By Kenneth Minkema

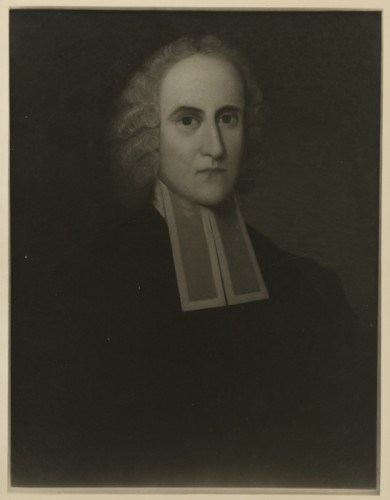

Jonathan Edwards, arguably one of the most significant religious figures in US history, was a theologian, philosopher, pastor, revivalist, educator, and missionary. An adherent of Reformed Puritan theology, he engaged the new methods and approaches of the Enlightenment, incorporating them in innovative ways into his inherited religious worldview.

Edwards spent most of his career as a Congregational minister in Northampton, Massachusetts. There, he participated in two major religious revivals, including the Great Awakening (a transatlantic evangelical movement that swept the British-American colonies in the 1740s). He became the chief theorist and apologist for revivalism and a fountainhead of the new evangelicalism. Dismissed in 1750 from Northampton after a bitter, protracted controversy over qualifications for church membership, he assumed the post of missionary to Native Americans at Stockbridge, Massachusetts, the following year. In 1757 he received a call to become the president of the College of New Jersey, which later became Princeton University. He held this position for only a few months before dying on March 22, 1758, following a bad reaction to a smallpox inoculation.

Edwards’ Formative Years in Connecticut

Though most of his mature life was spent in Massachusetts, Edwards was a Connecticut native. He was born on October 5, 1703, in Windsor Farms (present day South Windsor), on the east side of the Connecticut River across from Windsor. His parents were Timothy Edwards and Esther Stoddard Edwards. Timothy was the minister of Windsor Farms, where he served from 1694 to 1758. The couple had 11 children: 10 daughters and one son.

The community and family in which Edwards grew up shaped his education, temperament, and spiritual life. His father, a gifted leader, had a reputation as a powerful preacher who had seen several periods of religious “stirs” in his congregation. Edwards’ mother and his many sisters were known for their intelligence, learning, and wit. In their home, where Timothy ran a preparatory school for local boys, Jonathan and his sisters were trained in classical learning.

Edwards matriculated in 1716 in the Connecticut Collegiate School. At that time, the college was separated into three locations: Saybrook, New Haven, and Wethersfield. For several years Edwards attended the Wethersfield branch under the tutelage of his kinsman Elisha Williams. The young Edwards also attended the town’s church, where his uncle, Stephen Mix, was the minister. By 1718, negotiations to find a single, central location for the college had been completed and the New Haven site was chosen along with a new name, Yale College, after a benefactor. Students from the other branches arrived, but Edwards and several others, displeased with their tutor, returned temporarily to Wethersfield. It was not until his senior year that Edwards actually resided in New Haven. During this time, no doubt, he became more acquainted with Sarah Pierpont, daughter of the Reverend James Pierpont. Eventually, Jonathan and Sarah would marry and raise 11 children.

History of Redemption, notebook by Jonathan Edwards – Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

As Advocate of Great Awakening, Edwards Stirs Debate

After completing his baccalaureate work at Yale College, Edwards began graduate studies. During this period, he preached for a short time to a small Presbyterian congregation in New York City. Upon completing his master’s degree in 1723, Edwards, through the machinations of his father, became the pastor of the newly formed church in Bolton, Connecticut. The town was a small agricultural community and suited neither Edwards’ ambitions nor, apparently, his idea of a harmonious church. He quickly left this post to become a tutor at Yale College, where he served for two years. Here, Edwards had the opportunity to arrange and plunge into the college library, which included sizable donations of titles from England. He also preached occasionally for the church in Glastonbury.

