By Walter W. Woodward for Connecticut Explored

For most Connecticans, the War of 1812 was as much a war mounted by the federal government against New England as it was a conflict with Great Britain. More precisely, they saw it as a politically based and profoundly unconstitutional military campaign waged by the Jeffersonian Republican party (which dominated the South, the West, and the national government) against the Federalist-controlled states of New England. They saw it as unconstitutional war of aggression, rather than one waged for defense. They also felt it ran counter to the values, morals, political beliefs, and economic and security interests of the north. For these reasons, in a state that has found much to oppose in many of America’s military campaigns, the War of 1812 remains by far the most hated conflict in Connecticut’s history.

US Political Divisions Shape Responses to New European War

The roots of Connecticut’s disdain for the war stretched back almost a generation, to the very founding of the country and the rise of America’s first political parties. The vast majority of Americans had opposed the idea of political parties as inherently dangerous to the new American republic, because they would promote self-serving political behavior rather than disinterested public service. The very act of ratifying the United States Constitution and forming a government had, however, produced political parties with very different views of what was in the national interest. The Federalist Party, centered in New England and led by John Adams, believed in a strong national government and looked to reestablishing close ties with Great Britain as the best way to promote rapid American economic development and international trade.

The Republican Party, centered in the agrarian South and the new Western states and led by Thomas Jefferson, feared states could lose too much influence to the new national government and sought to limit its growth and relative power. Jeffersonian Republicans deeply mistrusted England (and its supporters) as the “former enemy” and looked to France, especially after its republican revolution in 1789, as America’s natural ally. These opposing views on domestic policy and international relations put the two parties on a collision course whose ultimate test would be the “Second War for Independence” in 1812.

While Connecticut Federalists played important roles in, and were generally pleased with, national government policies under the Federalist presidencies of George Washington and John Adams (1789-1800), the state’s standing order was far less pleased with the Republican administrations of Jefferson and Madison (1800-1817). Each party came to see the other as engaged in a conspiracy to destroy its political opponents. Jeffersonians had railed against the Adams administration’s efforts to suppress dissent through the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. Similarly, Connecticut Federalists viewed Jefferson’s 1803 Louisiana Purchase as an unconstitutional attempt to marginalize New England by creating new states to dilute the North’s national political power and increase the already problematic out-migration of Connecticut’s rising generation.

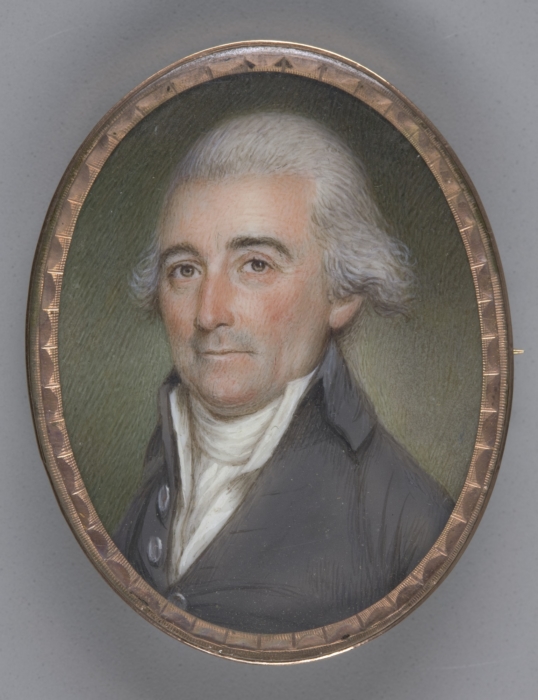

James Peale, Jonathan Trumbull, Jr., ca. 1792, Watercolor on ivory – Yale University Art Gallery

