By Emma Wiley

Alan L. Hart was a 20th-century physician, radiologist, and author who pioneered the use of x-ray in early detection for tuberculosis. He spent the latter part of his career in Connecticut working for the state’s Tuberculosis Commission to expand public health screenings and services. Hart was also one of the first people to undergo gender affirmation surgery in the United States.

Hart did not self-identify as “transgender” because the term did not come into use until the 1960s. While social terms and concepts of gender shift and change over time, Alan Hart fits into a long, persistent history of trans and nonbinary people. After he transitioned in 1917, Hart had to fight gender discrimination and the constant risk of others questioning his gender or outing him to his patients and community.

Early Life and Transition

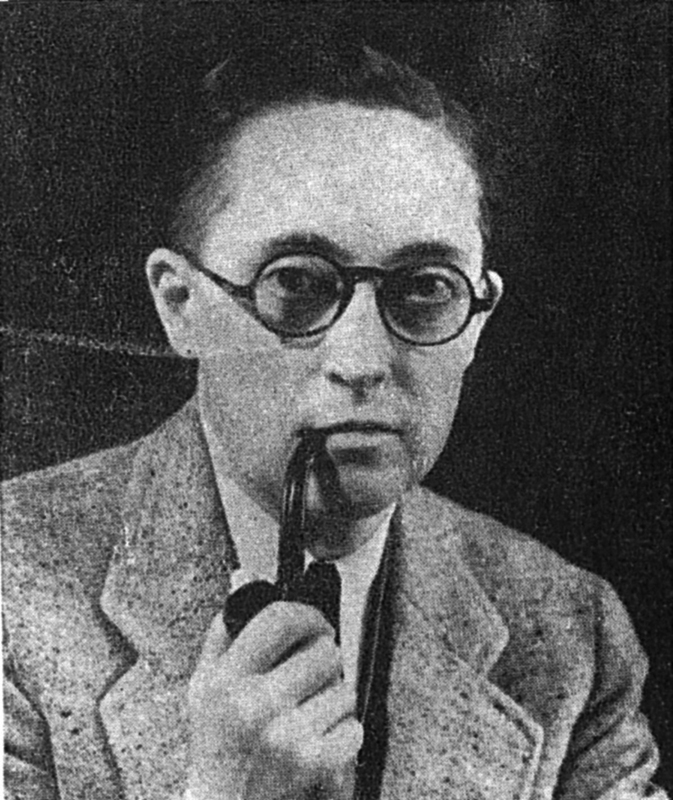

Hart (2nd from the right) in the Albany College Chemistry Laboratory – Dr. Alan L. Hart Collection, Lewis & Clark College Special Collections and Archives, Portland, Oregon

Assigned female at birth, Hart was born on October 4, 1890, in Halls Summit, Kansas, to Albert and Edna Hart. Hart spent most of his childhood growing up in Oregon, where he and his mother moved after his father died of typhoid in 1892. Described later in physician notes, Hart “regarded herself as a boy” throughout adolescence, preferring to dress in boy’s clothing and play the male role in games.

Hart attended and graduated from Albany College (now Lewis & Clark College); he also studied briefly at Stanford University during his undergraduate years. A few years later in 1917, Hart graduated with an MD from the University of Oregon Medical Department (now University of Oregon Health Services) with the highest standing in all departments.

Shortly after medical school, Hart sought treatment from Dr. Joshua Allen Gilbert for psychiatric guidance because according to Hart, “life had become so unbearable that I felt myself confronted by only two alternative courses—either to kill myself or refuse to live longer in my misfit role of a woman.” After hypnosis and psychotherapy did not help, Hart requested a hysterectomy (described by Hart and Gilbert at the time as a laparotomy) to stop menstruation and sterilize him. At the time, Hart’s rationale aligned with the dominant medical belief of the time—anyone with a gender identification that did not match the gender assigned at birth had a mental disease and should not reproduce.

