By Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel

Mohegan history and religion have been preserved by many different voices in many different families through Mohegan Oral Tradition. However, since before the American Revolution, four women in particular have passed on Mohegan stories. Some of their lessons are very ancient. They are beyond time and exist only in memory. Brief biographies of these major women culture-keepers follow.

Martha Uncas

This great matriarch lived from 1761 to 1859. She was born into a difficult era following a tribal plague in 1755. Tribal records show two colonists named Daniel Leffingwell and Robert Allen—who claimed to be “well acquainted all along with the Indians since childhood”—wrote that “of late the number of the said Tribe has been very much diminished by a mortal sickness that came upon them.” At that time, 28 male heads of households were listed.

In 1774, tribal regent Zachary Johnson verified a tribal roster consisting of 14 “male heads of households” (or 26 including female heads). By 1799, Mohegan numbers were diminished by Samson Occum’s removal of the Mohegan Indians to Oneida Indian territory (in New York) and by the Revolutionary War. Records show Mohegan heads of households equaling 35 and the grand total of individuals numbered 84. However, when considering these numbers, it is important to note that many Mohegans were seamen, and their extended numbers are unknown.

Amidst all this, Martha Shantup Uncas fought for the demographic survival of her Nation. During the course of her life she had several husbands. Her men frequently moved away to look for work, hunt, or fight in wars. Some passed on at young ages. Regardless, she managed to raise numerous children who were descended from diverse tribal lines. Furthermore, she still found time to pass on traditional tribal lifeways to select Mohegans.

In keeping with Mohegan tradition, Martha taught her most important lessons only to two chosen protégés, one generation removed from her offspring: her granddaughter Fidelia A. Hoscott Fielding and grandniece Emma Baker. Mohegan Medicine Woman Gladys Tantaquidgeon explained how culture-keepers, like Martha, Fidelia, Emma, and herself, selected their students:

One thing I notice, that in connection with the Wigwam Brush Arbor Festival, my great aunt Emma Baker selected her niece Nettie Fowler, and I assisted her and I was her niece. So in later time, I worked as her Vice President [in the ladies’ Sewing Society]. Then it went from aunt to niece. That might hold true now…I might skip a generation.

Some of the tumultuous events of Martha’s life, including the birth of her seven children, are synthesized in the following description by her student Emma Baker:

Martha married [John] Uncas and had two children, Levi and Mary. Uncas got mad set the wigwam afire and ran away, was in the revolutionary war, was with Arnold, went to Canada; [I] have heard him tell me how much he suffered and one thing made me remember it. Mrs. Sigourney sent my brother a little book that had an account and scenes of different battles of the war and I remember one picture [where] in the background stood an Indian just ready to strike with his tomahawk and [I] always thought it was John Uncas. He was gone 20 years before he came to Mohegan. In the time Martha had a son by a Hoscott [named Samuel] and had married Bartholomew Tantaquidgeon and had two children, Nancy and Mary. After this she lived with [Gerdon] Wyyougs [a Pequot-Mohegan grandson of Samson Occum’s sister Sarah] who left a wife [Hannah Cooper] and had five children and in the sight of the smoke of the house, as the old squaws used to say, went and lived with Martha; she had two children Sarah [Fidelia Fielding’s mother ] and Charles Wyyougs.

Throughout her life, Martha was known for her sense of humor. For example, when asked to describe her first husband and those thereafter by her Non-Indian friend Frances Manwaring Caulkins (a historian from Norwich) Martha’s response was recorded as follows:

Oh it was so long ago. I have forgot his name, O he so handsome! his head was round like an apple and his neck like a gourd. My next husband, he handsome too and smart; all the squaws want to get away my two husbands. Then I marry Zachary and nobody trouble me; he so homely, all the Squaws let him alone.