Independent Connecticut Refuses to Follow Federal Orders

New Englanders’ harshest criticism, however, was reserved for Jefferson’s response to the increasing assaults on American shipping by both Britain and France. At the time, Britain and France were deeply engaged in the Napoleonic wars. In an attempt to retaliate against both countries by preventing them from getting much-needed American-made goods, Jefferson pushed the Embargo Act of 1807 through Congress. It prohibited international trade at all American ports, which wreaked particular economic havoc in a New England long dependent on shipbuilding and ocean commerce. When the Republican Secretary of War Henry Dearborn ordered Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull to deploy the state militia to enforce the embargo, the governor simply refused. Instead, he called a special session of the Connecticut General Assembly “to interpose their protective shield between the rights and liberties of the people and the assumed powers of the Central Government.” Connecticut thus became the first state to use a claim of states’ rights to refuse to implement a federal law. As far as Connecticut was concerned, historian Jack Chatfield notes [in his introduction to The Public Records of the State of Connecticut 1812-1813 vol. XVI (Hartford, Office of the State Historian, 1997)], “the President and his followers were little more than blind followers of Napoleonic France and the inveterate foes of New England commercial interests.”

When Congress (without a single Federalist vote in favor) declared war on Britain in June 1812, Connecticut’s political leaders were incensed. They expressed unrestrained outrage at President Madison’s call for war and his strategy to win the war by using state militia forces to seize Canada from the British. When Connecticut was ordered to detach its militia for the federal campaign, it flatly refused. A special session of the General Assembly condemned both the war and the federal effort to mobilize the state’s militia as unconstitutional. “It must not be forgotten that . . . Connecticut is a FREE, SOVEREIGN, and INDEPENDENT State; [and] that the United States are a confederacy of states . . . . The same constitution, which delegates powers to the General Government, inhibits the powers not delegated, and reserves those powers to the States respectively.”

The war did not go well for the United States, and as the military campaign to take Canada stumbled again and again, Connecticut Federalists publicly ridiculed the military’s fumbling efforts with a mixture of anger and delight. (At the same time, they attributed the American naval successes—the only bright spot in the war—to New England’s shipbuilding prowess and Yankee captains’ courage.) The botched invasion of Canada, it seemed to many, was little less than a Republican invitation to the British to take revenge on New England, Canada’s immediate neighbor to the south and the region that most opposed the conflict.

Talk of Secession from Union

A movement began among the most radical Federalist opponents of the war to form a New England confederation and secede from the union. “That the present dynasty and their measures will eventually produce a separation of the States,” reported The Connecticut Mirror on February 8, 1813, “is much to be apprehended.” As the war dragged on, the confederation movement grew, though it never represented the dominant sentiment of the state’s political leadership. The majority’s position was that the war was unconstitutional and the administration that prompted it vile and reprehensible, but the Constitution, and the Union it formed, were still worthy of loyalty.

The infamous British blockade of New London in December 1813 that kept US Navy Captain Stephen Decatur’s three-boat squadron stuck up the Thames River for months cast a shadow on the war’s most radical opponents. It seems that unknown persons warned the British of Decatur’s attempted escape by placing blue signal lights on the heights of both New London and Groton. Were the warning lights set by Loyalists or by disgruntled Connecticut Federalists? Republican critics later repeatedly denounced the actions of the supposed “Blue Light Federalists” as treasonous. At the time, though, even the Federalist New London Gazette called the signals the work of “traitorous wretches” (December 15, 1813).

