By Jon E. Purmont for Connecticut Explored

When Giacomo (James) Tambussi, of Perleto, Italy and Maria Oliva of Voghera, Italy, the parents of Ella Tambussi Grasso, Connecticut’s first woman governor, arrived in Windsor Locks early in the 20th century, they followed tens of thousands of Europeans who immigrated to the United States in the decades after the Civil War. By 1910, 60 percent of the state’s population was first-or second-generation American, and Italian immigrants were the second largest group of new arrivals in the state behind the Irish.

James Tambussi journeyed to the New World in 1904 and Maria Oliva two years later. Both departed from Genoa and passed through Ellis Island before arriving in Connecticut to join family who had preceded them. Many years later Ella recalled a story her father often told. Like many other newly arrived immigrants he arrived in Hartford by boat from New York City with a “sign pinned on him” noting his destination-Windsor Locks, Connecticut. James Tambussi and Maria Oliva married in 1911 and remained respected members of the sizeable Italian contingent that settled in the small town north of Hartford.

Grasso’s Blue-Collar Roots

In a 1975 article for the New York Times Magazine Bernard Asbell described Windsor Locks as a “milieu of scant means and status but rich with striving and tradition.” In the early 20th century it was an industrial town where many immigrants found work in factories and mills. The town was a microcosm of Connecticut, reflecting the “melting pot” of newcomers seeking to adapt to American society and culture. Its small but expanding foreign-born population comprised not only Italians but also Irish, Poles, and those of other European nations. Yet like other Connecticut towns, Windsor Locks was a place where families knew one another, particularly immigrant families which frequently settled in neighborhoods populated by people they knew in the “old country.” Olive Street, where the Tambussi’s lived, was no exception since friends from their villages in Italy lived at both ends of the street. This environment planted in Ella a sense of community rooted in small neighborhoods filled with families not unlike her own, struggling and striving to achieve a better life for themselves.

Like many immigrants, Ella’s parents had limited schooling. Her father completed second grade and her mother finished grade six. His first job in Connecticut was as a machine operator at the Anchor Mill earning a dollar a day. He later worked at the General Electric plant in Windsor, and also at the Horton Chuck Company in Windsor Locks. Ella’s mother worked initially as an assembler in an electric motor shop; however, after Ella’s birth on May 10, 1919 she remained a homemaker. In later years Ella’s father and his brother Nate Tambussi owned and operated the Windsor Locks Bakery where they worked 12-hour nights, six days a week. While the Tambussi family story of hard work and struggle reflected the norm for immigrant families, one principle separated the Tambussis from many of their compatriots: they encouraged their daughter to aspire to an education. It was a goal, Ella later recalled, that her parents-particularly her mother, who had a passionate love for education-“could dare to dream.” Maria Tambussi nurtured her daughter’s love of reading, often buying her books including “department store markdowns and books in the five and ten cent stores.” Responding to a questionnaire sent to her by Family Circle Magazine in 1972, Ella recalled that from her mother she gained “a love of learning” and “a strong sense of duty and responsibility to my community.” Ella attended Saint Mary’s School in Windsor Locks (1925-1932) where she excelled at her studies. Her eighth grade teacher was Sister De Chantal, whom Ella described in a 1980 Connecticut Public Television interview as the “most remarkable woman I’ve ever met.” Sister De Chantal, Ella said, would tell “all the little kids that each of them had a very special gift and they had a special opportunity and there was one thing they could do better than anybody, and they had an obligation to develop that quality so that became part of my thinking.”

Education Opens New Vistas

The choice of Ella’s secondary school was largely her mother’s decision, and she chose the Chaffee School, a private, girls’ school in nearby Windsor. The neighboring Preli family’s daughter attended Chaffee, and Maria Tambussi wanted her daughter to have the same opportunity. Chaffee awarded Ella a scholarship and she entered the fashionable preparatory school in 1932.

Chaffee was a world quite separate from Ella’s blue-collar Windsor Locks upbringing. In his 1975 article Asbell declared that Chaffee was a “picture-book campus,” a prep school for exclusive private colleges that catered to the daughters of prominent and wealthy families. Ella blossomed there and achieved outstanding academic success. In addition to her studies she participated in a model League of Nations organization and the Drama Club. Ella said that Chaffee was an “awakening” which aroused interest in areas that she had not previously encountered. “I did not know the world of music (except Italian opera), art and theater until I went to prep school,” she explained in the Family Circle questionnaire.

