By Steve Thornton

Father Leonard Tartaglia was sometimes called Hartford’s “Hoodlum Priest.” Like the 1961 film of the same name, Tartaglia ministered to the city’s poor and disenfranchised. He challenged institutional racism wherever he found it, in the state and in his own church. On March, 11, 1965, at the height of violent confrontations over civil rights in the South, Tartaglia and a handful of other clergy from New Haven and Waterbury headed for Selma, Alabama.

Father Tartaglia’s trip came in response to the vicious actions of Alabama authorities during their efforts to stop the 54-mile voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery by blocking the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The now-famous police response on March 7, 1965, resulted in Sheriff Jim Clark and a posse of deputies attacking 600 peaceful activists with clubs and tear gas on a day that became known as “Bloody Sunday.”

Connecticut Responds to James Reeb’s Death

On the same night that Tartaglia left for Selma, Unitarian minister James Reeb died from wounds received at the hands of a Selma lynch mob. Reeb had traveled from his Boston home to support voting rights marchers under attack in Alabama. The critically acclaimed motion picture Selma dramatizes his story.

Thousands of Connecticut people rallied and marched to mourn James Reeb’s death. At New Haven’s Woolsey Hall, 1,500 gathered to protest the murder. In Stamford, another 1,500 marched to the old town hall, demanding that President Lyndon Johnson take action to protect voting rights. In Norwalk, 700 people marched from the police station to city hall, challenging federal priorities that sent troops to Vietnam but none to protect civil rights workers. In Hartford, 350 gathered at the state capitol, while in Middletown, 300 demonstrators marched down Main Street singing, “We Shall Overcome.”

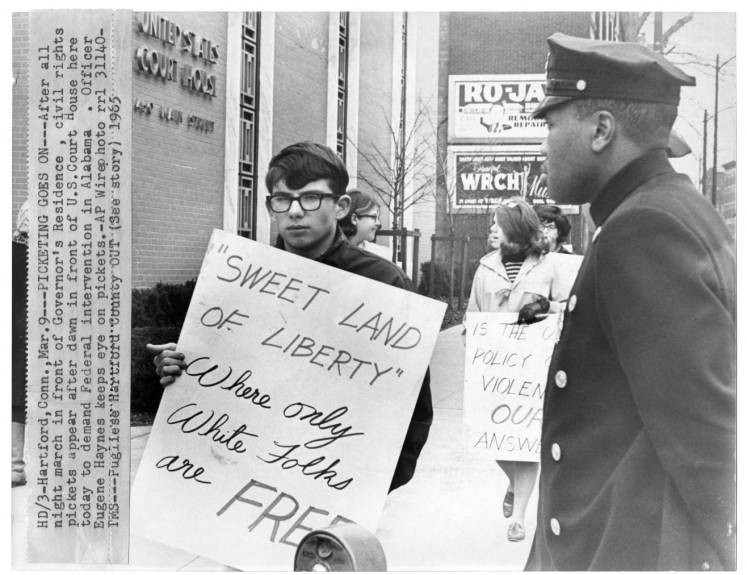

Civil Rights picket, US Courthouse, Hartford, March 9, 1965 – Hartford Times Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

Events in Montgomery, Alabama, Hit Home

While activists in Alabama made a second attempt to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge into Montgomery on March 9th, Hartford high school students and activists held a vigil at the governor’s residence to focus local attention on the Selma attacks. They brought legislative business to a standstill a short while later, simply by entering the state capitol, where an unusually large number of anxious police officers assembled to meet them.

Meanwhile, in Montgomery on March 25, a victorious rally of 25,000 people celebrated the third and final attempt to cross the bridge. Among them was the Reverend Richard Battles of Hartford who led 90 Connecticut residents in joining the southern march.

That same night, along Highway 80, the Ku Klux Klan assassinated Viola Liuzzo, a volunteer from Detroit who shuttled protestors between Selma and Montgomery. Reverend Richard Albin from the Greater Hartford Campus Ministry saw Liuzzo’s wrecked car as he rode a bus along the highway. Albin acted as security at the church that had been Liuzzo’s base. Exactly a week earlier—to the hour—a young black teacher from Hartford and her coworkers had been harassed and almost run off the same road, possibly by the same men.

Unsung Heroes

Most of the people who enlisted in the war against Jim Crow, like Father Tartaglia, never ended up in docudramas or history books. They were ordinary people, both black and white, who took extraordinary risks. Some of these lesser-known heroes include:

Civil Rights March on Washington, DC (Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Mathew Ahmann in a crowd), August 28, 1963 – National Archives

- Reverend Arthur L. Hardge, an African American minister from New Britain who joined the Freedom Riders in Florida in 1961 to test the federal law banning segregation at interstate bus facilities. Authorities convicted him and eight other clergy for “unlawful assembly” and sentenced them to 60 days in prison. After four days of lockup, and pressure from the ACLU, officials granted all nine protestors clemency.

- Seventy Yale students who traveled to Mississippi in October 1963 to assist a young African American who ran for Lt. Governor. They returned after the election with stories of bogus arrests and beatings.

- Elizabeth Faith Brown, a 44-year-old Salvation Army worker and UConn student who spent a week in a Florida jail in March 1964 on trespassing charges. Police arrested her and other Connecticut residents while they worked to desegregate a motel restaurant.

- In Voluntown, the Committee for Non Violent Action (CNVA) responded to the Selma call by sending 19-year old Peter Kellman. He worked behind the scenes, raising and lowering tents each day for the historic march from Selma to Montgomery. Peter stayed on after the march, building the Selma Free Library, registering voters, and organizing an alternative political party with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

The Legacy of the Voting Rights Act

Thanks, in part, to the protests and demonstrations in Alabama, legislators signed the Voting Rights Act into law on August 6, 1965, outlawing discriminatory voting practices in the United States. The act was amended many times, as several states—including Connecticut—found ways to sabotage the law’s intent. It was not until 1972 that Connecticut finally eliminated literacy tests and long residency requirements for voter registration.

In 2013, however, the US Supreme Court ended oversight of states that regularly violated the Voting Rights Act. Consequently, before the November 2014 elections, voter suppression initiatives in North Carolina, Kansas, Virginia, and Florida actually denied hundreds of thousands of registered voters “their basic right of citizenship,” according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

The presence of such controversies highlights the modern implications of the Selma story. As Father Tartaglia told an audience in 1966, despite years of progress, the challenge still remains to “reshape the community befitting the dignity of man.”

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project (shoeleatherhistoryproject.com)