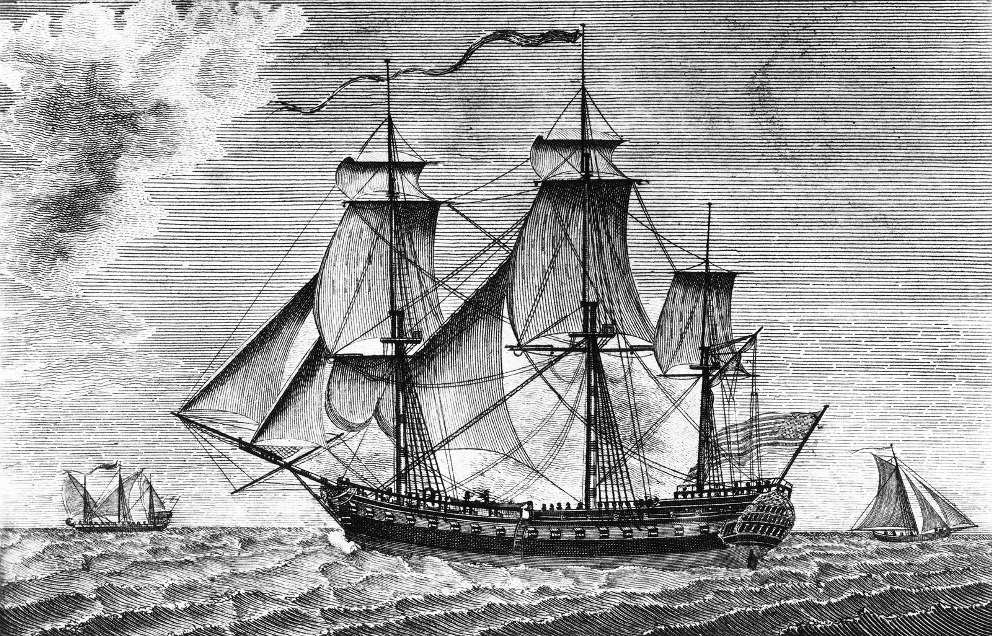

The naval frigate USS United States commanded by Captain Stephen Decatur in the War of 1812 by T. Clarke in American Universal Magazine, 1797 – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Connecticut’s leadership was again embarrassed four months later. At 4:00 a.m. on April 8, 1814, British soldiers disembarked at today’s Essex, where they torched or took more than two dozen ships. Though caught off guard, the militia were rallied from other towns in time to kill two British and injure one as the British soldiers rowed back to the safety of ships waiting to pick them up. Although Connecticut’s leaders tried to pin the blame on the federal government’s failure to provide the state protection, their Republican opponents placed the blame squarely on the state’s own failure to deploy its militia.

Britain, buoyed by its recent victories over the French and by Napoleon’s abdication, approached the American conflict with renewed vigor and increased resources in summer 1814. They decided to blockade the entire New England coast and crush the region’s commerce. Their attack on Stonington in August, ably defended by a shoreline battery backed up by three regiments of state militia, was a key moment in the conflict and represents the anti-war state’s most patriotic hours.

The British blockade was proof to the Federalists that Madison, in an effort to win the war in the West and South, had left New England completely undefended. Combined with the success of the British campaign in the Chesapeake and the August burning of the nation’s capital, its effect was to embolden those New Englanders who sought to form a new confederation. In September, the Massachusetts legislature called for a convention of New England states to meet in Hartford in December to plan a coordinated defense of New England and correct “defects” in the national Constitution. A worried Secretary of War James Monroe sent two Army regiments on recruiting duty in Connecticut and transferred other units to New York (near Albany). Should any move be made at the Convention to “disrupt the Union,” Colonel Thomas Jessup was to seize the Springfield armory. Yet during the Convention, the Connecticut delegates took a conservative stance; largely through their efforts, the final report was relatively temperate.

Subsequent and surprising events—Andrew Jackson’s victory at New Orleans and the news of the Treaty of Ghent that ended the war—discredited the Hartford Convention so thoroughly, however, that the convention’s report was dead on arrival in Washington. Later Republican “spin” on the convention as treasonous and unpatriotic would help destroy the Federalist Party nationally and set the stage for overturning Connecticut’s Standing Order and creating the state’s Constitution of 1818. This patriotic backlash after a surprise “victory” should not obscure the fact that the War of 1812 was, from beginning to end, the most hated war in Connecticut’s history.

Walter Woodward is the Connecticut State Historian

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal ) Vol. 10/ No. 3, Summer 2012.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.