By Nancy Finlay

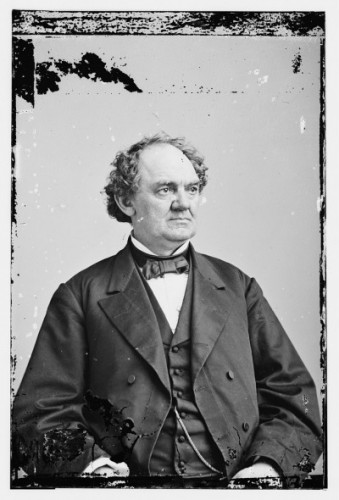

In 1879, P. T. Barnum, then serving as a Connecticut state senator, introduced a bill prohibiting the distribution of information on contraception and abortion, and the use of “any drug, medicine, article, or instrument” for the purpose of preventing conception. The great showman’s bill passed, becoming among the most restrictive birth control laws in the United States. Under the Barnum Act, married couples faced arrest and imprisonment for using birth control.

P. T. Barnum – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Used through Public Domain.

Though it remained on the books, authorities largely ignored the law until the middle of the 20th century. Many doctors quietly prescribed contraceptives for their patients, especially in those cases where pregnancy posed serious health risks. In the 1920s, the Connecticut Birth Control League began opening offices in the state and attempted to convince the state legislature to repeal the Barnum Act, which by that time seemed hopelessly out of date. The struggle went on for decades.

In 1950, Estelle Griswold and her husband, Richard, moved to New Haven and took up residence next to the offices of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut (PPLC). Griswold had been born in Hartford in 1900 and both she and her husband attended Hartford High School. Prior to relocating to New Haven, the Griswolds lived in Europe, where Richard worked for the State Department while Estelle engaged in humanitarian work. Once in New Haven, Richard went to work for an advertising agency and Estelle eventually became executive director of the PPLC. She continued the fight against the Barnum Act, and helped to stage “border runs,” taking women seeking information about birth control across state lines into New York and Rhode Island (where authorities made such information legally available).

Griswold v. Connecticut and the US Supreme Court

In 1960, the United States Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral contraceptive, making safe, effective birth control available—but not in Connecticut. The following year, Estelle Griswold and C. Lee Buxton, the Chair of the Yale Medical School’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and a volunteer with the PPLC, decided to challenge the Barnum Act in court. In a deliberate act of civil disobedience, they opened a small clinic near the PPLC office. The clinic immediately received numerous requests from married women seeking advice on birth control. Detectives also showed up promptly to ask questions and investigate. On November 9, 1961, authorities shut down the clinic just a few days after it opened. They arrested Griswold and Buxton, convicted them, and fined them $100 apiece. When the defendants appealed to the Connecticut Supreme Court, the court upheld their convictions. Estelle then appealed to the United States Supreme Court. Within Connecticut, the case became known as the “Buxton case,” but Estelle’s appeal to the nation’s highest court assured that it went down in legal history as Griswold v. Connecticut.

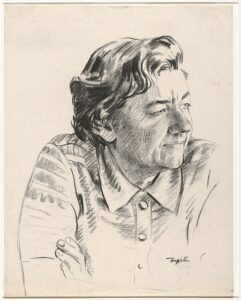

Sketch of Catherine G. Roraback, the attorney who represented Dr. C. Lee Buxton and Estelle Griswold in Griswold v. Connecticut – Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Used through a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

Although liberal members of the court found the Connecticut law “abhorrent [and] viciously evil,” the law did not immediately appear unconstitutional. Nevertheless, Justice William O. Douglas successfully argued that freedom of assembly, guaranteed by the First Amendment, along with freedom of speech, included all intimate and personal associations, and on June 7, 1965, the court voted 7-2 to strike down the Connecticut law. They ruled the Barnum Act unconstitutional and that an individual’s right to privacy was a fundamental right that could not be infringed upon by the state. While this initial decision applied only to married couples, in 1972 the court extended the same protection to unmarried couples.

The Supreme Court’s decision regarding individual rights in Griswold v. Connecticut had far reaching consequences. The ability to avoid unwanted births and to plan and space pregnancies improved the health of mothers and infants and helped make it easier for women to obtain better education and to pursue more challenging careers. The concept of the right to privacy benefited both men and women, who felt liberated to make their own decisions about their lifestyles without fear of persecution by the state.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.