By Elizabeth Correia

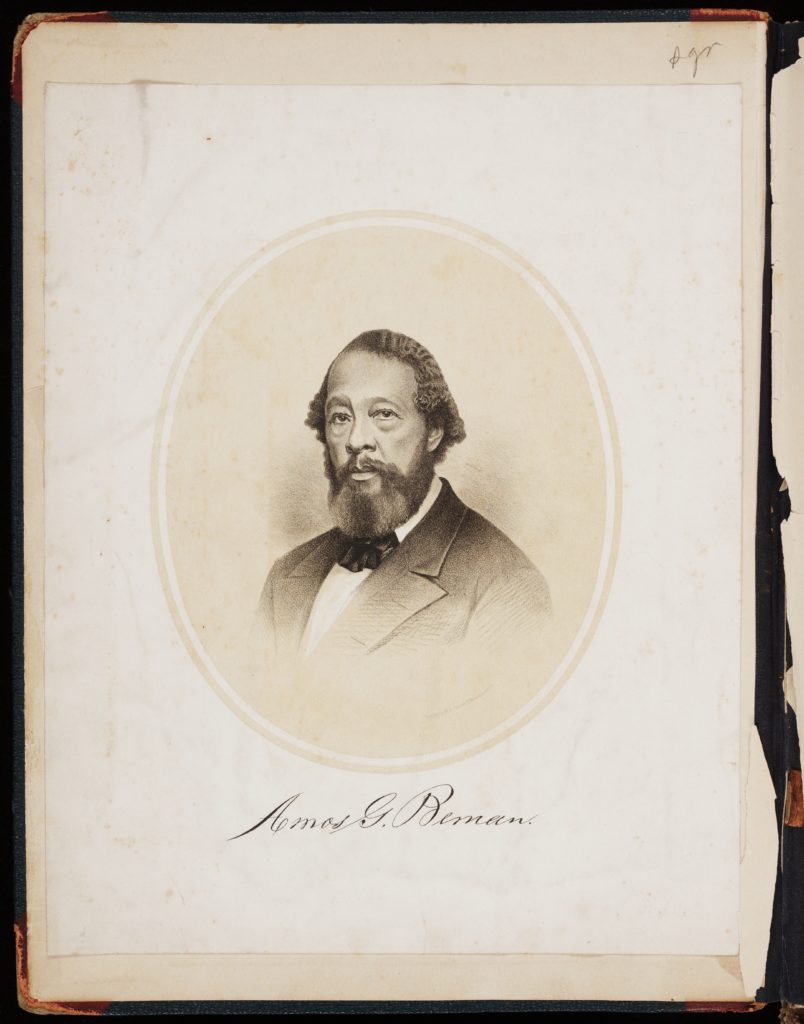

Amos Beman spent much of his life a religious leader and social activist in New Haven. After Wesleyan University administrators blocked him from studying at the school because of his race, Beman went on to enroll at the progressive Oneida Institute, using what he learned to write and speak on the liberation of the oppressed. Beman’s interracial marriage in 1857 ostracized him from the Black congregation he served in New Haven, but he remained tied to the city until his death.

Education and Obstacles

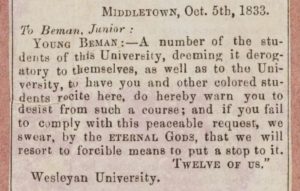

A copy of the letter warning Beman not to enroll at Wesleyan, as printed in Frederick Douglass’ Paper. Source: Amos Beman Scrapbooks v. II, pg. 92. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the American Literature Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Amos Gerry Beman was born in 1812 to Jehiel and Fannie Condol Beman of Colchester, Connecticut, the second of five children. In 1830 the family moved to Middletown, the year Jehiel became pastor of the Cross Street AME Zion Church there. Amos took advantage of his new proximity to Wesleyan University to apply for classes but the school board of trustees blocked his admission, not willing to allow a Black student into the university. Undeterred, Amos took lessons from a Wesleyan student until 1833, when he received the following letter signed “TWELVE OF US. Wesleyan University”:

Young Beman:–A number of the students of this University, deeming it derogatory to themselves, as well as to the University, to have you and other colored students recite here, do hereby warn you to desist from such a course; and if you fail to comply with this peaceable request, we swear, by the ETERNAL GODS, that we will resort to forcible means to put a stop to it.

Amos subsequently left Middletown for Hartford, where the City of Hartford officially certified him to teach a district school for Black children in 1833. While working, he heard news of the Oneida Institute’s new progressive education programs. He enrolled at this New York institute in 1835 alongside Black and white classmates. Here, Beman studied mathematics, astronomy, chemistry, theology, philosophy, and Hebrew poetry, among other courses, for four years—coursework that assuredly put him on the path to becoming a pastor, like his father.

Pastorate and Advocacy

A view of Temple Street in New Haven in 1880. Source: Connecticut Images Collection, Connecticut Historical Society. http://hdl.handle.net/11134/40002:13554.

Amos Beman’s first placement was at the Temple Street Congregational Church (now Dixwell Avenue Congregational) in New Haven in 1837 where he eventually became pastor. Membership grew under his leadership and calls for the construction of a new church soon followed. Beman worked unpaid for years until the funds were raised for the new building. When it was completed in 1845, Beman used the church to host Black activist speakers, organize classes on motherhood, operate a school, and at times house fugitives on the Underground Railroad.

Amos Beman also lectured across the United States and wrote for many Black newspapers (opposing slavery, colonization, and the lack of education opportunities for the Black community) but was most vocal about the Temperance Movement. Beman served as president of the Connecticut State Temperance and Moral Reform Society of Colored People, founded by his father. He convinced many men to pledge total abstinence from all intoxicating liquors, fearful that alcohol led Black men to suffer high rates of depression, disease, unemployment, and death, as well as receive unfair criticism from whites about supposed alcoholic tendencies. Despite it all, Beman knew, as he stated during an 1839 address in Hartford, that “the day will come, when we shall stand on an elevated position in society . . . when the hearts of the people will flow together, and be cemented in love, when the unhappy influences and false principles will be banished.”

In 1856, typhoid fever took Beman’s wife, Eunice, and two of their five children. The pastor remarried in 1857 after falling in love with Eliza Kennedy—a match that shocked his congregation members because Eliza was white. Ultimately, the backlash Amos received for his union with Eliza forced him to resign as pastor of Temple Street. He went on to serve short-term positions at churches in Maine, New York, Ohio, Indiana, and Massachusetts and performed missionary work in New England and Tennessee. All the while he kept a residence on Howe Street in New Haven, never completely disconnecting from the city. He returned for social events, even presiding over Jubilee, celebrating the emancipation of enslaved people in the District of Columbia. Eliza passed away from cancer in 1864 and Amos married a Black woman named Mary Allen in 1871. Amos Beman died just three years later, on June 29, 1874, and received a burial in Evergreen Cemetery in New Haven.

Elizabeth Correia holds a MA degree in Public History from Central Connecticut State University and works in cultural resource management.