Located in the southwest corner of Southbury, nestled between Interstate 84 and the Pomperaug River, is a series of over 40 buildings that provide clues about the town’s role in a worldwide movement of the early 20th century. Following the outbreak of the Bolshevik Revolution, thousands of Russians fled to new lands to escape persecution. They set up thriving ethnic and artistic communities all over the world, including Southbury, Connecticut.

Authors Tolstoy and Grebenstchikoff Create a Place for Refugees

In 1917, the Bolshevik Revolution violently overthrew the government of Tsar Nicholas II in Russia. Politicians, lawyers, and military officers who remained loyal to the Tsar found themselves rapidly chased out of the Crimea, across Siberia, and eventually out of the country. These refugees went about setting up new ethnic communities across the globe.

In 1925, two Russian writers, Count Ilya Tolstoy (son of author Leo Tolstoy) and George Grebenstchikoff founded a community in Southbury meant to house Russians fleeing persecution. Tolstoy, who found the area first, fell in the love with the way the Connecticut hills reminded him of the Russian countryside and set up a home in Southbury in 1923.

St. Sergius Chapel, a rubblestone building with a gilded onion dome and a double Russian Orthodox cross – National Register of Historic Places

Grebenstchikoff purchased much of Tolstoy’s property in 1925, buying an additional 100 acres of property nearby the following year. He envisioned Southbury as a summer retreat for Russians living in New York and the surrounding area. It was customary in Russian culture during this time for the upper classes to have summer homes, but few immigrants could afford such luxuries on the salaries they drew after arriving in America.

Churaevka, a Haven for Russian Culture

Grebenstchikoff also envisioned his new settlement as a home for artists and writers. He wanted to create a cultural center for the development and dissemination of knowledge to enrich the lives of local residents. The village took the name “Churaevka” (a mythical Siberian village found in one of Grebenstchikoff’s stories).

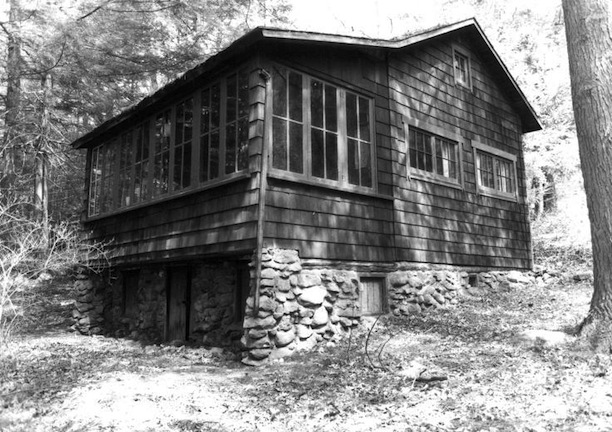

Soon musicians, writers, scientists, and artists all began moving to Southbury. The village had its own print shop and used it to help spread the influence of Russian culture. Among Churaevka’s most distinctive features, however, was the St. Sergius Chapel—an onion-domed church with a double Russian Orthodox cross—completed, in large part, with the help of generous donations from Igor Sikorsky.

Though Churaevka proved a haven for Russian exiles for the next several decades, the community never thrived the way Grebenstchikoff envisioned. Over the years, even Grebenstchikoff discovered he could not survive on a writer’s salary and he took a job teaching at Florida Southern College. The population at Churaevka remained largely Russian through most of the 20th century but became increasingly Americanized as years passed. The summer cottages became year-round homes and the artistic community became home to residents of all professions. Despite these changes, however, the unique blend of American and Russian architecture found in Churaevka, along with the important part the village played in defining early 20th-century Russian immigration, earned it a spot on the National Register of Historic Places in 1988.