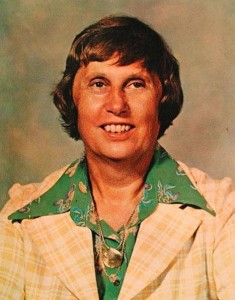

Yearbook portrait of Ella T. Grasso, class of 1940 – Mount Holyoke College

While Ella’s achievements at Chaffee enabled her to erase any doubts she may have had about her intellectual capability in the classroom, she remained the daughter of immigrants and thus apart from her socially prominent and economically well connected classmates. That social distance did not diminish her determination to continue on a road that would lead to invaluable educational opportunities and path-breaking experiences for this child of 20th-century pilgrims.

In 1936 Ella Tambussi entered Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts on scholarship. She enrolled in a new and experimental academic program called the “two-unit plan” and joined other young women specially selected for the program based on their intellectual aptitude, academic interests, and scholarly potential. Students in the program were expected to concentrate on two main subject areas. Ella chose economics and history and as a result came under the mentorship of Professor Amy Hewes. Professor Hewes chaired the department of economics and sociology and spearheaded the college’s adoption of the two-unit program. Hewes, whom Ella described as “one of the country’s most wonderful women,” had the most influence on Ella during her undergraduate and graduate years at Mount Holyoke.

Grasso’s Passion for Public Service Takes Shape

Amy Hewes was a skillful and admired teacher whose commitment to an active life of public service clearly distinguishes her as an important influence in Ella’s life. She was an advocate for labor reforms, particularly child labor and women’s rights in the workplace. Hewes’s scholarly achievements represented pioneering work by a woman scholar in the emerging fields of labor economics and statistical analysis. She is remembered as one of the first scholars to use “statistical measurements to better understand social phenomena.” And she believed in “strongly and conveyed to all,” noted Mount Holyoke alumna Catherine Roraback, “the equality of people and the excitement of fighting for a better society.”

Ella’s years at Mount Holyoke prepared her for what was to come in her public career. There is no question her intellectual horizons were nurtured by the stimulating and challenging academic environment at the college. Her eventual career in politics and government was in large measure instilled in her by the enlightened Mount Holyoke emphasis on public service, responsibility to others, and the influence of high achieving women among the college’s faculty. Ella’s rigorous academic schedule was supplemented by independent work. In an article she published in the Mount Holyoke Alumnae Quarterly in 1941, Ella recalled that she visited factories and met management people and “attended trade union meetings with workers.” In her free time Ella also worked as a volunteer at the Holyoke YWCA planning “educational and recreational projects with a group of industrial girls.”

The benefits that both the academic and practical education provided Ella included initiative and independence. She also observed the arduous, strenuous, and frequently unhealthy work that men and women engaged in at the textile mills of nearby Holyoke. That creative involvement invigorated her with a desire to improve the public good, and that desire became an integral part of the life of this young woman from Windsor Locks.

Ella’s research at Mount Holyoke culminated in a senior honors thesis under the supervision of Professor Hewes. Entitled “Workmen’s Compensation in the United States,” Ella’s study cited the need to establish compulsory state funding for workmen’s compensation and eliminate private insurance companies from covering workers. Also, she proposed a uniform workmen’s compensation law to fix “a virtual hodgepodge in which no progress toward standardization has been made.”

Ella Tambussi graduated from Mount Holyoke College Phi Beta Kappa and fifth in her class in June 1940. The intense studying, the opportunities to visit and observe industrial labor as well as savor the provocative and thoughtful words and ideas of the Mount Holyoke faculty provided Ella with an outstanding education and preparation for her life of public service. It was at Mount Holyoke that she set out to do all those great things which many aim to do in life. And it was from there she moved into the world of politics believing “in a very real sense of a relationship between politics and the lives of people-that what happens to us was affected by government and I wanted to be part of that government.

In a remarkable farewell letter to the Class of 1940, faculty member Jeanette Marks offered sage advice to the graduating seniors. Her letter, published June 10, 1940 in the student newspaper the Mount Holyoke News, reminded the graduates that there was for women “a greater opportunity to serve than women had ever known.” And in one memorable phrase that would resonate with Ella Tambussi, Marks urged the graduates to become “applied students of public affairs, refusing to use our influence by deputy.”

