By Nancy Finlay

“The mass is changing. We are becoming another people,” Congregationalist minister Lyman Beecher proclaimed in the second decade of the 19th century. The changing demographics to which Beecher referred were not a matter of race or ethnicity and they were not the result of an influx of immigrants from outside Great Britain. That wave was yet to come. The great change that Beecher (and many others) lamented was due to the decline of the Congregational Church and the rise of other competing Protestant sects.

Although only a minority of Connecticut’s population was Congregationalist in the second decade of the 19th century, the Congregationalists remained in control of the state government and the Congregational Church still dominated most aspects of civic life. Only a very small percentage of eligible voters turned out to vote in Connecticut’s frequent elections, and they continued to support the Federalist Party, the party of the Standing Order and the Congregationalists. Newspapers such as the Hartford Courant promoted Federalist ideals, teachers taught Federalist propaganda in the classroom, and preachers extolled Federalism and the status quo from their pulpits. Feelings ran high as the Federalists sought to maintain their insider status and their traditions, while their opponents struggled to obtain equal rights. Lyman Beecher denounced this opposition, calling its proponents “infidels” and “enemies of truth.”

Federalists and Republicans in Connecticut

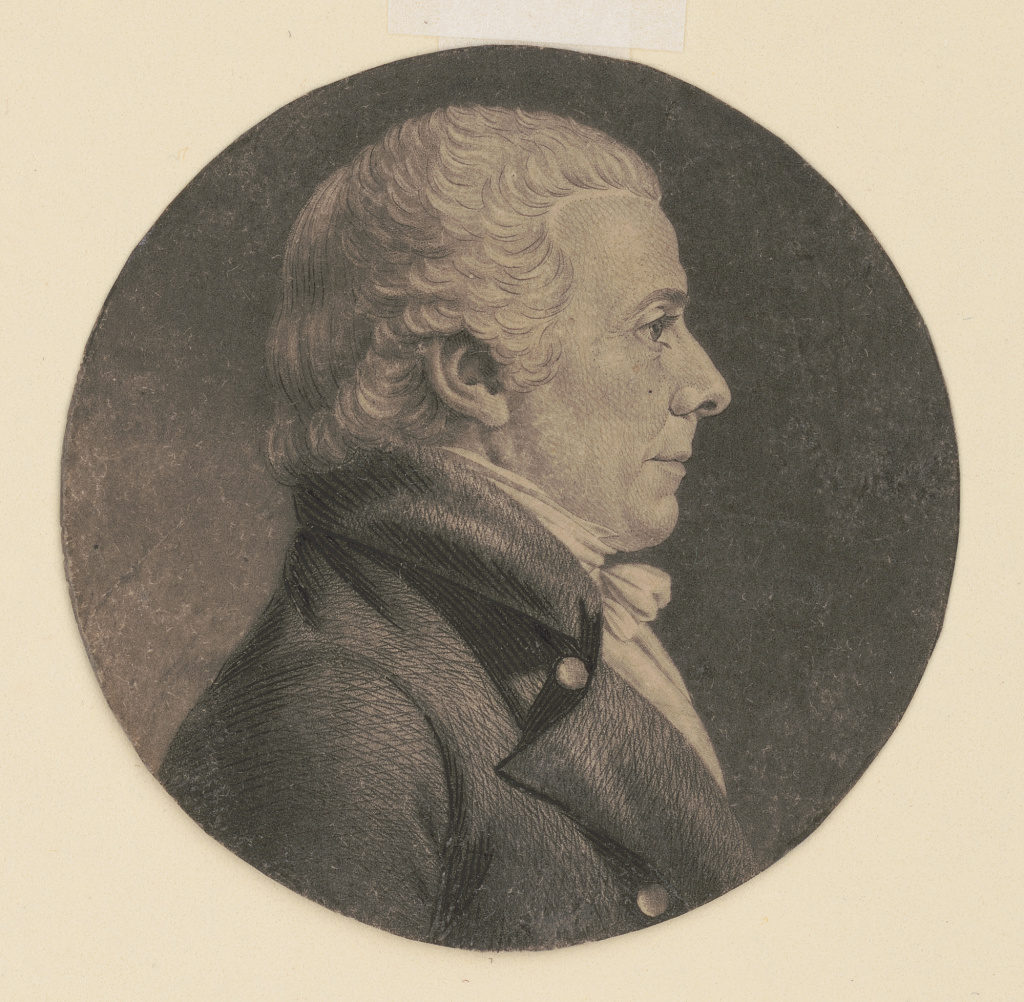

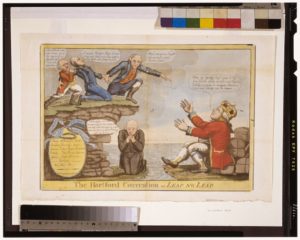

William Charles, The Hartford Convention or Leap no Leap, ca. 1814, etching and aquatint with watercolor – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

This struggle for equal rights began in earnest shortly after 1800, when Thomas Jefferson became president of the United States. Jefferson’s supporters constituted the new, more liberal Republican party, denounced by the Federalists as radicals and atheists. The men that Jefferson appointed to government positions in Connecticut—tax collectors, postmasters, and judges—formed the core of the Republican party in Connecticut, which began to gain a limited voice in the affairs of the state. Most Connecticut Republicans in these early years were either Baptists or Methodists or members of smaller religious sects. These Republicans organized large “festivals” and “celebrations”—the first political rallies—to arouse support for their candidates.

John Cotton Smith, a “strict old Puritan,” became governor of Connecticut in 1814. During these troubled times, the Federalists opposed the Embargo Act of 1807 and the War of 1812. Leading Connecticut Federalists played a prominent role in the Hartford Convention of 1814 at which representatives of the New England states met to discuss their grievances with the national government. Some delegates went so far as to suggest that New England secede from the Union.

When the war ended early in 1815, the Federalists found themselves widely discredited and considered subversive and treasonous. Connecticut’s Republicans castigated them as traitors and advocates of disunion. Even many long-time Federalists became disillusioned with their leaders.

The Toleration Party

Toleration Ticket. The honorable Oliver Wolcott for governor. And the honorable Jonathan Ingersoll, for lieut. Governor – Connecticut Digital Archive

In February 1816, a statewide convention of anti-Federalists took place in New Haven, resulting in the formation of the Toleration Party. The new party’s members included many Episcopalians, who formerly supported the Federalists, but now allied themselves with the Republicans. They nominated Oliver Wolcott Jr. (a former Federalist and a Congregationalist) for governor, and nominated Jonathan Ingersoll (a Republican and an Episcopalian) for lieutenant governor. In April 1817, following a vicious and hard-fought campaign, the Toleration Party defeated the Federalists, ousting incumbent John Cotton Smith, and taking control of the state General Assembly.

For Federalists, their defeat meant the end of their party as an effective political force and the end of the old order that they fought so hard to maintain. One old Federalist later wrote, “In the great revolution which followed the retirement of Governor Smith . . . Connecticut abdicated her Christian standing. The ancient spirit which had shaped her institutions and linked her, in her corporate capacity, to the throne of the Almighty for almost two hundred years, was then expelled, and the State ceased henceforth to wield power as a religious Trust. New and alien principles obtained the ascendancy, and the divine life, imbreathed into the Commonwealth by its godly founders, was no longer the controlling law.” But Republicans rejoiced the triumph of democracy and the beginning of more representative government in the state.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.