In her later life, Martha married Arrowhamet/Zachary Johnson, a regent of the tribe. (Tribal records indicate that Zachary served as regent for Noah Uncas, the last hereditary Sachem of the Uncas family line.) The two of them are described as living atop Mohegan hill in Arthur Peale’s Uncas and the Mohegan Pequot (Boston: Meador, 1939), which quotes Reverend John Taylor, a Norwich rector, as observing:

On Mohegan Hill not far distant from the old fort of Uncas was the dwelling of Arrowhamet, the warrior, or Zachary, as he was familiarly called, that being his baptismal name. Tall, erect, and muscular, he seemed to defy the ravages of time, though it is recorded that several winters had passed over him. His wife Martha, who with him had embraced the Christian religion, was a descendent of the departed royalty of Mohegan… Zachary was arrayed with … [a] broad gold band, which had been the present of an officer as a testimony of valor, [it] was now constantly worn with his well-brushed hat, and old Martha arrayed every afternoon in a plain black silk gown in a very becoming manner… .

Today, the gravestones of Martha Uncas and her children Mary, Charles, and Sarah are still visible at Ashbow Burial Ground in Mohegan.

Jeets Bodernasha (Flying Bird)/Fidelia Fielding

The life of tribal culture-keeper Fidelia A. Hoscott Fielding bridged pre-reservation and post-reservation Mohegan society. She was born in 1827 and lived until 1908. Fidelia married William Fielding, and together they raised the offspring of her relative Effie Cooper. Fidelia’s grandmother, Martha Shantup Uncas, taught her to be the last fluent speaker of the Mohegan-Pequot dialect. Fidelia’s grandfather, Gerdon Wyyougs, was a Pequot.

Along with Emma Baker, Fielding served as a teacher to future Mohegan Medicine Woman Gladys Tantaquidgeon. In the following passage, Gladys remembers Fidelia:

Fidelia Fielding was the last speaker of our Mohegan-Pequot dialect…she and her grandmother Martha Uncas lived together and were said to have the Indian tongue used more than English…She lived about a mile east of our house. It was the last of the log houses on the reservation and she used to refer to it as a “tribe house”…She was what we would think of a true full blood Indian type. She was a little over five feet tall and a little bit on the medium build. She had jet black hair, black eyes, high cheekbones, and used to wear a calico dress and in cool weather she wore capes. She didn’t participate in Green Corn Festival [Mohegan Wigwam Celebrations] and meetings of the women in their [Church Sewing] society meeting. She was very much a loner, very much to herself. Fidelia was not pleased with non-Indian neighbors… I’ve heard that in several instances children in school were expected to learn English and forget all about their Indian cultural background, and if some of the older Indian women were speaking, like Fidelia, and some of the younger children appeared, they would cease talking because they didn’t want the children to be punished for learning the [Mohegan] language… It was she [Fidelia] who left [me] that very old belt that I wear with my Indian dress. It had belonged to her grandmother Martha Uncas.

Along with maintaining the tribal language, Fidelia learned traditionalist beliefs from Martha regarding the Makiawisug (Little People of the Woodlands).

Emma Baker

While Fidelia Fielding instilled fearful, xenophobic attitudes in her student, Gladys Tantaquidgeon, those negative notions were countered by the optimism and worldliness of Gladys’s other teacher, Emma Baker.

Emma lived from 1828 to 1916 and dominated the Mohegan cultural and political scene of the mid-19th to early 20th century. She served as Tribal Chair, Sunday School Superintendant of Mohegan Church, and Coordinator of the Church Ladies Sewing Society (which sponsored the Tribe’s annual Wigwam Festival). Non-Indians described her as “a very intelligent member of the Tribe” who “knew Latin.” She was married to a Mohegan man named Henry Baker and they had six children. Gladys described Emma as follows:

She influenced my life at that time in connection with “the ceremonial.” She was one of my grandfather [Eliphalet] Fielding’s sisters; [therefore] she was technically my aunt. [But] she was one of the women whom I used to refer to [respectfully] as “grandmother.”

