By Kelly Marino

Lewis Dunham Brown and his son, Henry Lewis Brown, were pioneers in the US silk industry. Innovating new methods, the two men’s business became a force in silk production and helped improve silk manufacturing practices across the country. In Connecticut, they established factories in Mansfield and Middletown.

Family Ties to the Silk Industry

Lewis Dunham Brown was born to parents Selah and Elizabeth (Dunham) Brown from North Coventry, Connecticut, on April 10, 1814. Brown’s family made a living through farming, an endeavor he assumed for the first part of his life. Brown moved to Mansfield in 1837, where he later became involved in the town’s growing silk industry. On November 30, 1837, Brown married Asenath Augusta, daughter of James Royce. The couple had five children, including one son, Henry Lewis.

Connecticut had long-standing ties with the silk industry dating to the 1700s. By 1826, approximately three-out-of-four households in Mansfield raised silkworms. Mansfield was also the town where Rodney and Horace Hanks started one of the first silk mills in the United States in 1810. In the mid-1800s, however, experiments with a new type of mulberry tree, poor weather, and blight posed significant challenges.

While other silk businesses gave up or began importing raw silk from China, Japan, and Italy to use in production, Brown was just getting started. Both Brown and Asenath’s families had ties to local silk development. In 1850, Brown began his first silk business in Gurleyville (part of Mansfield) with his father-in-law, James Royce, who constructed the facility in 1848. Brown and Royce produced skein silk (wrapped bundles of silk) used in various projects.

In 1853, Brown bought another mill (one once owned by the Conant Brothers in Gurleyville) which he operated alone until 1865. As all accounts suggest, he was a respected owner with descriptions of Brown having “rugged energy and perseverance” and being “decided in his opinions.” In addition to being a businessperson, Brown helped with the development of the Center Cemetery and served as a selectman and on the local board of relief. He also supported the Methodist Episcopal and Congregational Churches.

In 1865, Brown sold his business in Gurleyville to William E. Williams, and he entered into a partnership with his son Henry. Operating as L. D. Brown & Son, they began business at the former William Atwood Mill in Atwoodville (also part of Mansfield), where they worked until 1871.

The same year he became business partners with Henry, Lewis Brown also purchased a large Greek Revival dwelling in Mansfield Center, constructed in 1836. Now known as the Edwin Fitch House (after the original architect/owner), the house was formerly owned by Edmund Golding, a fellow silk producer. The Brown family inhabited the lavish home for several decades. Brown, still passionate about agriculture, carefully maintained gardens with well-manicured flowers.

The New Middletown Mill

Interior of the former L.D. Brown & Son silk mill, now the site of Estate Treasures – Kelly Marino, used with permission.

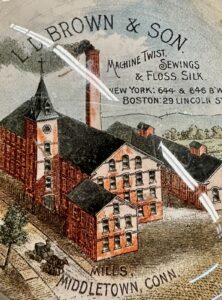

Following the Civil War, the South Farms area of Middletown experienced a new wave of industrial development. In 1871, Lewis and Henry Brown moved their business to Middletown and opened a new silk mill. The company started with a three-story brick building and expanded the next year to include a dye house and boiler plant. Around 1890, owners added a two-story office block and a one-story manufacturing block with a sawtooth roof for warping and weaving machines to produce new silk fabrics. A 50-horsepower steam engine fueled the mill, which processed about 35,000 pounds of raw material each year. Production involved reeling, spinning, doubling, twisting, and dyeing. The finished products then made their way to the company offices in Boston and New York City for selling.

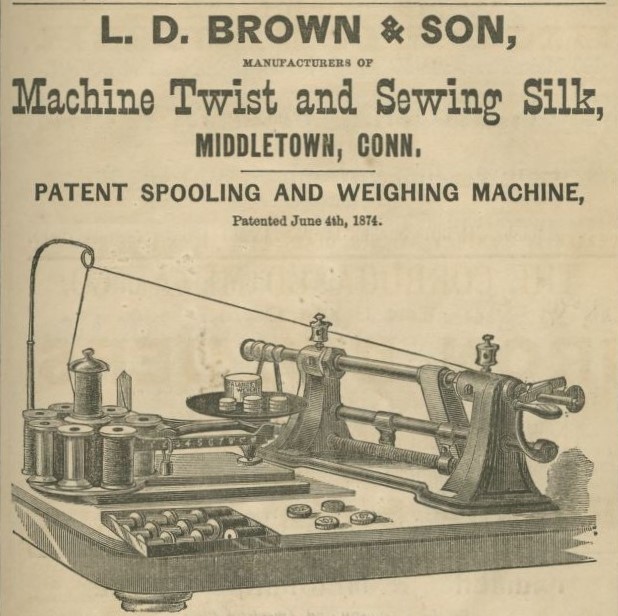

In Middletown, the mill produced machine twist and skein and spool sewing silk, which was lauded for high quality, being both durable and having pure dye. The Browns produced materials under several different brand names: L. D. Brown & Son, Middletown Mills, Paragon, and Connecticut Valley. Henry became famous for his patented innovations, including technology for improvements in winding soft silk and a new strategy for silk spooling and weighing. Lewis Brown died on November 21, 1883, leaving Henry to continue the business. Records suggest that the company peaked in 1884 with a record 150 workers, many of Irish American descent.

By 1903, L. D. Brown & Son Mill faced difficulties. That year, employees—under the direction of Richard Dempsey—formed a short-lived branch of the Silk Weavers Union, pushing for improved conditions. By this time, the silk manufacturing industry in Connecticut had dissipated significantly and businesses like the L. D. Brown & Son Mill struggled. Mill owners convinced a former Connecticut governor, Owen Vincent Coffin, and his son to enter a joint business venture with them to try to keep the mill afloat. In 1903, however, the two men declared bankruptcy, in part because of the failure of this endeavor. Sources describe the mill as “financially embarrassed, heavily indebted.” Entering receivership, the mill was auctioned off in 1904.

Property is Repurposed

Various companies soon took over the former buildings. From 1904 to 1917, other silk producers, such as the Merchants Silk Company and the Poidebard Silk Company, inhabited the facilities. Then, in 1917, the F. B. Burns Lace Manufacturing Company bought the property to use for creating laces, silk and cotton nets, curtains and accessories, and custom dye, bleach, and finish services. By 1924, the lace company had downsized and moved mostly into the sawtooth block. The Russell Manufacturing Company utilized the eastern facilities to produce braided goods. By 1935, the Colonial Lace Manufacturing Company replaced the Burns Company, and by 1950, the Wilcox Lace Corporation occupied the sawtooth block. In the mid-to-late 20th century, Middlesex Bag and Paper Company, Inc., operated in the eastern portion of the property.

Beginning in 1960, The Formatron Corporation, which produced beauty and barbershop equipment, took over the site for several decades, along with other small businesses, such as Middlesex Electric. Some of the original structures were demolished in 2011 and 2014 to make space for a parking lot. Plans to demolish more have yet to be executed, and Estate Treasures, a thrift shop and estate clearing service, continues its business in the main building, which dates from the 19th century.

Kelly Marino is an Associate Teaching Professor of History at Sacred Heart University.