By Richard DeLuca

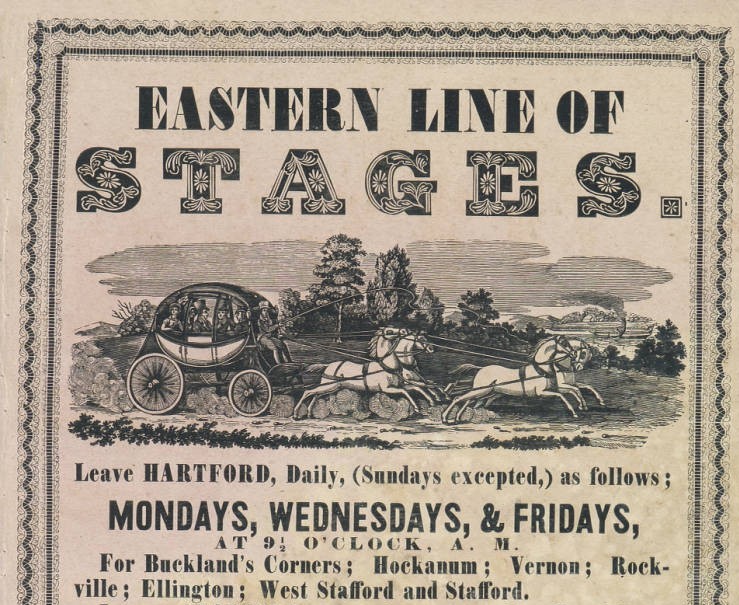

The first stagecoaches appeared briefly in Connecticut in the years immediately preceding the American Revolution. They operated on the Upper Post Road from New York to Boston and from Hartford southeast to Norwich and Providence. Interrupted by the war, stagecoach service resumed in the last decade of the 18th century. Thereafter, it spread rapidly with the proliferation of the turnpike roads that made stage service faster and more reliable. The establishment of numerous local post offices and the expansion of postal service throughout the new nation between 1792 and 1828 also facilitated the spread of stagecoach travel . Indeed, the spread of turnpikes, postal routes, and stagecoach service together created the nation’s first communication network, over which the latest in news and commerce arrived in most every community of any size with the weekly stage.

“the expedition of it all”

Connecticut native and tavern owner from Enfield, Levi Pease established stagecoaching in New England. Pease began his career in 1783 by operating a stage service along the Upper Post Road between New York and Boston. The cost of the service was four pence per mile, with a one-way travel time from New York to Boston of six days. A trip made by Josiah Quincy, President of Harvard College, in 1794 on the line operated by Pease gives a sense of both the adventure and discomfort posed by this early form of public transportation:

Stagecoach, Broad Brook to Hartford, ca. 1875 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

The journey to New York took up a week. The carriages were old and shackling and much of the harness was made of ropes. One pair of horses carried the stage eighteen miles. We generally reached our resting place for the night, if no accident intervened, at ten o’clock and after a frugal supper went to bed with a notice that we should be called at three the next morning, which generally proved to be half past two. Then, whether it snowed or rained, the traveler must rise and make ready by the help of a horn lantern and a farthing candle, and proceed on his way over bad roads, sometimes with a driver showing no doubtful symptoms of drunkenness, which good-hearted passengers never fail to improve at every stopping place by urging upon him another glass of toddy. Thus we traveled eighteen miles a stage, sometimes obliged to get out and help the coachman lift the coach out of a quagmire or rut, and arrived at New York after a week’s hard traveling, wondering at the ease as well as the expedition of it all.

When the United States Congress awarded the mail contract for all of New England to Levi Pease in 1789, he wisely used the steady government income to establish a hub in Boston, from which he expanded his operations into upper New England and westward to Albany. Pease also established an express business, with his stages carrying bundles, bank notes, and other documents—all for a reasonable commission.

