An Ivy league-educated anthropologist, Mohegan Medicine Woman Gladys Tantaquidgeon not only dedicated her life to perpetuating the beliefs and customs of her tribe for the generations who would follow, she also championed the protection of indigenous knowledge across the United States.

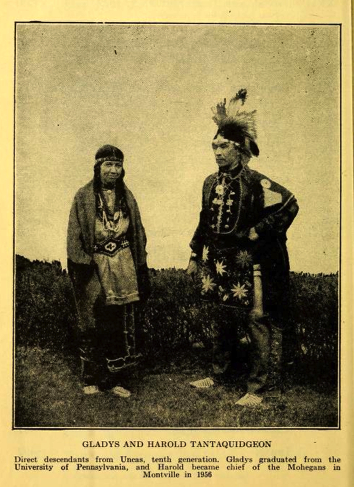

Tantaquidgeon’s lineage is traceable to Uncas, the famous 17th-century Mohegan Sachem who became a controversial figure in Native American history due to his collaboration with the English during the Pequot War. Despite the negative implications of an English alliance, Uncas was able to secure the safety of his people during a time when many tribes in New England were facing extinction. Three centuries later, his ninth-generation granddaughter found herself in similar circumstances. Born in a time that saw the closing of the frontier and the dissipation of tribal customs and knowledge, Tantaquidgeon’s training as only the third Mohegan Medicine Woman since the days of colonial America was essential to the survival of Mohegan culture.

The 19th-century Indian wars and anti-Native American policies of the United States government caused a disintegration of tribal practices, which Tantaquidgeon countered by becoming an activist not only for her own tribe but for other tribes across the nation as well. Recognizing the need for cultural preservation, the tribal nanus (elder women) began Tantaquidgeon’s training at age five in the medicine practices, sacred sites, and tribal history of her people. Tantaquidgeon would come to embody and perpetuate the Mohegan culture throughout the course of her life.

Her Life and Work

Gladys and Harold Tantaquidgeon

Tantaquidgeon was born June 15, 1899, on the Mohegan Reservation in Uncasville. During the early years of her life, she intermittently attended non-Indian schools but never graduated from high school. She entered the University of Pennsylvania at the age of 20 where, despite her lack of formal education, she studied anthropology under the renowned scholar Frank Speck.

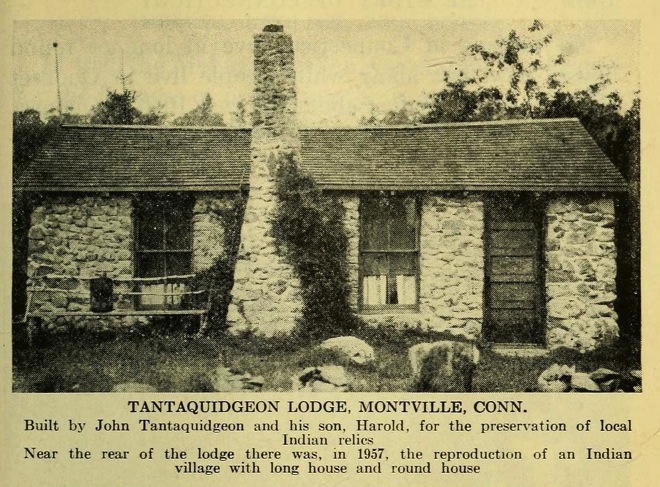

In 1942, Tantaquidgeon published A Study of Delaware Indian Medicine Practice and Folk Belief in which she documented the traditional practices and herbal medicine of coastal tribes of the East. Her efforts, as well as those of her father and brother, led to the creation of the Tantaquidgeon Indian Museum in Uncasville in 1931—which is today the oldest Indian-run and owned museum in the United States.

Tantaquidgeon also served the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs as a community worker on a Sioux reservation in South Dakota. Here, her efforts resulted in the promotion of Native American artwork as a method of preserving tribal autonomy. Native communities were able to benefit economically while encouraging the development of original Native American art. Ceremonial practices outlawed by the United States government were included in this art revival, and Tantaquidgeon’s efforts led to a reversal of the ban on centuries-old practices, such as the Sundance and the Raindance. Her experiences with reservation life on the Plains made her more conscious of the social issues women faced and this influenced her work as a librarian at the Niantic Women’s Prison during the 1940s.

Tantaquidgeon’s success in maintaining the records of her people has been cited as significant in the federal recognition of the Mohegan Tribe in 1994. Since 1960, only 8% of petitioning tribes have been awarded federal recognition, but Tantaquidgeon’s preservation of Mohegan documents, such as records of marriages, births, deaths, and graduations, provided evidence that helped the Mohegan Nation achieve that recognition. With federal recognition came the development of a diverse array of community resources, including the Mohegan Sun casino, the second largest casino in the world.

Gladys Tantaquidgeon received an honorary doctorate in 1987 from the University of Connecticut and another in 1994 from Yale University. In 1994 she was inducted into the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame. She died in 2005 at the age of 106.