By Steve Grant

Artist, author, and influential conservationist Roger Tory Peterson pioneered the modern age of bird watching with his breakthrough 1934 book, A Field Guide to the Birds. Until Peterson came along, field guides were largely the work of ornithologists whose highly technical descriptions were only marginally helpful to the small numbers of recreational birders at the time. Suddenly, with Peterson’s book, birders, as they have come to be known, had clear, useful images, with arrows pointing to the distinguishing feature or features of each species, painstakingly painted by the author. Even with the country deep in the Great Depression, that first printing of Peterson’s book sold out in days.

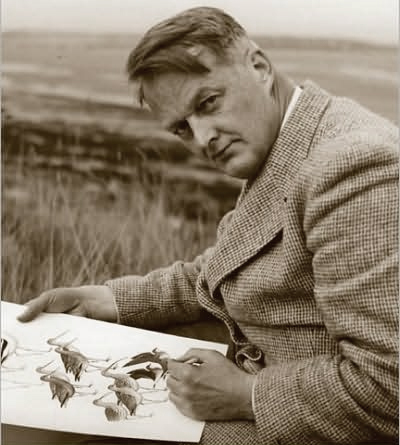

Peterson was born in Jamestown, NY, on August 28, 1908, a child of Charles Gustav Peterson and Henrietta Bader Peterson. He spent his young adult years in New England and New York City, and in 1954 Peterson moved to a home beside the Connecticut River in Old Lyme, where he lived for 42 years until his death at age 87 in 1996. “I’m basically a teacher,” he told an interviewer four years before his death. “I like to think of myself as an artist and a teacher. A teacher who uses visual methods, not the academic kind. My background is not that basically of a teacher, it is that of an artist.”

A Fascination with Birds

Roger Tory Peterson

Peterson often recalled an experience at age 11 that sparked his lifelong love of birds. While walking with a friend in Jamestown, Peterson spotted what he thought was a clump of feathers in a tree, near the ground. It was a northern flicker, apparently tired from migration. “I poked it with my finger; instantly, this inert thing jerked its head around, looked at me wildly, then took off in a flash of gold. It was like resurrection. What had seemed dead was very much alive,” he said. “Ever since then, birds have seemed to me the most vivid expression of life.”

After high school, where he received top grades for art, history of art, and mechanical drawing, Peterson studied in New York City. He earned degrees from the Art Students League and the National Academy of Design. Over the decades he was awarded 23 honorary degrees from colleges and universities. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award, for his cultural contributions. He was twice nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, in 1983 and 1986, and was a finalist for the award the second time.

Peterson’s original birding guide led to a series of 53 field guides in his name, among them guides to trees, wildflowers, butterflies, and ferns, many of them hugely popular with a public increasingly interested in reconnecting with the natural world. The birding guide, in eastern and western editions, was revised repeatedly over the years, with Peterson repainting or adding species into the last decade of his life. More than 8 million copies of the bird guides alone have been sold. Peterson’s field guide illustrations, whether depicting birds at rest or in flight, are clear, spare, and helpful, paired with text that is to the point, useful, and charmingly apt. Peterson’s description of the chimney swift, for example, is not only memorable, but in five words makes identification easy for a novice bird watcher: “Like a cigar with wings.”

An avid and highly accomplished birder himself, Peterson traveled to all seven continents birding and photographing birds. He especially loved penguins. By the 1960s, Peterson was not only an established author but a conservation celebrity. His was one of the prominent voices that helped advance the environmental movement of the late-20th century.

“The philosophy that I have worked under most of my life is that the serious study of natural history is an activity which has far-reaching effects in every aspect of a person’s life,” he said in a 1987 address to the New York State legislature in Albany. “It ultimately makes people protective of the environment in a very committed way. It is my opinion that the study of natural history should be the primary avenue for creating environmentalists.”

Peterson Advocates for the Environment

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Peterson witnessed firsthand the devastating impact of the pesticide DDT on bird species, most notably the ospreys that bred in the lower Connecticut River near his house. He first noticed the numbers of newborn osprey were falling off, followed inevitably by a decline in adults. Because the pesticide interfered with reproduction, populations crashed. Meanwhile, Rachel Carson, a friend, wrote Silent Spring, a powerful volume that damned the use of the pesticide and become one of the most influential books of the 20th century by touching off a national debate and furthering the nascent environmental movement. At the invitation of US Senator Abraham A. Ribicoff, a Connecticut Democrat, Peterson testified before Congress, blaming DDT and related pesticides for massive mortality among bird species. Through the 1960s and into the 1970s, Peterson denounced what he saw as humankind’s degradation of the natural world.

While famous for his field guides and contributions to conservation causes, Peterson expressed frustration that he couldn’t find the time to dedicate himself to bird painting as fine art à la John James Audubon, one of his influences. “I have yet to prove myself with that,” he said at age 84, referring to fine art painting. “Like Charlie Chaplin always wanting to play drama instead of being a comedian, that is the direction I would like to be going.” While he wished he had spent more time on painting as art, he nonetheless produced many fine art images over the years, including owls, penguins, and bald eagles. Many of his signed prints sell in the thousands of dollars today.

Steve Grant is a longtime Connecticut journalist specializing in natural science, environmental, and outdoor recreation topics.