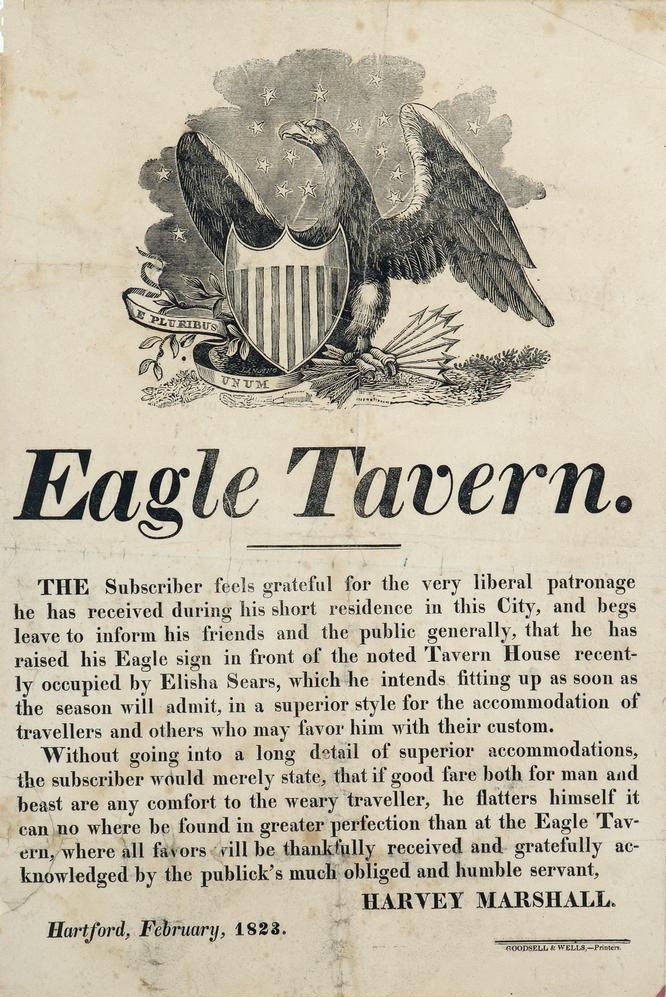

Advertisement for Eagle Tavern, Hartford, 1823 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

As turnpike construction progressed, stagecoach routes within Connecticut multiplied, and other stagecoach proprietors provided passenger and mail service to towns throughout the state. Badger & Porter’s Stage Register of 1827, which contained a listing of routes, fares, and timetables for all New England stages, identified 26 stage routes within and through Connecticut. These included daily service (except Sundays) between Danbury and Norwalk, New Haven and Hartford, and Hartford and Albany and thrice-weekly service to towns such as Litchfield and Middletown. By this time, the one-way stage journey from New York to Boston had been reduced from a bone-rattling six days to a dusty but routine trip of 36 hours.

The locus of stagecoach travel in each Connecticut town was the local tavern, usually run by a man of some standing in the community. Tavern stops were typically 12 to 18 miles apart, and it was not unusual for stage proprietors to have a financial interest in the locations where passengers were to stop for food or to spend the night. Drivers often announced the arrival of their coach by blowing on an English-style trumpet and usually ate their meals with passengers, a custom that class-conscious travelers from abroad were quick to take as a sign of the new nation’s democratic principles.

In its heyday from 1820 and 1840, stagecoaching was a large-scale enterprise and a source of livelihood for a significant number of individuals: proprietors, drivers and ticket agents, coach manufacturers and blacksmiths, tavern owners and stable hands, and the farmers who raised the horses and grew the oats, corn, and hay that kept them running. Stagecoaching was America’s first transportation subculture, the means by which a considerable portion of the nation along the eastern seaboard became readily mobile—and better informed—in the decades before the telegraph, when travel and communication were one and the same. Though the number of stage routes in the state declined with the coming of the railroad, stagecoach service operated in some Connecticut towns into the early 20th century.

Richard DeLuca is the author of Post Roads & Iron Horses: Transportation in Connecticut from Colonial Times to the Age of Steam, published by Wesleyan University Press in 2011.