By Peter P. Hinks

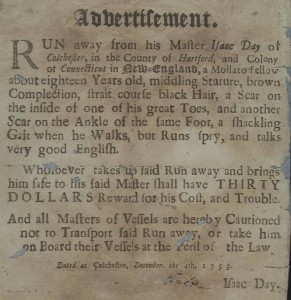

Advertisement for a runaway slave, 1753 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Illustrated

The American Revolution espoused great democratic ideals: liberty, equality, freedom for self, and national rule. These ideals helped inspire the anti-slavery sentiment that emerged during this era. White Patriots argued that the British intended to tyrannize the colonists so brutally that they would reduce them to the status of slaves, and they pointed to the black slaves in their midst to illustrate vividly what the British might do to white Americans. Some, however, became concerned that their own denunciations of tyranny and slavery rendered them hypocrites because they continued to enslave thousands of Africans and African Americans.

As one anxious Connecticut author wrote before 1775, “How can we expect our endeavors at the court of Great-Britain should be bless’d, when we are acting a more cruel part with our neighbours, the blacks?” While slavery remained in place throughout the Revolution in Connecticut, more white patriots grew troubled by the contradiction between their professed ideals and the slavery that existed all around them.

The Influential Speak Out against Slavery

The most important white critics of slavery to emerge in Connecticut during the years of the American Revolution were Congregational ministers Levi Hart and Jonathan Edwards, Jr. Both men were strongly influenced by Congregational minister Samuel Hopkins, who lived in Newport, Rhode Island. Newport was one of the most important centers in North America for the Atlantic slave trade. Hopkins witnessed at first hand the brutalities of this traffic while a minister there and was deeply disturbed by this commerce. In 1775, he exhorted Americans to abandon the sinful traffic or, he prophesied, an angry God would frustrate their movement for independence. Hopkins’s words helped move the colonies in New England and beyond to end the importation of Africans.

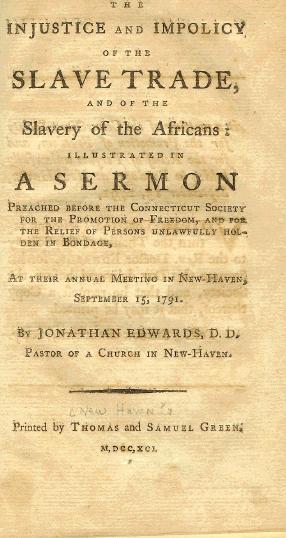

A printed sermon by Jonathan Edwards Jr., 1791

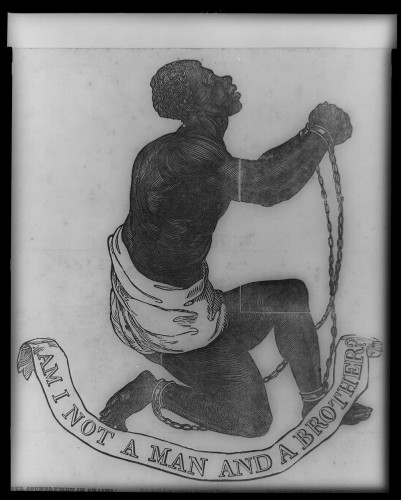

Reverend Hopkins also argued that the institution of slavery itself was sinful and should be abolished, contending that the highest calling of a Christian was to love others without any self interest, a grace from God that he called “disinterested benevolence.” All humans, regardless of how seemingly foreign or inferior, were, in truth, “neighbors” who merited this love and fellowship. For Hopkins, nothing more grossly violated this central Christian doctrine than slavery, which reduced one group to outsiders to whom benevolence and fellowship did not apply. People of African descent, he admonished, were the colonists’ brothers and sisters whom God valued as much as whites. Although whites might perceive slaves as being ignorant and degraded, he said, it was only because enslavement had made them so. Because colonists had exploited the enslaved, they now had a Christian obligation to free, uplift, and enlighten those held in bondage.

