Thursday July 6, 1944, was a miserably hot day in Connecticut. In a field on Barbour Street in Hartford, between six- and eight-thousand patrons sought distraction from the summer heat by attending a performance of the Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus. A matinee show featuring trapeze artists, clowns, and animal trainers drew customers into the roughly 500-foot-long big top. No one had any idea they were about to play a part in one of the worst disasters in Connecticut history.

Following a performance by the French lion tamer, Alfred Court, famous trapeze artists, the Great Wallendas, took their positions inside the big top and began their routine. Meanwhile, just outside the tent (as the widely accepted story theorizes), a carelessly tossed cigarette near the partition to the men’s toilet started a small fire. The fire, once in contact with the tent canvas, rapidly spread, due largely to the waterproofing of the canvas through the application of paraffin wax thinned with gasoline.

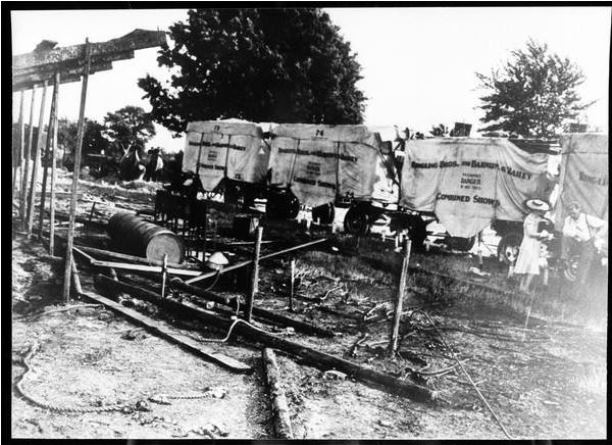

Circus carts site beside the burned stands, July 1944 Hartford Courant file image

One of the performers noticed the fire and screamed, “The tent’s on fire!” Bandleader Merle Evans quickly had his musicians break into “Stars and Stripes Forever,” a predetermined signal to circus employees that something was horribly wrong.

As the flames reached 100 feet high, panicked patrons ran for the exits, only to find several of them blocked by animal cages in the process of being moved in and out of the tent. Bottlenecks formed at the exits as patches of burning canvas began raining down on circus attendees. Those unable to escape through the designed exits began slashing holes through the canvas to make their own way out.

Ushers and other circus personnel ran toward the flames with buckets of water, but they were too late. In less than 10 minutes the fire burned through poles and support ropes sending the remnants of the 19-ton big top crashing down on those not fortunate enough to have already escaped.

Little Miss 1565 and Others Remembered in Hartford Circus Fire Memorial

By the time firefighters put out the flames, nearly 170 people lay dead. Most died from exposure to the fire and smoke, but a significant number were also trampled. Perhaps the most famous victim of the fire was a little girl without a name. Known as Little Miss 1565 (a name derived from the number assigned to her at the city morgue) debate about her identity remains to this day. Some believe her to be a local six year old named Sarah Graham, while others theorize she is Eleanor Emily Cook, a young girl from Massachusetts.

Clown with bucket, Hartford Circus Fire, 1944 – Connecticut Historical Society

Authorities deemed the fire a terrible accident (most likely caused by a carelessly tossed cigarette) and never charged anyone with starting it, but this did not exonerate Ringling Brothers officials from some form of culpability. Four men faced charges for acts of negligence. Sited among these acts was a lack of fire preparation on the part of circus management. An investigation into the blaze revealed that at the time of the performance, the circus’s fire extinguishers remained buried and inaccessible in a storage unit, while its fire trucks rested more than a quarter-mile away. Investigators also charged the circus with failing to notify the Hartford Fire Department of their arrival and intention to perform.

In the end, the four circus officials pleaded no contest to the charges and spent approximately one year in prison before eventually receiving pardons. In addition, the circus agreed to pay nearly $5 million in compensation to the families of the victims.

An interesting twist to the story came six years later. Police in Ohio arrested Robert Dale Segee for starting a number of fires in 1950. Under intense interrogation, Segee, a former circus employee who worked at the 1944 performance in Hartford, confessed to starting the fire, along with fires in Maine and New Hampshire and even to committing four murders. Authorities committed Segee (who claimed the figure of a ghostly Native American riding a flaming horse told him to start fires) to the state hospital for treatment of paranoid schizophrenia. Years later, Segee recanted his confession.

As a result of the Hartford Circus Fire of 1944, Connecticut enacted new, strict fire safety regulations for public performances. In July of 2005, the site of the 1944 fire, now a small field behind the Wish School in Hartford, witnessed the dedication of a memorial to the victims of that day’s tragic events.