By Gregg Mangan

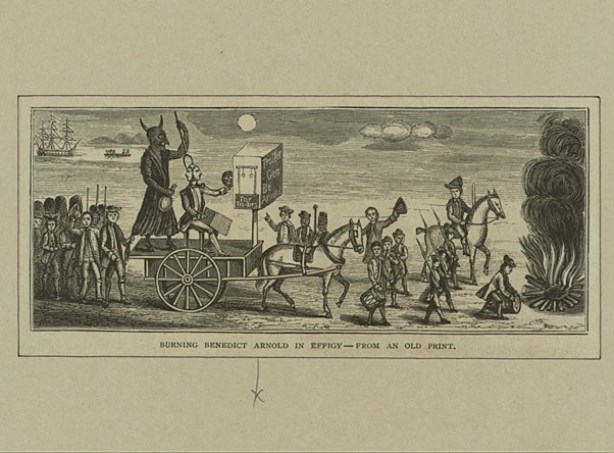

Benedict Arnold, despite the extraordinary efforts and sacrifices he made on behalf of American independence, is probably known best for being a traitor. In the middle of the Revolutionary War, he changed sides, abandoning the Americans’ fight for independence in return for the military rank and financial reward he received in the British army. Prior to his treason, however, Arnold compiled an impressive string of accomplishments on behalf of the colonial cause. His treason is so well known, in part, because of his bravery and meritorious service to the Continental army in the early years of the war.

The Arnold Family in Connecticut

Birthplace of Benedict Arnold, Norwich, ca. 1851 – Connecticut Historical Society

Arnold came from a proud background. His great-great grandfather was one of the founders of Rhode Island, and his great-grandfather Benedict won election as governor of Rhode Island five times. When his father Benedict Arnold III, a cooper, moved to Norwich, Connecticut, in 1730, he married Hannah Waterman King, the daughter of one of the town’s founders.

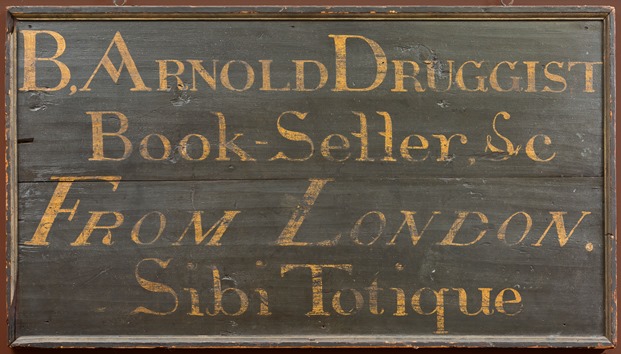

Benedict was born in Norwich on January 14, 1741—one of only two of his parents’ six children to survive childhood. He was a bold, fearless child who enjoyed physical activity. He received a good education in his early years, but left school at fourteen when his father began drinking heavily after the collapse of the family business. Arnold then apprenticed himself to a cousin who was an apothecary (an early word for a pharmacist or druggist) in Norwich, but soon ran away to fight in the French and Indian War. His mother died in 1758 followed by his father in 1761, at which point Arnold moved to New Haven and set up a store that sold books, drugs, and jewelry near Yale College.

Benedict Arnold’s shop sign from George Street, New Haven, ca. 1760 – New Haven Museum

Revolutionary War Hero

While in New Haven, Arnold met his first wife, Margaret Mansfield. They married on February 22, 1767, and had three children. Arnold became a shrewd and prosperous trader in New Haven while also joining the local militia in 1774 and being named its captain soon thereafter. In April of 1775, after learning about the conflicts at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, Arnold organized his men in preparation for a march to Cambridge to aid in the fight against the British.

After witnessing just how little firepower the colonials possessed in Cambridge, Arnold launched an attack to capture British artillery at Fort Ticonderoga on May 10, 1775. The attack was a success, despite Arnold’s conflicts with Vermont folk hero Ethan Allen over command of the assault.

The following fall, Arnold led a grueling march through the Maine wilderness in an attempt to capture the Canadian city of Quebec. The attack, on the final day of the year, ultimately failed and Arnold received a debilitating wound to his left leg. After recuperating, he spent the remainder of 1776 withdrawing from Canada while preventing the British from advancing down the Hudson River.

On April 27, 1777, Arnold confronted British forces under former New York governor William Tryon in Ridgefield. Tryon’s forces, after burning the town of Danbury, headed back toward their ships in Long Island Sound when Arnold mounted an attack in which a witness later claimed Arnold “exhibited the greatest marks of bravery, coolness, and fortitude.” Arnold had a horse shot out from under him and repeatedly exposed himself to fire, but despite his bravery, proved unable to cut off the British withdrawal.

Colonel Arnold – New York Public Library Digital Collections, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs

The Battle of Saratoga

Perhaps Benedict Arnold’s greatest military achievement came later that fall in two conflicts (on September 19 and October 7, 1777) referred to as the Battle of Saratoga. Once again Arnold’s propensity for action led him into the thick of the battle where he received a wound in the same leg injured in Quebec, but not before he helped rally troops in defeat of General John Burgoyne’s British forces as they attempted to sever New England from the rest of the colonies. The victories at Saratoga influenced the French decision to join the war against the British.