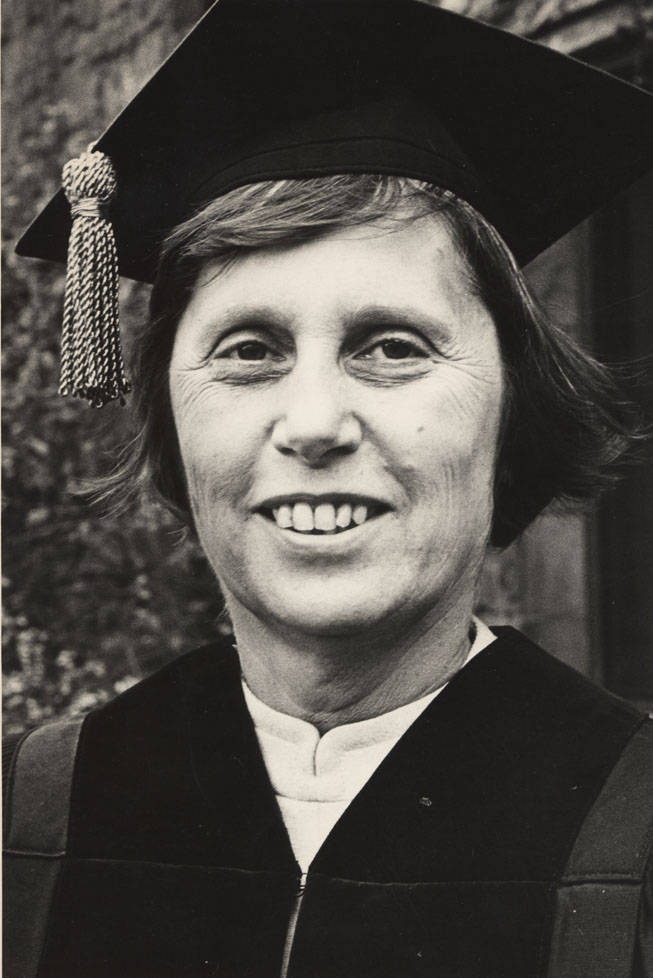

Ella T. Grasso receiving an honorary Doctor of Law degree, Mount Holyoke College, 1975 – Mount Holyoke College

Connecticut’s First Woman Governor

Thirty-five years later, Governor Ella Tambussi Grasso recalled Marks’s exhortation when she delivered the commencement address to the graduating class of 1975 at Mount Holyoke College. By then Ella’s career in public service, which culminated in her election the previous year as Connecticut’s first woman governor, more than lived up to the challenge she and her classmates were given back in 1940. In the commencement address Grasso looked back on her years at Mount Holyoke with great fondness. “I did all sorts of blissful things,” she said. “I was always taken seriously. I was encouraged to think of my life not as something that would happen to me, but as something that I would shape for myself. We were encouraged in the view that to share a passion for helping others was a joy and not drudgery.”

After graduation Ella remained at Mount Holyoke to pursue a masters degree in economics. She was Professor Hewes’s graduate assistant from 1940-42 and she wrote her graduate thesis on the history of the Knights of Labor under Hewes’s direction. Ella’s study of the 19th-century militant union analyzed the Knights’ role in American labor history.

In August 1942 Ella Tambussi married Thomas A. Grasso in St. Mary’s Church in Windsor Locks. Tom Grasso was a schoolteacher who years later became an elementary school principal in East Hartford. Ella’s first job, Interviewer Grade 1, for Connecticut’s State Employment Service was followed by a position as Assistant Director of Research for the War Manpower Commission in Hartford. She remained in state service until 1946 when she became a full-time homemaker and mother to her two children, Susane and James.

In 1952 Ella Grasso was elected state representative from Windsor Locks. It was the beginning of her 28-year career in elective public office. Early in her first term she caught the attention of Democratic State Chairman John M. Bailey who discovered her ability as a skillful legislator, writer, and researcher. The influential Bailey, who remained the state party chairman until his death in 1975, became Ella’s political mentor and adviser. From that vantage point in the legislature Ella began her long ascendancy to Connecticut’s highest elective state office.

Ella never lost an election. She served as secretary of the state from 1958-1970, and is credited with transforming the post into an activist office. She was elected congresswoman from the old Sixth Congressional District in 1970 and reelected in 1972. With her 1974 triumph over Republican candidate Congressman Robert Steele in the gubernatorial race she became the first woman elected state governor in her own right. A very popular governor, she was reelected in 1978, defeating Ronald Sarasin, but resigned the post in December 1980 for health reasons. Her resignation capped an illustrious career for a child of Italian immigrants whose parents “dared to dream” that their daughter would achieve success in this Land of Steady Habits. Ella Tambussi Grasso died of cancer on February 7, 1981.

Jon E. Purmont is Professor of History at Southern Connecticut State University and was administrative assistant to Governor Ella Grasso, 1979-1980.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 2/ No. 4 Aug/Sept/Oct 2004.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.