In 1726, Edwards was called to Northampton as an assistant to his grandfather, the Reverend Solomon Stoddard, and upon Stoddard’s death three years later became senior minister. During his time in Northampton, Edwards established himself as a revivalist, theologian, and member of the transatlantic evangelical network. He frequently returned to Connecticut, however, to visit family at Windsor Farms and elsewhere. He also came in professional capacities, as a preacher and ecclesiastical advisor, mostly in the context of the Great Awakening. In October 1740, when the famous itinerant preacher George Whitefield was visiting New England, Edwards conducted him from Northampton to his father’s house in Windsor Farms. It was as an invited guest preacher that Edwards delivered what has become the most famous sermon in US history, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” in July 1741 in Enfield (then a part of Massachusetts but transferred in 1749 to Connecticut).

Edwards’ involvement in the Great Awakening, and his role as an apologist for it as “a work of the Spirit of God,” embroiled him in controversy. The revivals had caused a split between supporters and opponents, known, respectively, as New Lights and Old Lights. Yale College had in 1741 denounced not only Whitefield but also the revivals generally. In September of that year Yale College asked Edwards to deliver the commencement address hoping he would be similarly dismissive. Instead, his address, “The Distinguishing Marks of the Work of the Spirit of God,” criticized those who failed to support the revivals.

Extremes within Movement Prompt Reassessment

One of the most controversial aspects of the Great Awakening was when itinerant New Light preachers declared that other ministers were unconverted and therefore not worthy of their office. Perhaps the wildest of the New Lights was James Davenport, a New Haven native who was pastor of a church in Long Island and made preaching tours through Connecticut. Typically, he would walk through the streets of a town, head thrown back, shouting at the top of his lungs. In early 1743, in New London, he even supervised bonfires of the vanities, during which he exhorted townspeople to burn books and clothes.

It was as the head of a council of ministers to curb Davenport that Edwards traveled to New London in March 1743. Shortly thereafter, Davenport recanted his activities and views. Reflecting on episodes such as these, and within his own church, Edwards went on to write A Treatise Concerning Religious Affections (1746), in which he delineated the negative and positive “signs” of true vs. counterfeit religion.

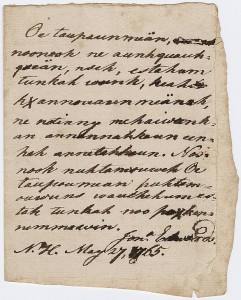

Prayer, in Mahican by Jonathan Edwards, 1764 – Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Edwards’ Writings Influence 19th-century Reformers

After his dismissal from Northampton, Edwards cast about for a new post. He candidated at the backwoods hamlet of Canaan, Connecticut, preaching there in late 1750 and early 1751. Ultimately, however, he settled on the mission at Stockbridge, where he served the Mahicans and Mohawks living there, as well as a small English congregation. Edwards had been involved in the founding of the Stockbridge mission in the 1730s and had been an admirer of David Brainerd, a missionary to Indigenous people in New Jersey. As a student at Yale, Brainerd had been expelled for criticizing the spiritual state of one of the tutors. Edwards had supported Brainerd and opened his home to him, where he died of tuberculosis in 1747.

Even more, Edwards published Brainerd’s diary, The Life of David Brainerd (1749), which became a standard work for missionaries in the centuries following. It was in Stockbridge, however, that Edwards wrote many of the treatises—Freedom of the Will (1754), Original Sin (1758), The End for Which God Created the World, and The Nature of True Virtue (the latter two works published posthumously in 1765)—that secured his fame.

After his death, Edwards’ life and writings exercised a profound influence on American religious life. In western Connecticut in particular, many of the pulpits were filled by “New Divinity” men, preachers who adhered to Edwards’ views. A key figure was one of Edwards’ students, Joseph Bellamy, pastor of Bethlehem, who maintained a school for boys and young ministers-in-training in his home. Edwards’ thought was instrumental in 19th-century reform movements, such as the abolition of slavery. Though a slaveholder and defender of slavery himself, Edwards’ ethical thought was transformed by another of his disciples, Samuel Hopkins, into abolitionism that took early root in the late 1700s on into the 1800s. Through Bellamy, Hopkins, and many other followers, including Edwards own son, Jonathan Edwards, Jr., the culture of Connecticut was deeply influenced by Edwards well into the 19th century.

Kenneth P. Minkema, PhD, is the Executive Editor of The Works of Jonathan Edwards and of the Jonathan Edwards Center & Online Archive at Yale University.