By Steve Thornton

The steamship Hero made its way up the Connecticut River. It was October 1, 1850; two men with different purposes traveled aboard the vessel. The first was a runaway slave, now working on the steamer. The second was the fugitive’s owner, determined to get him back. Waiting on the Hartford docks were slave catchers, ready to help the owner when the ship reached port.

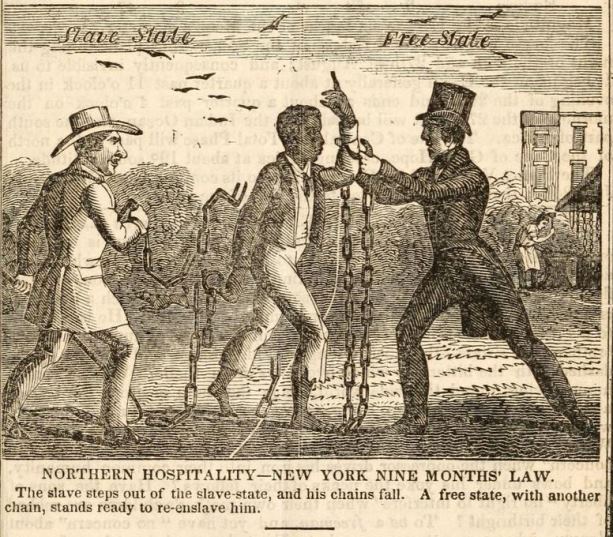

Slave hunting was a profitable business. The U.S. Constitution specifically required the return of escaped “persons held to service or labor.” The government passed two laws to enforce this provision. The first passed in 1793, and the second was the infamous Fugitive Slave Act. This act was part of the Compromise of 1850, a desperate legislative measure meant to keep the country together. Brokered by northern politicians, the “compromise” permitted slavery to exist in some new states and gave vigorous federal support to slave owners who demanded the return of their property.

Detail from a news article in the Times “The Fugitive Slave Meeting”, October 12, 1850, Hartford, Connecticut

Approved less than a month before the Hero traveled up river, the Fugitive Slave Act required local officials in every state to assist in the capture of runaways and allowed them to get paid for their efforts. Anyone who did not help–or worse, actually aided a fugitive–faced fines and imprisonment. In addition, the alleged slave had no legal right to protest his or her capture. The word of an aggrieved owner in court was enough.

A Narrow Escape

A local anti-slavery newspaper took notice of the slave hunters hanging around the Hartford docks just before the Hero arrived. The Republican, published weekly by J.D. Baldwin from his office at 20 State Street (a short walk from the river) taunted the men trying to profit from slavery:

“Slave hunters made their appearance in Hartford…It was noticed that they paid particular attention to the steamer Hero which had just arrived from New York. Nice boat; isn’t she, Messers. Slave Hunters?”

Baldwin called the new slave law “kidnapping made easy.” He wrote that the legislation “delivers every colored person to the mercy of any kidnapper who may see fit to claim him as a ‘fugitive’.”

What the slave catchers did not know was that the hunted man already got off the ship down river, apparently discovering what awaited him in Hartford. He escaped at East Haddam, the home of the Goodspeed shipbuilding enterprise and a center of strong anti-slavery sentiment. (The Hero was built by the Goodspeeds and probably designed by Gideon Higgins, a local abolitionist.) By land, the former steamship worker then made his way along Connecticut’s Underground Railroad. Once safely hidden in Hartford, he met up with four other escaped slaves. All five fugitives then made their way to Canada where, as Baldwin later wrote, “man-stealing is not lawful.”

Steve Thornton has been a labor union organizer for 35 years and writes on the history of working people.

A version of this article originally appeared on ShoeLeatherHistoryProject.com