By Tyler Wolanin

In the early 20th century, when supporters of the New Deal tried to recreate the Tennessee Valley Authority in the Connecticut River Valley, they ran into strong opposition from business interests and cultural conservatives wary of the federal government. Eventually, efforts converged on a voluntary agreement between states; and those politicians who wanted a Connecticut Valley Authority (CVA) found themselves swept away in the political tide that followed a disastrous flood in 1938.

The Tennessee Valley Authority was one of the crown jewels of the New Deal, a massive federal infrastructure project using dams to bring hydropower, flood control, and regional planning to seven southern states. Within a few years of its enactment, New Dealers made plans to enact similar projects in other river valleys. It was to this end that Congressman William Citron introduced the Connecticut Valley Authority bill in 1935.

William Citron was the Representative for Connecticut’s At-Large Congressional District, first elected in 1934. A lawyer and former state representative from Middletown, Citron was also an active member of the Jewish community and a veteran of the First World War. As someone who grew up on the banks of the Connecticut River, he had a longstanding interest in its development and future, and his CVA bill was introduced in the very first days of the session.

An Outgrowth of the TVA

Citron’s bill for a CVA was one of over twenty bills creating new regional authorities introduced in 1935, even as President Roosevelt attempted to tamp down the drive for these projects. Roosevelt told his director of the Bureau of the Budget that there would be no new authorities created that year and told Congressman Citron that before a project could proceed, “it seems to me that there should be a fairly unanimous sentiment in the area affected,” including the need for support in all four states on the Connecticut River.

Sentiment was indeed against the bill in some quarters. The New England Regional Planning Commission (NERPC) voted to reject Citron’s bill; instead expressing support for an interstate compact to develop the river. The NERPC was officially a government body but was also the successor to a business-oriented regional chamber of commerce that organized in the 1920s. In supporting an interstate compact, it took its lead from private power companies, who opposed selling federal hydropower at “public preference” to municipalities or cooperatives rather than at a profit.

Following this vote by the NERPC, Citron set aside his CVA bill and introduced a new bill enabling the New England states to enter into interstate compacts for flood control. The Roosevelt Administration opposed this bill as a preemptive block of any future New Deal development; but the president’s hand was forced when a devastating flood, one of several during the era, hit the entire Connecticut River Basin in March of 1936. Roosevelt signed Citron’s bill in June of that year.

With a flood control compact authorized, the New England states then had to agree to form one. They only did so in 1937, after Citron threatened them with another CVA bill. The compact, agreed to by the governors of the four Connecticut River states would have created the Connecticut Valley Flood Control Commission and built eight dams, mostly on the northern reaches of the river, using funds provided largely by Connecticut and Massachusetts. Congress rejected this plan, however, as Citron and other New Deal supporters voted against it.

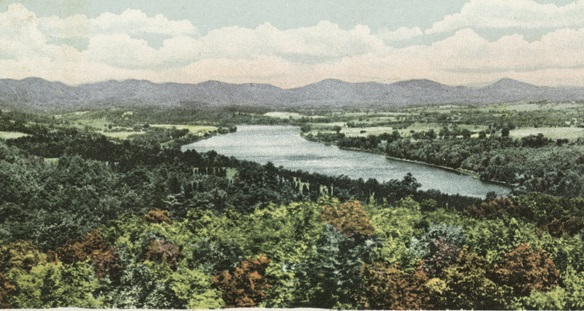

Flooding along the Connecticut River in Middletown, September 22, 1938 – Connecticut Historical Society

This obstinance proved to be their undoing after the river flooded again in September of 1938. Citron and his compatriots, already under fire from power companies, bore the brunt of attacks from their Republican opponents. Citron and three other Connecticut Democratic Congressman lost re-election that year, while two others who had supported the compact were returned.

The events of these years saw the beginning and end of large-scale federal planning on the Connecticut River; a revised Flood Control Act in 1938 allowed the federal government to create only a series of small dams in the river basin, for purposes of flood control. William Citron, despite all of his accomplishments (working on New Deal legislation, his efforts to condemn the Nazi regime and oppose American participation in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, and his legislation to ban lynching) ultimately saw his political fortunes rise and fall with the floodwaters of the Connecticut River.

Tyler Wolanin is a professional legislative drafter and amateur historian, whose blog can be found at tylerwolanin.com.