Hopkins, Edwards, and Hart all believed that the position the patriots adopted on slavery would deeply affect the course of the Revolution. They argued that the new nation as a whole must strive to rid itself of a sin as horrible as slavery or else God might condemn them to defeat and enslavement by the British. While the foundation of their repudiation of slavery was religious, they believed the Revolution was in accord with their faith and deeply valued its dedication to individual freedom and representative government. Levi Hart wrote one of America’s first proposals for the emancipation of the slaves, Liberty Described and Recommended, with the hope that it would be adopted in Connecticut and launch the new nation on the path toward total abolition.

The Connecticut Society for the Promotion of Freedom

While this plan was never adopted by the state, it did pass gradual emancipation laws in 1784. These did not, however, spell an immediate end to slavery—or its effects. Accordingly, Hart, Edwards, and other ministers and influential white men opposed to slavery formed the Connecticut Society for the Promotion of Freedom and the Relief of Persons Unlawfully Holden in Bondage in 1790. In 1794, the society vigorously promoted a bill for the total abolition of slavery in the state, and it came very close to passage. Nevertheless, the society devoted itself throughout the decade to assisting aggrieved blacks—free and enslaved—in the courts and to fighting the terrible threat blacks faced from kidnapping. The society’s work signaled the gradual demise of slavery in the state.

Outrage with slavery in Connecticut in the late 18th century sometimes became so fierce that it moved toward violence. In April 1792, three black men from Cheshire armed themselves and went to a house in Wethersfield, determined to retrieve a daughter who had been forcibly kidnapped in Cheshire and claimed as the slave of John Robbins. The three men succeeded and attorneys from the Connecticut Society defended them in court.

Kidnapping remained a serious threat for African Americans in Connecticut and nowhere more so than in Fairfield County, which was close to New York where slavery remained fully legal. Support for slavery remained stronger in Fairfield County than in any other county in the state. In 1790, 795 slaves remained in the county, nearly one-third of all the slaves in the state. Numerous owners in that county illegally removed enslaved children and adults to New York and further south.

Very few whites in the county troubled their consciences with this crime, but Isaac Hilliard of Redding was a notable exception. In the 1790s, at great expense to himself and acutely contrary to local sentiments, he successfully sued several men in Redding and Newtown for kidnapping. He said to the kidnappers, “Why do you not come out fair, and show your cloven feet, and say you wish to see your fellow creatures stolen and sold?” The Connecticut Society also assisted in retrieving blacks illegally sold to southern owners as slaves. These defenses of aggrieved African Americans were an important expression of anti-slavery in the state in the late 18th century.

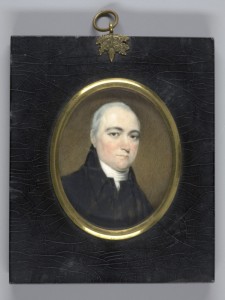

William Dunlap, Timothy Dwight, ca. 1813, watercolor on ivory – Yale University Art Gallery

The Fight Continues into a New Century

In the years after the Revolution, some whites welcomed the prospect of an expanding black freedom and the eventual inclusion of African Americans into the nation as citizens. The members of the Connecticut Society for the Promotion of Freedom along with other similar state societies proclaimed in 1794 that we “must prepare them for becoming good citizens of the United States, a privilege and elevation to which we look forward with pleasure, and which we believe can be best merited by habits of industry and virtue.” The members of this elite society, which included Timothy Dwight, his brother Theodore, the jurist David Daggett, United States Congressman William Hillhouse, and the prominent attorney and United States Congressman Simeon Baldwin, were some of the wealthiest and most influential men in the state.

Even though the Connecticut Society had disappeared by 1800, these men carried their convictions into the new century. In 1804, James Hillhouse, who had risen to senator, was among a handful of legislators who fought ardently to bar slavery from the recently acquired Louisiana Territory. Hillhouse alone, however, did so by affirming the essential humanity and equality of blacks with whites.

The voices of these influential men helped uphold the vision of a broader black freedom for the white populace of the state, especially given the relative weakness of blacks’ own political voice at the time. Dwight, a theologian and president of Yale College, particularly argued that whites’ gross exploitation of blacks during slavery had now imposed an unavoidable Christian obligation upon them to reach out to blacks as fellow humans and help them overcome the damage and disadvantages wrought upon them by slavery.

Peter P. Hinks is a historian who has researched and written extensively on slavery and black freedom in Connecticut and the American North.