By Richard DeLuca

At a crucial time in the young nation’s history, when neither national nor state governments could provide funds for construction of roads, state charters allowed groups of investors to purchase shares of stock in turnpike corporations. In exchange for building and maintaining turnpikes with private funds, the turnpike company could charge travelers a toll for the use of its facility and thereby make a profit for its shareholders. This model of a privately owned stock corporation, chartered and regulated by the state government, was first used for turnpikes and toll bridges and would soon be applied to other transportation modes, including canals and railroads.

“In Almost Every Other Direction a Turnpike-road”

Between 1792 and 1839, Connecticut chartered about 100 private turnpike corporations and, collectively, these turnpike companies constructed a network of 1,600 miles of toll roads throughout the state. This amounted to more than 40% of all turnpike mileage in New England. Competition among the many commercial centers and port cities in Connecticut was one reason that so small a state was eventually covered with an extensive web of toll highways. As early as 1807, a visitor to the state, Edward Augustus Kendall, found in Middlesex County, “as in almost every other direction a turnpike-road; for these roads being here made objects of private gain . . . they are established with avidity, on the smallest prospect of advantage.”

The typical Connecticut turnpike, seen in cross section, was a simple design: a convex earthen roadbed, crowned at the centerline and sloped toward drainage ditches that ran along both sides of the roadway.

While some turnpike building consisted of little more than an upgrade to an existing roadway, other turnpikes were constructed, in whole or in part, on a new alignment. This often required cutting a path through wooded areas, leveling hills, and filling in boggy marsh lands—all of which workmen accomplished using little more than an ox-drawn cart or wagon and picks, shovels, and hoes crafted by the local blacksmith. Other construction equipment included a flattened metal disk called a “one-horse shoe” on which large rocks could be hauled away; an ox-drawn scraper to smooth the dirt surface of the roadway; and a plow to dig out drainage gutters along the roadway’s edges.

Few Toll Roads Made Money

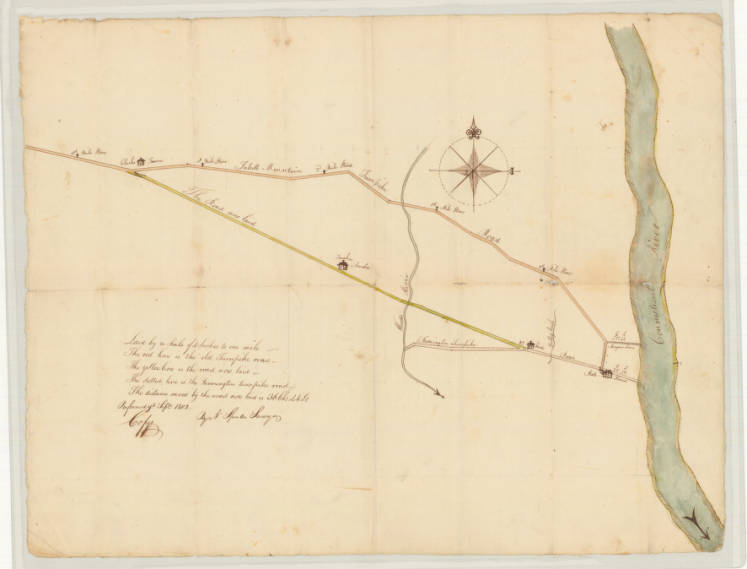

The financial success of individual Connecticut turnpikes varied greatly, depending on the volume of traffic and the availability of nearby public roads that travelers could use to avoid a particular turnpike or toll gate. Only 20 of the 100 operating turnpikes in Connecticut during the 19th century showed profits ranging from 3-10% for 10 years or longer. One exceptional road, chartered in 1798, formed part of the heavily traveled route to Albany, New York, and so the Talcott Mountain Turnpike from Hartford to Avon earned an average profit of nearly 11% for 4 decades running in the first half of the 19th century. But such success was rare, and tempered by the four in five turnpike companies that operated with little or no return on their investment. Many individual turnpike corporations found themselves unable to maintain their routes as required by their charters due to low revenues, so their roadways were returned to public ownership and toll-free travel. The toll gate of Connecticut’s last privately owned turnpike was removed on February 9, 1897.

Overall, the impact of toll roads on Connecticut during the 19th century was a positive one. These privately constructed highways provided for the surge of overland travel, including regular stagecoach service, and made possible the growth of trade and commerce within Connecticut and beyond. At a crucial point in the state’s history, with no assistance from state or national government, merchants, bankers, and other local businessmen took the risk necessary to provide the highways along which Connecticut commerce could thrive. And because many turnpike investors were businessmen in their communities, those who did not profit directly from their financial investment very probably benefited through the trade and business opportunities that their turnpikes made possible.

Richard DeLuca is the author of Post Roads & Iron Horses: Transportation in Connecticut From Colonial Times to the Age of Steam, published by Wesleyan University Press, 2011.