By Nancy Finlay

He never lived in the Nathan Hale Homestead. There is no credible proof he ever said, “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.” The portrait of the handsome young spy that everyone knows is the invention of a 20th-century sculptor. So who was Nathan Hale?

Nathan Hale was born in Coventry on June 6, 1755. In 1773, he graduated Yale College and got a job as a schoolmaster in a small school in East Haddam. The following year he obtained a better position at a private academy in New London. One year later, the American Revolution began.

News of the battles of Lexington and Concord quickly reached Connecticut. Two of Hale’s brothers marched off to Massachusetts with the Connecticut militia; Hale himself enlisted a few weeks later, on July 6, 1775. By the time he joined Washington’s army in Cambridge, the Battle of Bunker Hill was over and the two armies were in a state of stalemate, which lasted until the British evacuated Boston in March 1776.

A Schoolteacher Becomes a Spy

Washington soon began transferring troops to New York, where he expected the next British attack to take place. The Battle of Brooklyn Heights at the end of August 1776 left the British in control of Long Island, with Washington and his army holed up in Manhattan and badly in need of reliable information about the opposing forces. Washington began recruiting spies. Although spying was not considered a very honorable occupation for a gentleman, Hale had been in the army for over a year and had yet to see any action. He decided to volunteer.

Hale left New York and traveled to Norwalk, Connecticut, where he arranged passage across Long Island Sound. He left his uniform, commission, and official papers behind in Norwalk, and, dressed as a schoolmaster in a plain brown suit and a round hat, landed in Huntington, Long Island. He should have made a convincing schoolmaster since he taught school for two years before joining the army, but he asked too many questions and soon aroused suspicion. In conversation with a British agent posing as an American sympathizer, he revealed his mission and British authorities promptly arrested him.

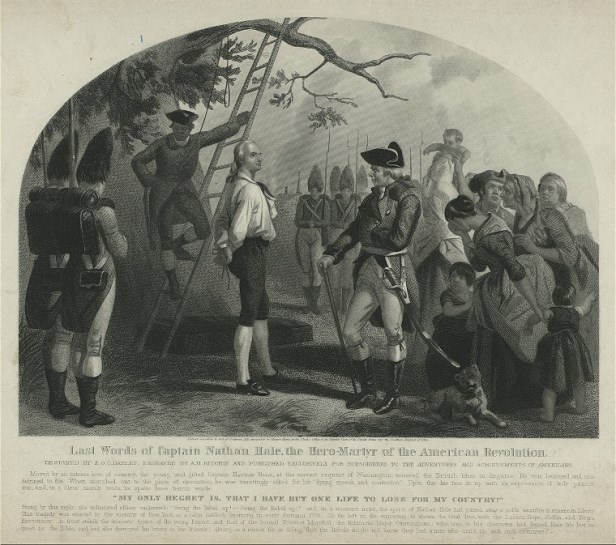

In the few days that Hale had been absent, Washington’s troops retreated again and the British occupied New York. Hale was brought to General Howe’s headquarters at what is now First Avenue and 51st Street, and promptly condemned to death. The following morning, September 22, he was taken to the artillery park at what is now Third Avenue and 66th Street and, after mounting a ladder, was hanged from a tree. The British buried his body nearby. Contemporary accounts indicate that he met his death with great resolution and composure.

Illustration of Nathan Hale approaching the British – From Life of Captain Nathan Hale, the Martyr Spy of the American Revolution by Isaac William Stuart, 1856, Library of Congress. Used through Public Domain.

How History Remembers Nathan Hale

Hale was not a very good spy, but he was a patriotic and likeable young man with many good friends who, over the years, kept his memory alive. It was one of his college friends who attributed to him his famous last words, “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.” The words are from Joseph Addison’s play Cato, and though the play was a favorite of Hale and his friends when at Yale, there is no reason to think that Hale spoke them at his execution.

Over the years, as his story was told and retold, history transformed Hale from an obscure and unsuccessful spy into a symbol of selfless sacrifice in the service of his country. Cities such as New Haven, Hartford, and New York erected statues of Hale. Since no contemporary likeness survived, the sculptors created idealized portraits of heroic young men. Perhaps the most famous of these statues is the one by Bela Lyon Pratt (1913) outside Connecticut Hall at Yale, where Hale lived as a student.

Nathan Hale Birthplace in Coventry, Taken in 2011 – Morrow Long, Flickr. Used through a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

Hale’s parents built what is now the Hale Homestead in Coventry in 1776, on the site of an earlier house where their son Nathan had been born. Antiquarian George Dudley Seymour acquired the house in the early 20th century and restored it as a shrine to Hale’s memory. Connecticut Landmarks acquired the property in the 1940s. In 1985, a vote by the Connecticut legislature officially designated Nathan Hale as Connecticut’s state hero.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.