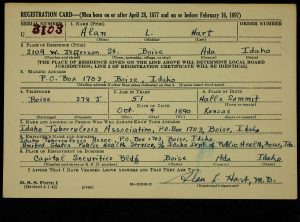

Following the hysterectomy, Hart cut his hair, wore men’s clothing, and adopted the name Alan. He married a woman (Inez Stark), registered for the military draft, and applied to physician positions as a man. A couple years later in 1920, Gilbert published his medical account of Hart’s transition in The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, taking care to protect “H’s” anonymity.

Facing Discrimination in the Medical Profession

Alan Hart Draft Registration Card, 1942 – Dr. Alan L. Hart Collection, Lewis & Clark College Special Collections and Archives, Portland, Oregon

As Hart tried to establish himself in the medical field, he faced discrimination and the persistent threat of being outed. In early February 1918, a former classmate recognized Hart and outed him to the San Francisco hospital where he was interning, forcing Hart to resign. Newspapers around the Northwest passed the story around, sensationalizing the “scandal” with headlines such as “Girl Posing as Male Doctor is Exposed.” Hart’s hometown newspaper, the Albany Daily Democrat, quoted him saying, “I have been happier since I made this change than I have ever been in my life, and I will continue to live this way as long as I live.”

While Hart did not back down from his transition, it was difficult for him to find hospital work. His family hired legal counsel in an attempt to get Hart’s name legally changed; the medical school, however, threatened to rescind Hart’s diploma and get him barred from practicing medicine. Constantly threatened with discrimination when his gender was questioned, Hart bounced around various physician positions across several states. Hart and Inez separated and eventually got divorced in 1925—Hart married a woman named Edna Ruddick later that year.

As Hart continued to build his medical career, he acquired a master’s degree in radiology from the University of Pennsylvania. Back in the West, Hart worked in Idaho and Washington, specifically treating and preventing tuberculosis patients. While the director of radiology at Tacoma General Hospital in Washington, Hart also began to publish novels—Doctor Mallory, The Undaunted, In The Lives of Men, and Dr. Findlay Sees It Through. Hart’s novels blended his professional and personal lives—they all revolved around themes of medicine and sexuality with loose autobiographical elements.

Hart’s Time in Connecticut

In the mid-1940s, Alan and Edna moved to Connecticut, eventually buying a home in West Hartford in 1950. Hart obtained a license to practice medicine in Connecticut in 1945 and earned a master’s degree in public health from Yale University in 1948. The couple spent the rest of their lives in Connecticut—Alan worked for the State Tuberculosis Commission and Edna was a social worker and an adjunct sociology professor at the University of Hartford.

As a common 20th century practice, newspapers—such as the Hartford Courant—regularly noted the couple’s social and professional activities. They publicized Alan’s public health programs and tuberculosis x-ray screenings and mentioned Edna’s attendance at social functions and charity events. Notably, the newspapers did not question Alan’s gender and often referred to Edna as “Mrs. Alan Hart.” After spending the last part of his life and career in Connecticut, Alan Hart died in Hartford at the age of 71 on July 1, 1962, from heart failure.

Hart’s Lasting Legacy

During the first half of the 20th century, tuberculosis—a highly infectious disease also known as TB or “consumption”—was one of the leading causes of death in the United States. Widely seen as a serious public health concern, Hart’s research and early use of radiology to detect tuberculosis allowed the infected to get earlier treatment and prevented many others from getting and spreading the disease. In his role as x-ray director of the State Health Department Office of Tuberculosis Control, Hospital Care and Rehabilitation, Hart hosted TB x-ray screenings and public education programs in Connecticut’s communities.

Even though Hart did ask his lawyer at the event of his death to destroy certain documentation of his life (including letters and photographs), a fair amount of historical sources about Hart’s life—both in his own words and in other’s words—remain extant. While contemporary early 20th-century newspapers reported on Hart’s transition—largely treating him as a curiosity and outing him to his community—in 1976, historian Jonathan Katz was the first scholar to connect Hart to the anonymous “H” referenced in Gilbert’s journal article. Despite gender-based discrimination, Dr. Alan Hart changed the medical field through his groundbreaking research and public health outreach.

Emma Wiley is the Digital Humanities Assistant at CT Humanities and holds a B.A. in history from Vassar College.