vessels were asleep. They included businessmen traveling between New York, Providence, and Boston, and families bound for summer resorts along the New England coast. Conditions were crowded, with many passengers sleeping on benches and on the deck as well as in the berths and cabins.

Out on Long Island Sound, the night was so dark and foggy that no lights were visible, and the ships repeatedly sounded their whistles to indicate their positions. Once the westbound Stonington passed the mouth of the Connecticut River and was about three miles off Cornfield Point in Old Saybrook, Joseph Silvia, the Portuguese American seaman at her wheel, heard the whistle of the eastbound Narragansett off her port bow. Moments later, there was a terrific crash as the Stonington plowed into the other vessel, ripping a huge hole in her starboard side. Water began to pour in and a gas meter exploded, starting a fire that quickly raged out of control. The Stonington was also damaged and was taking on water but crew managed to patch the leaks with canvas and boards and with the ship’s pumps going full blast, the vessel was in no immediate danger of sinking.

The Race to Escape

Baseball card depicting John Reilly, first baseman for the Cincinnati Stars, who survived the disaster – Wikimedia Commons

Terrified passengers crowded the decks of both steamboats, while both crews attempted to launch lifeboats and life rafts. Some passengers on the Narragansett found themselves trapped in their cabins as the vessel foundered and the passageways filled with smoke and flames. Others leaped from the deck into the water to escape the fire and drowned before they could be picked up by one of the lifeboats. Their names and stories made headlines. John Reilly, a first baseman with the Cincinnati Stars, spent over an hour in the water before being rescued. Emily Dix, the wife of a Brookyn, New York broker, watched as her three children and their Irish nursemaid all drowned after their lifeboat capsized. Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Stilson of Atlanta, Georgia, survived the wreck, but their two young children perished in the fire. Ominously, one passenger on the Stonington, Charles Guiteau, took his survival of the crash as a sign he was destined for a higher purpose. A little over a year later, Guiteau assassinated President James Garfield.

Despite its damage, the Stonington was able to limp back to port at Stonington. Several boats came to aid the passengers and crew of the Narragansett. The Narragansett, having sustained the brunt of the crash, required towing back into port. Because the ship did not keep an accurate passenger list, the number of deaths resulting from the collision was never accurately determined. It is likely that between 50 and 70 people lost their lives that night.

Media Coverage and the Aftermath

Following the inquest into the collision between the two Stonington Line steamships, the steamboat company paid a fine for failing to adhere to the rules governing steamboat commerce and both captains lost their licenses. The newspapers criticized the Narragansett’s captain, William S. Young, for ordering his crew into the boats and then leaving his ship himself while many passengers remained on board. In addition, he failed to have sufficient officers and watchmen on board. Simultaneously, the newspapers also criticized Captain George F. Nye of the Stonington for failing to provide adequate aid to the sinking Narragansett.

While other maritime incidents were not uncommon, fatal steamboat accidents on Long Island Sound were relatively rare—the wrecks of the steamboat Lexington in 1840 and the steamer Atlantic in 1846 are notable exceptions. The public appetite for news and images of such disasters was apparently insatiable, however. For weeks, newspapers were filled with lurid accounts of the collision between the Stonington and the Narragansett and eye-witness testimony from the inquest into its cause. Currier & Ives published a dramatic lithograph showing the moment when the bow of the Stonington struck the Narragansett and burst into flames. Harper’s Weekly published a long article illustrated with numerous wood engravings depicting not only the collision but also its aftermath—the injured and distraught survivors, a man and a woman finding a dead child on a beach, and divers preparing to descend to the sunken Narragansett to search for bodies.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.