Gladys Tantaquidgeon

Gladys Tantaquidgeon (1899-2005) began training with Medicine Woman Emma Baker as a specialist in herbal medicine in 1904. She recalls her early medicine teachings from Emma and two other spiritual “grandmothers” as follows:

My first trip out to the field, where medicine plants were growing, that would have been with grandmother Baker, grandma [Lydia] Fielding, and grandmother [Mercy Ann Nonesuch] Mathews. They were gathering them for winter use and at that time I would have been about five years of age … I think that it kindled a spark. Later on, I became interested in our Mohegan herbal remedies…here in my recollection, the women were the ones who gathered the plants and prepared the medicines.

From a fourth traditionalist “grandmother,” Fidelia Fielding, Gladys learned the sacred ways of the Makiawisug as a child. During her teens, Gladys expanded her education by touring New England with the family of anthropologist Dr. Frank G. Speck. Through that association, she met members of numerous related tribes.

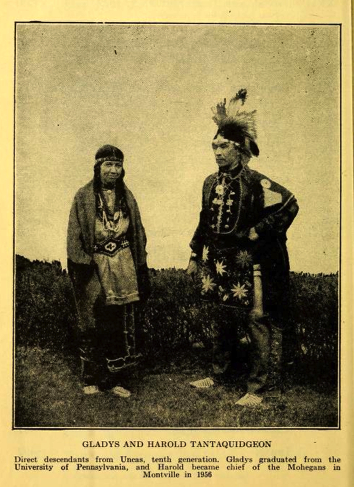

In 1919, she began studying anthropology with Speck at the University of Pennsylvania and, after completing her research there, she again visited among the northeastern tribes to conduct further field work. Then in 1934, she was hired by the Federal Government to administer new Indian educational privileges for Northeast tribes under the Wheeler-Howard Act.

Gladys made perhaps her greatest contribution in 1931 when she joined her father John and brother Harold in founding the Tantaquidgeon Indian Museum. That institution was created for the display of Native artifacts and the teaching of Mohegan culture. She worked there until 1935 when Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier offered her a position as a social worker on the Yangton Sioux reservation in South Dakota.

In 1938, Gladys transferred to the Federal Indian Arts and Crafts board to serve as a Native arts’ specialist under René d’Harnoncourt. Her duties included the supervision, teaching, exhibition, and sale of Native American artifacts from Montana to California. Gladys finally concluded her Government service in 1947 and returned to Mohegan Hill to become full-time curator of the Tantaquidgeon Indian Museum.

During the 1970s and early 1980s, Gladys was also Vice-Chair of the Mohegan Tribal Council. In the 1990s, her personal records—including correspondence regarding Mohegan births, graduations, marriages, and deaths—played a critical role in proving the Mohegan case for Federal Recognition, which was gained in 1994. She passed away at her home on Mohegan Hill in 2005 at the age of 106. In her lifetime she authored numerous articles on New England Indians and a book entitled Folk Medicine of the Delaware and Related Algonkian Indians (1942).

Through these tribal matriarchs, Mohegans enjoy an unbroken connection to their ancient lifeways, passing from Martha Uncas (1761-1859) to both Emma Baker (1828-1916) and Fidelia Fielding (1827-1908), then on to Gladys Tantaquidgeon (1899-2005) and continuing to the present day.

Mohegan Medicine Woman and Tribal Historian Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel holds an MA in history from the University of Connecticut Connecticut and an MFA in Creative Writing from Fairfield University; she has authored several books, including Medicine Trail: The Life and Lessons of Gladys Tantaquidgeon (University of Arizona Press, 2000) and Oracles: A Novel (University of New Mexico Press, 2004).

This article is excerpted from her book The Lasting of the Mohegans, Part I: The Story of the Wolf People (Uncasville: The Mohegan Tribe, 1992), which won the inaugural First Book Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas.