by Betty N. Hoffman, PhD

In its earliest years, Connecticut did not welcome Jews or, indeed, most Christians other than members of the Congregational Church. For nearly two centuries the Congregationalists controlled much of region’s religious, political, and social life, and the few Jews who settled in Connecticut did not form either a cohesive group nor establish permanent Jewish communities. Rather, they blended into the mainstream, frequently leaving their Jewish heritage behind.

German-speaking Jews Establish New Roots

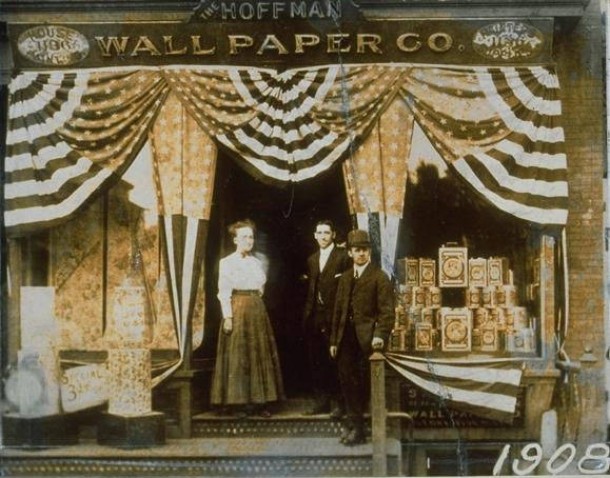

By the 1840s, as the control of the Congregational Church waned, the first permanent group of approximately 200 Jewish settlers established a community in Hartford. This group became the basis for the Jewish community of the present day. Coming primarily from Germany and Austria, they settled in the downtown area of Front, State, and Windsor Streets near the Connecticut River docks. They found work in diverse occupations, from cutting meat to repairing watches, to trading and teaching. Some founded their own businesses.

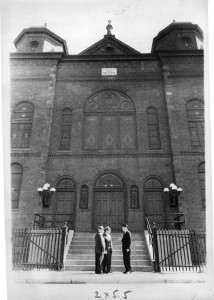

Ados Israel Synagogue, Hartford, 1961 – Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library and Connecticut History Illustrated

Forbidden by law to organize formal congregations, the first Jews worshiped in private homes. It was not until 1843 that groups from Hartford (Congregation Beth Israel) and New Haven (Mishkan Israel) successfully petitioned to have the laws changed to allow them the same religious rights as Christians.

Within a few years, the Hartford Jewish community boasted a rabbi, a hazzan (or cantor, a prayer leader, generally with a good singing voice), a shochet (a ritual slaughterer, trained in Jewish law, who certifies that the animal has been killed humanely and can be eaten), and a religious school. Members of the congregation also founded the Ararat Lodge, a chapter of the national fraternal order B’nai B’rith, for men and the Frauen Verein, later called the Deborah Society, for women. Not only did these groups provide places where the members could gather for social events based on the culture and language of the old country, but they were also charitable and service organizations.

As the Jewish community took root, its members encouraged family and friends to join them. By the early 1880s, the population of Hartford stood at about 50,000, with about 1,500 of these Jews. But, this would soon change.

The Second Wave of Jewish Immigration

The assassination of Russian Tsar Alexander II in 1881 inaugurated a combination of pogroms (mob violence against the Jews) and anti-Semitic May Laws, which limited every aspect of Jewish life in the Russian Empire. For the following 40 years, the increasingly difficult living conditions for Jews, coupled with wars and revolutions, set in motion a population shift that would affect not only the Jewish communities of Russia and Eastern Europe but also the United States.

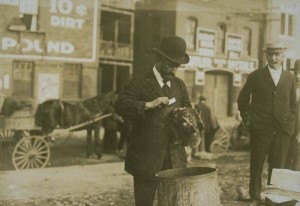

Rabbi about to bleed chicken, Hartford, 1912 – Connecticut Historical Society

By 1910, the Jewish population in Hartford had increased to about 6,500. Despite their lack of money, education, and sophisticated economic skills, the Eastern European newcomers brought a religious tradition of a strong, supportive community. The number of synagogues and other religious institutions, political organizations, landsmanschaften (organizations based on hometowns in Europe), mutual aid societies, cultural clubs, educational programs, Zionist organizations (groups advocating the founding of a Jewish homeland on the site of the Biblical Holy Land), and burial societies multiplied. Members took on the responsibility of caring for each other and for their less fortunate relatives overseas. In 1912, 30 diverse groups—including those founded by the German Jews—organized into a single charitable association, the United Jewish Charities, the forerunner of the current Jewish Federation of Greater Hartford, established in 1945.

In 1918, following the flu epidemic of that year, a group of Jewish doctors and community members met to discuss the need for a Jewish hospital. Five years later Mt. Sinai Hospital opened, providing a place where Jewish patients would be comfortable and where Jewish doctors—who were often refused positions at the Protestant Hartford Hospital or the Catholic St. Francis Hospital—could practice.

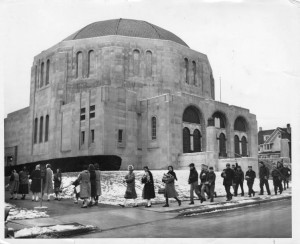

Temple Beth Israel Synagogue, West Hartford, 1957 – Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

The Areas of Second Settlement

By the 1920s, the wealthier German Jews had already left the immigrant neighborhoods, with a few moving farther south toward Beth Israel Temple, which had been erected in 1876, on Charter Oak Avenue. This was the first structure in Connecticut to be built specifically as a synagogue. Others scattered throughout the western part of the city, particularly to the West End, and to the large homes on both sides of the West Hartford line.

Although some Eastern European Jews relocated to areas of the city near their businesses, the majority began to move north and west toward Garden Street and beyond. Albany and Blue Hills Avenues and Keney Park became the heart of the area of second settlement with the synagogues, businesses, Jewish communal organizations, and cultural groups following their members to the new neighborhoods.

Depression and WWII

In the 1930s, the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany led to new concerns: the rescue and resettlement of the German Jews. With the Immigration Restriction Acts of the 1920s seriously limiting the flow of refugees into the United States, many Jews began to look to the establishment of a Jewish homeland. Despite the fact that few Hartford Jews were wealthy and that the country was in the midst of a Depression, many contributed heavily to fund-raising campaigns, attended rallies and lobbied in Washington for refugee relief. Both before and after the war, Hartford Jews fought to bring in the refugees, many of whom were members of their own families.

World War II hit Hartford’s Jews on two fronts: first as Americans with 55 Hartford men killed while serving in the armed services and second as Jews, worrying about family and friends in Europe. It was not until the liberation of Auschwitz in 1945 that the enormity of the Nazis’ Final Solution for the Jews began to become common knowledge. The question of what should be done with the survivors seemed insoluble with the British refusing to admit them into Palestine. Clearly, it was critical for the Jewish relief agencies to raise large amounts of money rapidly, and Hartford, under the auspices of the Jewish Welfare Board, rose to this task.

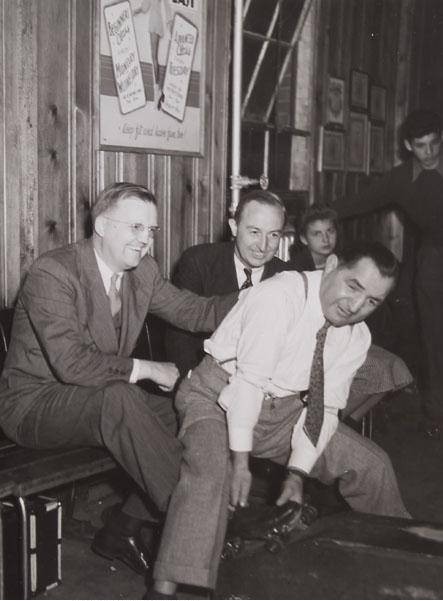

Louis “Kid” Kaplan and William H. Mortensen, ca. 1943. Kaplan was a Russian born boxer who settled in Hartford and became the world featherweight champion in 1925-26 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Illustrated

The Move to the Suburbs

Although some Jewish families had left the North End for the suburbs in the 1930s, the true exodus did not begin until after the war. As part of a national trend toward mixing with members of other white ethnic groups, young second and third generation Americans—Jews among them—who had attended public schools, spoke unaccented English and had served in the armed forces, were looking beyond their former inner city neighborhoods. Many used their government benefits for higher education, which would increase their earning potential and allow them to buy new homes in the suburbs.

Just as had happened in the past, as the Jewish population moved from one neighborhood to another, the institutions—synagogues, social service agencies, clubs, and recreational facilities—followed them, in this case, primarily to West Hartford.

By the end of the 20th century, few Jews remained in the city of Hartford. In 1989, the same year that the Hebrew Home, a healthcare organization for older adults, left the city for its new facility in West Hartford, Mt. Sinai Hospital, which had served the needs of both the Jewish community and the larger neighborhood for more than 70 years, negotiated an alliance with St. Francis Hospital and Medical Center. With the merger complete in 1995, Mt. Sinai, the last of the Jewish institutions in the city, ceased to operate under Jewish auspices. However, the Greater Hartford Jewish community, estimated to be about 32,000 in 2012, has flourished with synagogues, schools, social service agencies, and the Jewish Federation of Greater Hartford maintaining a strong presence in the suburbs.

Betty N. Hoffman, PhD, is an anthropologist/oral historian specializing in the study of Jewish life in Connecticut. Her books are available through the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford.