With its abundant waterways, Connecticut, like the rest of New England, had the necessary power source to fuel a revolution in manufacturing that, together with other innovations of the late 1700s and early 1800s, led to sweeping transformations in the United States.

Slater Introduces British Manufacturing Practices to US

The Industrial Revolution describes a roughly 100-year period in which mechanization led to changes in agriculture, transportation, manufacturing, and technology. Beginning in Great Britain around 1760, these forces brought profound alterations to the social, economic, and cultural conditions of the age.

The Industrial Revolution in the United States began in earnest with the formation of textile mills along the waterways of the towns of New England. Samuel Slater, an Englishman with experience in the mills of his native country, came to the US in 1789 and helped establish the nation’s first cotton mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Throughout his lifetime, Slater founded mills in Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts.

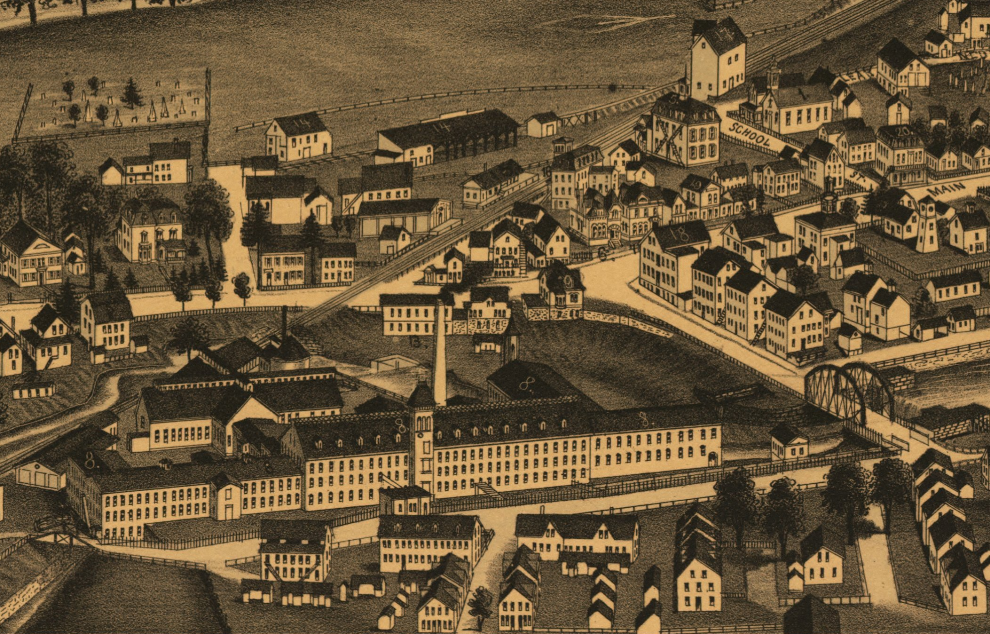

Slater’s 1823 expansion into Connecticut was paved by an earlier venture. In 1809 two Rhode Islanders, John and Lafayette Tibbits, bought property in Jewett City. (Today, Jewett City is a borough of Griswold.) Sitting along the confluence of the Pachaug and Quinebaug rivers, Jewett City had earlier been the site of corn, grist, and saw mills, so the spot seemed well-suited to the Tibbets’ textile enterprise: the Jewett City Cotton Manufacturing Company. However, the firm struggled for years before it was sold in 1823 to Samuel Slater and his brother John, who had joined Samuel in the US. They soon changed the name of the mill to Slater Company. In the years that followed, John and his son, John Fox Slater, introduced mechanical improvements to increase production. They also expanded operations to include another mill in nearby Hopeville.

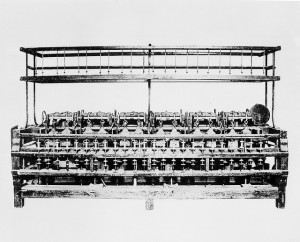

The oldest piece of cotton machinery in America the 48-spindle spinning machine built by Samuel Slater, ca. 1790

Surviving records from the early years of the Slater Company in Connecticut reveal much about the nature of day-to-day mill operations, including insights into relations between management and labor. As workers shifted from being small producers of hand-made materials to being paid laborers in increasingly mechanized factories, frictions inevitably arose when the interests of employers and employees diverged. For example, a letter written by Samuel Slater in 1823 advises Ezra W. Fletcher, a supervisor of the Jewett City property, on how to deal with workers who had objected when asked to increase their workloads. The workers in question were known as spinners because they monitored spinning machines whose sides consisted of long banks of fast-moving spindles (tapered rods around which yarn or thread is wound) to ensure threads did not break, entangle, or otherwise slow down production. Slater issued the following instructions:

As respects the spinners, who refuse to tend more than two sides, … case them down as soon as it can be legally done, all my spinners at Oxford, [Massachusetts,] tend four sides of 128 spindles.

This single line reveals management’s expectations that a single worker could manage four banks, or sides, rather than two. In practical terms, by doubling the spinners’ work the factory could either employ fewer spinners or expand the number of spinning machines without a corresponding increase in labor. This letter provides a glimpse into the human struggle being waged in factories across New England as the Industrial Revolution transformed the nature of work.

Contributed by Laura Smith, Curator for Business, Railroad, and Labor Collections, Archives & Special Collections, University of Connecticut Libraries.