With his mobility significantly impaired by his shattered left leg —physicians at Saratoga wanted to amputate it, but Arnold refused and later suffered horrific infections and terrible pain—he requested an appointment as military commander of the city of Philadelphia in June of 1778. While there, colonists accused him of engaging in profiteering and socializing with Americans loyal to Great Britain. One of these “Tories” was Margaret (“Peggy”) Shippen, the woman who became Arnold’s second wife in April 1779.

Arnold Commits Treason

Years of dedication to the patriot cause led to little recognition or reward for Arnold. He never received appropriate credit for his actions at Ticonderoga or Saratoga, the Continental Congress repeatedly overlooked him for promotion, and his temper and confrontational style made him many enemies in the army. In addition to being brave and hotheaded, Arnold often succumbed to vanity and greed. All of these factors may have played a part in his decision to commit treason. Charged with corruption during his military command of Philadelphia and facing a court-martial, Arnold, through his wife, contacted the British command with an offer to turn the strategically valuable Hudson River defenses at West Point over to the British in return for money and designation as an officer in the British army.

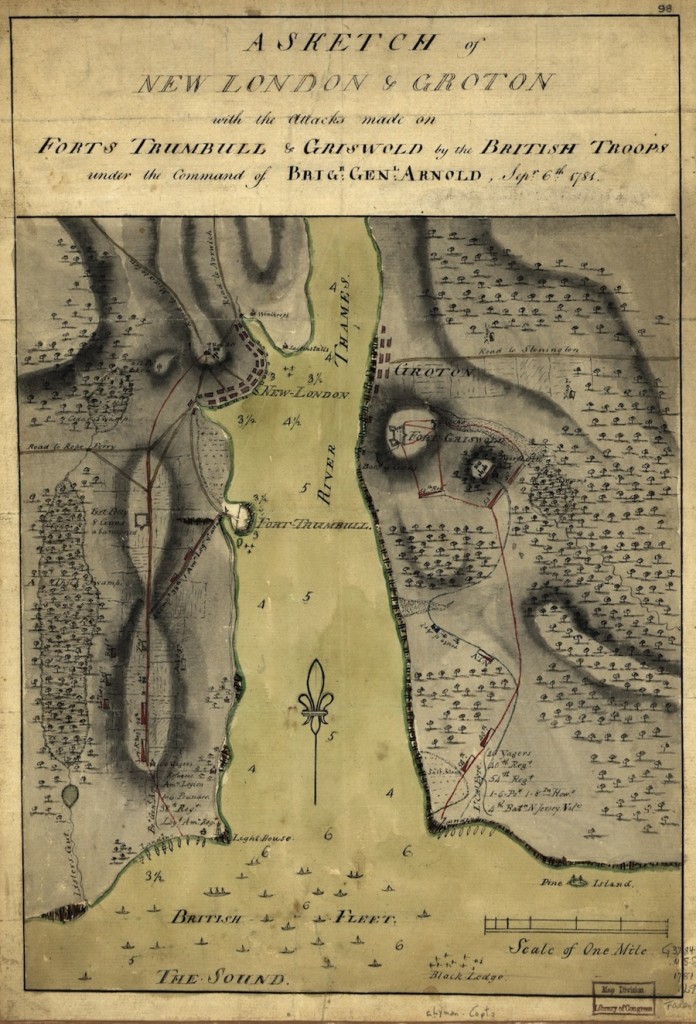

A sketch of New London & Groton with the attacks made on Forts Trumbull & Griswold by the British troops under the command of Brigr. Genl. Arnold, Sept. 6th, 1781 – Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

Benedict Arnold requested and received command of West Point from Commander-in-Chief, George Washington. He arrived there on August 5, 1780, and proceeded to weaken the garrison while feeding vital logistical information to the British. Colonial authorities accidentally uncovered Arnold’s treasonous plan after capturing British Major John André, fresh from a meeting with Arnold and in possession of the plans for West Point. Before word of the treason reached George Washington (who was on his way to visit Arnold at West Point), Arnold managed to escape to the British warship Vulture and begin his new life as a brigadier general in the British army.

A British Commander and Citizen

After joining the British army, Arnold saw limited action, mostly leading raids along the Virginia and Connecticut coasts. Arnold led a raid on the town of New London on September 6, 1781, that destroyed a number of privateering ships and colonial stores, but the burning of the town and the killing of surrendering Continental soldiers further damaged Arnold’s reputation.

Arnold set sail for England with Peggy after British general Lord Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, Virginia, on October 19, 1781. He returned to North America in 1785, seeking to establish a business in New Brunswick. His wife and children joined him in 1787, but a fire the following year destroyed his business. The family returned to England in 1791. Arnold spent his remaining years living on a modest pension and repeatedly petitioning the British government for additional funds and military appointments. He died in relative obscurity in London on June 14, 1801.

Gregg Mangan is an author and historian who holds a PhD in public history from Arizona State University.